LECTURE 2: England in the Reign of Henry VIII (1509

advertisement

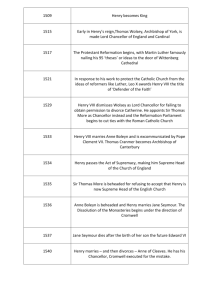

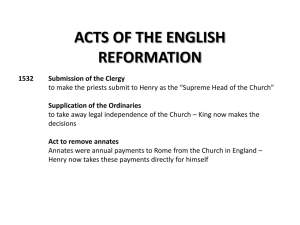

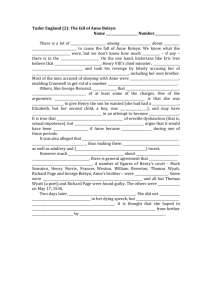

1 LECTURE 2: England in the Reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547) In 1520, approximately 6% of English people lived in urban centres, England was an overwhelmingly rural country with agriculture playing a predominant role in its economy, although trade was growing. The vast majority was formed by the peasantry (nearly all illiterate); the middle class included craftsmen and tradesmen; the gentry, were a propertied class living off the product of their estates but not working themselves (approx. 5% of the total population). The nobility was very exclusive: on Henry VIII’s accession in 1509 there were only 42 nobles and their powers had been diminished so they posed little threat to the king. However, as kingly authority was being asserted, it found itself more and more in conflict with the other great power of the time, the Catholic Church, with whom it shared some of its temporal control. It was during Henry VIII’s reign that England broke away from the authority of Rome and changed socially, but above all politically and religiously, beyond all recognition. I) A great conflict of power: the state against the Church A - One universal Church: monopoly The Church was a highly hierarchical body, as it still is today; priests at local level ran their parish churches and obeyed bishops, who ran their dioceses; they, in turn, obeyed archbishops (archdiocese, regional level), above whom were cardinals (national level) and at last, the pope. The Catholic Church was a supra-national structure [katholikos: Greek = universal. Church meant for the whole world, in contradistinction to the Jewish Church, designed for one nation] which was divided into national ‘lower orders’. This Church was all-powerful and its legitimacy was undoubted: this certainty was conveyed by the idea of direct apostolic succession: the uninterrupted transmission of authority, through bishops, from the apostles themselves at the time of Jesus Christ. The pope was considered infallible, the direct successor of St Peter. Monasteries (abbeys, priories, convents), operated under different orders with differing ‘rules’. Monasticism was a way of life determined by service to God, which for some meant helping the sick and the poor, providing education and preaching while for others it meant complete seclusion. B - Fiscal power: Monks and nuns were usually supported by begging, charity, donations, the farming of their own land, or legacies. But the Church as an institution was very rich, supported by taxes such as annates (the first year’s profit from bishoprics) and ‘Peter’s Pence’ (an annual tribute from every householder with lands). One of the most unpopular and difficult taxes was the tithes, which everybody paid specially to support the clergy: there were regular revolts against the tithes, and discontent was rife. Moreover, the clergy did not pay the taxes that everybody else, even the poor, had to pay: they were exempt. Instead, they called their own assembly every year (called the Convocation) and decided themselves how much money they were prepared to give the English state. People resented this unfair situation. Financially, the country paid many taxes which did not benefit its people or its government directly but served to fund the Church. Annates, chantries and donations to the Church were often perceived as a drain on English resources and gave the Church an uncomfortable degree of wealth and power. 2 C - Economic power: As if all this was not enough, the Church was also a major landowner whose wealth rivalled that of the crown in England. About 1/3 of English land belonged to the Catholic Church (to the monasteries); on this land, of course, were pastures and tenants paying rent at a time when the valued of land was rising very fast because of the increase in sheep rearing and enclosure of lands. This was a concern since the monasteries owed their allegiance to the pope rather than the king: the money went to Rome and entire areas felt remote from kingly authority. D - Political and judicial power: As well as possessing money, lands and judicial authority, the Church also wielded much political power; at the time, most educated men were clergymen. The predominance of clergymen in politics was also due to the fact that politicians were not paid by the state at that time. In order to earn a living, state servants must have another career, and this was usually the Church. Therefore, the government was constituted by a majority of churchmen, whose allegiance was divided between their temporal king (Henry VIII) and their spiritual king, (the pope). This was bound to cause problems since people in the highest echelons (such as the Lord Chancellor, who was the equivalent of today’s Prime Minister) were affected. For instance, Henry VIII’s first Lord Chancellor was Cardinal Wolsey, and we will see that his effort to please both his king and his pope were to send him to his death. The judicial system was also affected, since ecclesiastical courts settled all disputes relating to the clergy; if clergy were unhappy with a court’s decision, they could appeal to Rome for the sentence to be overruled, which undermined England’s national authority and law. Therefore, the Church at the time of Henry VIII had become a state within the state, uncontrollable, wealthy, powerful and usually arrogant enough to boast of all these things… with impunity. The common people, the lay landowners, the politicians and the king himself were beginning to resent this situation and to look for a way to curtail the Church’s excessive power. Yet it is important to remember that, at this early stage, the opposition to the Church was purely practical: it was political and economic, but in no way theological. Catholic doctrine was not under attack yet. The schism came to a head with the king’s Great Matter. II - The king’s Great Matter What is known as the king’s Great Matter is in fact something which might appear quite unproblematic to a person today: Henry VIII wanted a divorce from his first wife, Queen Catherine of Aragon, to marry his mistress, Anne Boleyn. Such an apparently trivial predicament led England on a collision course with the Church authorities of Rome and eventually brought about the momentous changes of the English Reformation. This divorce, an eminently private matter, would have unpredicted political and religious consequences. Although today people tend to know Henry VIII as a tyrannical Bluebeard character who had six wives, the issue of the divorce must not be oversimplified: although personal details are easier to remember (they are more colourful), the Great Matter was in part a debate about the will of the king, which was pitted against the will of the Church. Henry VIII had to assert his authority and define his rule as powerful. A - The background to the divorce 3 Towards the end of the 1520s, when the issue of the divorce arose, Catherine of Aragon, Henry VIII’s first wife and a very popular queen, was in her forties. She was physically exhausted by many pregnancies but had not managed to bear a male heir, she often miscarried, and when children were born, they died soon after. Only one child had survived, a daughter called Mary (later Queen Mary I, 1553-1558). Henry, for his part, had fallen in love with the young Anne Boleyn. But there was more to this situation: the divorce emerged also from a succession crisis; Henry VIII knew he could father a son, because he had just given a bastard son to his current mistress. He named him Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Sommerset, and tried to persuade Cardinal Wolsey to legitimise him. But the Cardinal refused: it would have been a scandal to have a bastard as heir to the throne. In this context, some historians argue that, as far as Henry was concerned, any female of child-bearing age would have done just as well. Anne Boleyn could have been a mistress if the matter of securing the dynasty had not been so pressing. The fact that his father Henry VII was the first Tudor monarch would have momentous impact upon Henry VIII. Because the Tudor dynasty was still young and fragile, he was under great pressure to have a son (to secure a male heir to the throne); but he had only one legitimate child, Mary; the king feared for the succession of the Tudor house and felt that marrying Boleyn was his only chance. In those circumstances, Henry wanted the pope to grant him an annulment. But Pope Clement VII had already granted him a special license to allow him to marry his brother’s widow, thereby making the marriage legal. He was not going to ‘dispense with his dispensation’ (Thomas More to Henry VIII). B - The route of diplomacy and canon law From 1527 to 1529, Henry VIII waited while his faithful Cardinal Wolsey tried the usual diplomatic and military solutions; but these were unsuccessful. Before their marriage in 1509, Henry and Catherine had obtained a licence to legitimise their union. In order to do so, they argued that Arthur’s marriage with Catherine had never been consummated; there was, therefore, nothing to prevent Catherine’s marriage to Henry. Now, in 1529, Henry wanted to get rid of Catherine; he instructed Wolsey to argue the exact opposite. By May 1529, Cardinal Wolsey’s lack of success made Henry impatient and led to Wolsey’s fall. He left London for York in April 1530, and died soon after. Henry’s new argument was based on the Bible, Leviticus, ch.18, which lays down the degrees of sexual uncleanness in the Law of ancient Israel. Verse 16 commands: ‘Thou shalt not uncover the nakedness of thy brother’s wife: it is thy brother’s nakedness’. Henry argued the marriage was therefore morally wrong and should be annulled at trials in Roman and English courts; he claimed that Catherine was lying when she said her marriage to Arthur had not been consummated. He declared she was not a virgin when he married her, and so the marriage was invalid. When all this came to nothing, Henry consulted all the most eminent minds on the Continent, at prestigious universities. However, the universities failed to offer a solution in Canon Law. There seemed to be no remedy to Henry’s problem in canon law; he would have to turn to temporal law. At that point, a newcomer in government, named Thomas Cromwell, came to replace Wolsey as the king’s main advisor; it was he who suggested the monarch should become supreme head of the Church in England, and he would be a crucial key in the movement towards Reformation. The very fact that Henry VIII, himself a devout Catholic, 4 had given two years of his time waiting for a solution to be found in Rome proved that he did no put the Catholic Church’s authority in question. As a Catholic subject, he felt Rome had power he did not have, like that of dissolving his marriage. It was Cromwell who pushed him further, and even then Henry advanced carefully, for political reasons only, and never abandoned the Catholic faith. C - Temporal law, the break with Rome Since the attempts to obtain the divorce through pressure on the papacy had failed, Wolsey's successor Thomas Cromwell (Henry's chief adviser from 1532 onwards) turned to Parliament, using its powers and its anti-clerical attitude to decide the issue. The result was a series of Acts curtailing papal power and influence in England and bringing about the English Reformation. The most important of those Acts were: 1) 1533, the Act in Restraint of Appeals to Rome This declared the English Church sufficient to deal with the divorce on its own and claimed for the first time : ‘This realm of England is an Empire’. 2) The Act of Succession (1534) By December 1532, Anne Boleyn was pregnant; to avoid any questions of the legitimacy of the child, Henry was forced into action. In January 1533, Anne and Henry were secretly married. Although the king's marriage to Catherine was not dissolved yet, the king had persuaded himself that it had never existed in the first place, so he was free to marry Anne. On May 23, the newly-appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, officially proclaimed that the marriage of Henry and Catherine was invalid and the king then had Anne Boleyn crowned. The Pope responded with a sentence of excommunication. The break with Rome was now complete; the Act of Succession was passed to make Anne the legitimate queen and to make sure her children with Henry VIII would be recognised as rightful heirs to the throne. It was meant to guarantee the legitimacy of the Tudor succession. Every English subject had to swear an Oath of allegiance to Henry VIII as head of the English church and state. Thomas More, his Lord Chancellor and internationally renowned humanist (author of Utopia), and John Fisher, saintly bishop of Rochester, refused to swear and were both executed as traitors in 1535. Henry had intended to execute Mary, his own daughter by Catherine of Aragon, because she also refused to swear. 3) The Act of Supremacy (1534) This was the climax of the whole episode of the schism and with it, Parliament legally declared the king to be the only Supreme Head of the Church of England. This denied the pope any power or authority in the affairs of the English Church and for the first time, the Church in England became entirely separate from the Church of Rome. It was still catholic, but it was English and national, ruled by the king and its own English hierarchy. Any foreign influence was denied. Conclusion: The irony was that (just like Catherine of Aragon before her) Anne Boleyn did not manage to produce a living male heir for Henry VIII. By August 1533, preparations were being made for the birth of the child, names were chosen, with Edward and Henry the top choices. The proclamation of the birth had already been written using the word 'prince' to refer to the child. On 7 September, Princess Elizabeth was born. Anne knew that it was imperative that 5 she produce a son, but she failed. She was right in thinking this was a threat to her own life, especially since the king's fancy for one of her ladies-in-waiting, Jane Seymour, began to grow.