Shaking Ground

advertisement

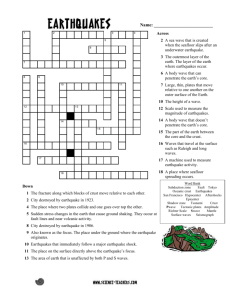

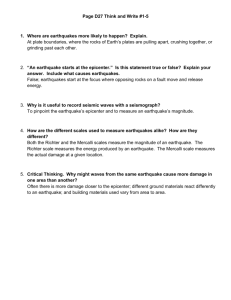

EARTHQUAKES An earthquake is a vibration that travels through the earth's crust. Technically, a large truck that rumbles down the street is causing a mini-earthquake, if you feel your house shaking as it goes by, but we tend to think of earthquakes as events that affect a fairly large area, such as an entire city. All kinds of things can cause earthquakes: volcanic eruptions meteor impacts underground explosions (an underground nuclear test, for example) collapsing structures (such as a collapsing mine) But the majority of naturally-occuring earthquakes are caused by movements of the earth's plates, as we'll see in the next section. We only hear about earthquakes in the news every once in a while, but they are actually an everyday occurrence on our planet. According to the United States Geological Survey, more than three million earthquakes occur every year. That's about 8,000 a day, or one every 11 seconds! Photo courtesy FEMA Residential damage caused by the 1994 earthquake in Northridge, California. The vast majority of these 3 million quakes are extremely weak. The law of probability also causes a good number of stronger quakes to happen in uninhabited places where no one feels them. It is the big quakes that occur in highly populated areas that get our attention. Earthquakes have caused a great deal of property damage over the years, and they have claimed many lives. In the last hundred years alone, there have been more than 1.5 million earthquake-related fatalities. Usually, it's not the shaking ground itself that claims lives -- it's the associated destruction of manmade structures and the instigation of other natural disasters, such as tsunamis, avalanches and landslides. Photo courtesy NGDC Residential damage in Prince William Sound, Alaska, due to liquefaction caused by a 1964 9.2-magnitude earthquake. Sliding Plates The biggest scientific breakthrough in the history of seismology -- the study of earthquakes -- came in the middle of the 20th century, with the development of the theory of plate tectonics. Scientists proposed the idea of plate tectonics to explain a number of peculiar phenomenon on earth, such as the apparent movement of continents over time, the clustering of volcanic activity in certain areas and the presence of huge ridges at the bottom of the ocean. The basic theory is that the surface layer of the earth -- the lithosphere -is comprised of many plates that slide over the lubricating athenosphere layer. At the boundaries between these huge plates of soil and rock, three different things can happen: Plates can move apart - If two plates are moving apart from each other, hot, molten rock flows up from the layers of mantle below the lithosphere. This magma comes out on the surface (mostly at the bottom of the ocean), where it is called lava. As the lava cools, it hardens to form new lithosphere material, filling in the gap. This Photo courtesy USGS is called a divergent plate boundary. One of the best known faults is the San Plates can push together - If the two plates are moving toward Andreas fault in California. The fault, which marks the plate boundary between each other, one plate typically pushes under the other one. This the Pacific oceanic plate and the North subducting plate sinks into the lower mantle layers, where it American continental plate, extends over 650 miles (1,050 km) of land. melts. At some boundaries where two plates meet, neither plate is in a position to subduct under the other, so they both push against each other to form mountains. The lines where plates push toward each other are called convergent plate boundaries. Plates slide against each other - At other boundaries, plates simply slide by each other -- one moves north and one moves south, for example. While the plates don't drift directly into each other at these transform boundaries, they are pushed tightly together. A great deal of tension builds at the boundary. Where these plates meet, you'll find faults -- breaks in the earth's crust where the blocks of rock on each side are moving in different directions. Earthquakes are much more common along fault lines than they are anywhere else on the planet. In the next section, we'll look at some different types of faults and see how their movement creates earthquakes. Faults Scientists identify four types of faults, characterized by the position of the fault plane, the break in the rock and the movement of the two rock blocks: In a normal fault, the fault plane is nearly vertical. The hanging wall, the block of rock positioned above the plane, pushes down across the footwall, which is the block of rock below the plane. The footwall, in turn, pushes up against the hanging wall. These faults occur where the crust is being pulled apart, due to the pull of a divergent plate boundary. The fault plane in a reverse fault is also nearly vertical, but the hanging wall pushes up and the footwall pushes down. This sort of fault forms where a plate is being compressed. A thrust fault moves the same way as a reverse fault, but the fault line is nearly horizontal. In these faults, which are also caused by compression, the rock of the hanging wall is actually pushed up on top of the footwall. This is the sort of fault that occurs in a converging plate boundaryIn a strike-slip fault, the blocks of rock move in opposite horizontal directions. These faults form when the crust pieces are sliding against each other, as in a transform plate boundary Strike-slip fault In all of these types of faults, the different blocks of rock push very tightly together, creating a good deal of friction as they move. If this friction level is high enough, the two blocks become locked -- the friction keeps them from sliding against each other. When this happens, the forces in the plates continue to push the rock, increasing the pressure applied at the fault. If the pressure increases to a high enough level, then it will overcome the force of the friction, and the blocks will suddenly snap forward. To put it another way, as the tectonic forces push on the "locked" blocks, potential energy builds. When the plates are finally moved, this built-up energy becomes kinetic. Some fault shifts create visible changes at the earth's surface, but other shifts occur in rock well under the surface, and so don't create a surface rupture. Photo courtesy USGS Crop rows offset by a lateral strike slip fault shifting in the 1976 earthquake that shook El Progresso, Guatemala. The initial break that creates a fault, along with these sudden, intense shifts along already formed faults, are the main sources of earthquakes. Most earthquakes occur around plate boundaries, because this is where the strain from the plate movements is felt most intensely, creating fault zones, groups of interconnected faults. In a fault zone, the release of kinetic energy at one fault may increase the stress -the potential energy -- in a nearby fault, leading to other earthquakes. This is one of the reasons that several earthquakes may occur in an area in a short period of time. Photo courtesy USGS Railroad tracks shifted by the 1976 Guatemala earthquake Every now and then, earthquakes do occur in the middle of plates. In fact, one of the most powerful series of earthquakes ever recorded in the United States occurred in the middle of the North American continental plate. These earthquakes, which shook several states in 1811 and 1812, originated in Missouri. In the 1970s, scientists found the likely source of this earthquake: a 600-million-year-old fault zone buried under many layers of rock. The vibrations of one earthquake in this series were so powerful that they actually rang church bells as far away as Boston! In the next section, we'll examine earthquake vibrations and see how they travel through the ground. Making Waves When a sudden break or shift occurs in the earth's crust, the energy radiates out as seismic waves, just as the energy from a disturbance in a body of water radiates out in wave form. In every earthquake, there are several different types of seismic waves. Photo courtesy USGS Structural damage caused by vibrations from the 1964 Alaska earthquake Body waves move through the inner part of the earth, while surface waves travel over the surface of the earth. Surface waves -- sometimes called long waves, or simply L waves -- are responsible for most of the damage associated with earthquakes, because they cause the most intense vibrations. Surface waves stem from body waves that reach the surface. There are two main types of body waves. Primary waves, also called P waves or compressional waves, travel about 1 to 5 miles per second (1.6 to 8 kps), depending on the material they're moving through. This speed is greater than the speed of other waves, so P waves arrive first at any surface location. They can travel through solid, liquid and gas, and so will pass completely through the body of the earth. As they travel through rock, the waves move tiny rock particles back and forth -- pushing them apart and then back together -- in line with the direction the wave is traveling. These waves typically arrive at the surface as an abrupt thud. Secondary waves, also called S waves or shear waves, lag a little behind the P waves. As these waves move, they displace rock particles outward, pushing them perpendicular to the path of the waves. This results in the first period of rolling associated with earthquakes. Unlike P waves, S waves don't move straight through the earth. They only travel through solid material, and so are stopped at the liquid layer in the earth's core Both sorts of body waves do travel around the earth, however, and can be detected on the opposite side of the planet from the point where the earthquake began. At any given moment, there are a number of very faint seismic waves moving all around the planet. Surface waves are something like the waves in a body of water -- they move the surface of the earth up and down. This generally causes the worst damage because the wave motion rocks the foundations of manmade structures. L waves are the slowest moving of all waves, so the most intense shaking usually comes at the end of an earthquake. Pinpointing the Earthquake's Origin We saw in the last section that there are three different types of seismic waves, and that these waves travel at different speeds. While the exact speed of P and S waves varies depending on the composition of the material they're traveling through, the ratio between the speeds of the two waves will remain relatively constant in any earthquake. P waves generally travel 1.7 times faster than S waves. Using this ratio, scientists can calculate the distance between any point on the earth's surface and the earthquake's focus, the breaking point where the vibrations originated. They do this with a seismograph, a machine that registers the different waves. To find the distance between the seismograph and the focus, scientists also need to know the time the vibrations arrived. With this information, they simply note how much time passed between the arrival of both waves and then check a special chart that tells them the distance the waves must have traveled based on that delay. Photo courtesy USGS If you gather this information from three or more points, you can figure out A fence along a strike slip fault that shifted in the 1906 San Francisco the location of the focus through the process of trilateration. Basically, earthquake. you draw an imaginary sphere around each seismograph location, with the point of measurement as the center and the measured distance (let's call it X) from that point to the focus as the radius. The surface of the circle describes all the points that are X miles away from the seismograph. The focus, then, must be somewhere along this sphere. If you come up with two spheres, based on evidence from two different seismographs, you'll get a two-dimensional circle where they meet. Since the focus must be along the surface of both spheres, all of the possible focus points are located on the circle formed by the intersection of these two spheres. A third sphere will intersect only twice with this circle, giving you two possible focus points. And because the center of each sphere is on the earth's surface, one of these possible points will be in the air, leaving only one logical focus location. Rating Magnitude and Intensity Whenever a major earthquake is in the news, you'll probably hear about its Richter Scale rating. You might also hear about its Mercalli Scale rating, though this isn't discussed as often. These two ratings describe the power of the earthquake from two different perspectives. Photo courtesy NGDC Destruction caused by a (Richter) magnitude 6.6 earthquake in Caracas, Venezuela. The 1967 earthquake took 240 lives and caused more than $50 million worth of property damage. The Richter Scale is used to rate the magnitude of an earthquake -- the amount of energy it released. This is calculated using information gathered by a seismograph. The Richter Scale is logarithmic, meaning that whole-number jumps indicate a tenfold increase. In this case, the increase is in wave amplitude. That is, the wave amplitude in a level 6 earthquake is 10 times greater than in a level 5 earthquake, and the amplitude increases 100 times between a level 7 earthquake and a level 9 earthquake. The amount of energy released increases 31.7 times between whole number values. The largest earthquake on record registered an 9.5 on the currently used Richter Scale, though there have certainly been stronger quakes in Earth's history. The majority of earthquakes register less than 3 on the Richter Scale. These tremors, which aren't usually felt by humans, are called microquakes. Generally, you won't see much damage from earthquakes that rate below 4 on the Richter Scale. Major earthquakes generally register at 7 or above. For more information about the Richter Scale and seismographs, check out this Question of the Day. Photo courtesy NGDC Damage to a school in Anchorage, Alaska, caused by the 1964 Prince William Sound earthquake. The earthquake, which killed 131 people and caused $538 million of property damage, registered an 9.2 on the Richter Scale. Richter ratings only give you a rough idea of the actual impact of an earthquake. As we've seen, an earthquake's destructive power varies depending on the composition of the ground in an area and the design and placement of manmade structures. The extent of damage is rated on the Mercalli Scale. Mercalli ratings, which are given as Roman numerals, are based on largely subjective interpretations. A low intensity earthquake, one in which only some people feel the vibration and there is no significant property damage, is rated as a II. The highest rating, a XII, is applied only to earthquakes in which structures are destroyed, the ground is cracked and other natural disasters, such as landslides or Tsunamis, are initiated. Photo courtesy NGDC Damage from a magnitude 7.4 earthquake that hit Niigata, Japan, in 1964. Richter Scale ratings are determined soon after an earthquake, once scientists can compare the data from different seismograph stations. Mercalli ratings, on the other hand, can't be determined until investigators have had time to talk to many eyewitnesses to find out what occurred during the earthquake. Once they have a good idea of the range of damage, they use the Mercalli criteria to decide on an appropriate rating. Liquefaction In some areas, severe earthquake damage is the result of liquefaction of soil. In the right conditions, the violent shaking from an earthquake will make loosely packed sediments and soil behave like a liquid. When a building or house is built on this type of sediment, liquefaction will cause the structure to collapse more easily. Highly developed areas built on loose ground material can suffer severe damage from even a relatively mild earthquake. Liquefaction can also cause severe mudslides, like the ones that took so many lives in the recent earthquake that shook Central America. In this case, in fact, mudslides were the most significant destructive force, claiming hundreds of lives. Dealing with Earthquakes We understand earthquakes a lot better than we did even 50 years ago, but we still can't do much about them. They are caused by fundamental, powerful geological processes that are far beyond our control. These processes are also fairly unpredictable, so it's not possible at this time to tell people exactly when an earthquake is going to occur. The first detected seismic waves will tell us that more powerful vibrations are on their way, but this only gives us a few minutes warning, at most. Photo courtesy USGS Damage in downtown Anchorage, Alaska, caused by the 1964 Prince William Sound earthquake. Scientists can say where major earthquakes are likely to occur, based on the movement of the plates in the earth and the location of fault zones. They can also make general guesses of when they might occur in a certain area, by looking at the history of earthquakes in the region and detecting where pressure is building along fault lines. These predictions are extremely vague, however -- typically on the order of decades. Scientists have had more success predicting aftershocks, additional quakes following an initial earthquake. These predictions are based on extensive research of aftershock patterns. Seismologists can make a good guess of how an earthquake originating along one fault will cause additional earthquakes in connected faults. Another area of study is the relationship between magnetic and electrical charges in rock material and earthquakes. Some scientists have hypothesized that these electromagnetic fields change in a certain way just before an earthquake. Seismologists are also studying gas seepage and the tilting of the ground as warning signs of earthquakes. For the most part, however, they can't reliably predict earthquakes with any precision. So what can we do about earthquakes? The major advances over the past 50 years have been in preparedness -- particularly in the field of construction engineering. In 1973, the Uniform Building Code, an international set of standards for building construction, added specifications to fortify buildings against the force of seismic waves. This includes strengthening support material as well as designing buildings so they are flexible enough to absorb vibrations without falling or deteriorating. It's very important to design structures that can take this sort of punch, particularly in earthquake-prone areas. Photo courtesy USGS Bridge columns cracked by the Loma Prieta, Calif. earthquake of 1989. Another component of preparedness is educating the public. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) and other government agencies have produced several brochures explaining the processes involved in an earthquake and giving instructions on how to prepare your house for a possible earthquake, as well as what to do when a quake hits. To find out what you should do to prepare yourself, check out this online guide from the Red Cross. Photo courtesy USGS The great San Francisco fire of 1906 was initiated by a powerful earthquake. The earthquake vibrations and catastrophic fire destroyed most of the city, leaving 250,000 people homeless. In the future, improvements in prediction and preparedness should further minimize the loss of life and property associated with earthquakes. But it will be a long time, if ever, before we'll be ready for every substantial earthquake that might occur. Just like severe weather and disease, earthquakes are an unavoidable force generated by the powerful natural processes that shape our planet. All we can do is increase our understanding of the phenomenon and develop better ways to deal with it.