Multi-Culture Factors: International Customer Service

advertisement

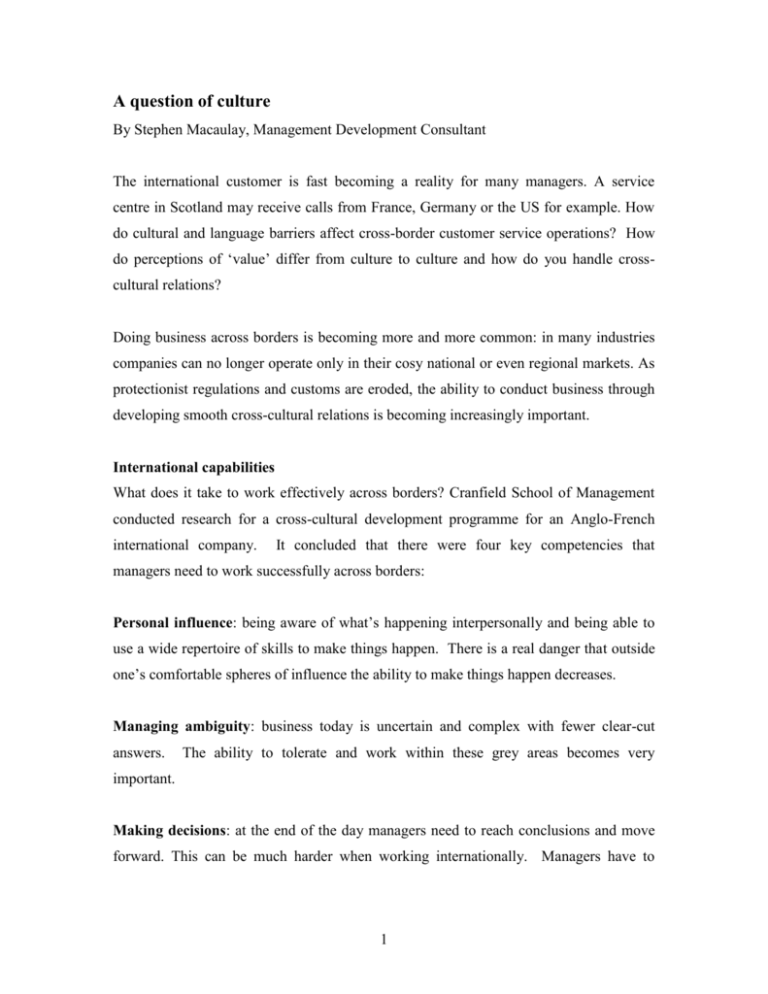

A question of culture By Stephen Macaulay, Management Development Consultant The international customer is fast becoming a reality for many managers. A service centre in Scotland may receive calls from France, Germany or the US for example. How do cultural and language barriers affect cross-border customer service operations? How do perceptions of ‘value’ differ from culture to culture and how do you handle crosscultural relations? Doing business across borders is becoming more and more common: in many industries companies can no longer operate only in their cosy national or even regional markets. As protectionist regulations and customs are eroded, the ability to conduct business through developing smooth cross-cultural relations is becoming increasingly important. International capabilities What does it take to work effectively across borders? Cranfield School of Management conducted research for a cross-cultural development programme for an Anglo-French international company. It concluded that there were four key competencies that managers need to work successfully across borders: Personal influence: being aware of what’s happening interpersonally and being able to use a wide repertoire of skills to make things happen. There is a real danger that outside one’s comfortable spheres of influence the ability to make things happen decreases. Managing ambiguity: business today is uncertain and complex with fewer clear-cut answers. The ability to tolerate and work within these grey areas becomes very important. Making decisions: at the end of the day managers need to reach conclusions and move forward. This can be much harder when working internationally. Managers have to 1 transfer knowledge into action, exercise discretion to make sound decisions and assume responsibility for making things happen. Customer focus: it is easy to get wrapped up in the difficulties of managing across borders and the customer can get lost in the process. Customers’ needs must be continually assessed as an integral part of the decision making process and solutions developed to meet their needs. Discussions with experienced international managers suggest these competencies are applicable in a wider context. Acting on the signals Managers working across national boundaries need to be able to read cultural signals successfully and to act on them appropriately. Unfortunately, the two do not always go hand in hand. If you are not very good at reading cultural signals, but you get on with it anyway, you are likely to be a ‘bull in a china shop’, making all kinds of mistakes. Almost as bad is where you read the signals fail to act on them, becoming in effect a dispassionate observer. This is a mistake in an international service context, where proactivity is key. What you want to do is both read the signals and act on them appropriately. International service managers need to take account of all the stakeholders in the service delivery chain. They need to be able to respond to the diverse needs of colleagues, business partners, employees, contractors and suppliers, as well as the end customer. Reading the context the customer is operating in is crucial. This includes not just the country, but the region, the industry they work in, the organisation they work for, the sort of technology they are used to handling, how they view their profession and their role, maybe even their gender. The manager of a multi-lingual service centre in Dublin commented: ‘We opened 18 months ago; we made so many incorrect assumptions about 2 our customers and our employees, which we now realise were all based on a British culture. It’s been a steep learning curve.’ Understanding different cultures Research pinpoints national differences around a small number of key dimensions, for example: Different attitudes to power and status. A British managing director and his team celebrated an alliance with a German company with his new colleagues. The next day, the German company called the deal off – the German CEO felt there was insufficient respect from British colleagues for their boss. It set the British company back 18 months How many rules people need to operate within. For instance French managers may prefer to know precise objectives and procedures; British managers seem to be happier to act and work out the how’s and why’s later. The importance of the individual versus the group. In the US individuality is very strong – much more so than with Swedish managers, for example, who value group decisions and consensus. The value of relationships, over getting the job done whatever the consequences: on a development programme with a group of Swedish managers the importance of relationships came out time and again, more so than with many English and US groups. Attitudes to expressing emotions also differ: in some countries frank discussions are not acceptable, even in a business context; in others it demonstrates a willingness to explore new ideas without restraint. Similarly, the US and northern European view of time is sequential – one event leads to another and can be planned and budgeted for. The 3 southern European approach is to juggle a series of tasks, so taking a phone call in a meeting is perfectly acceptable. To avoid problems, think about your own preferred communication style. Does the organisation have a common style? How much are national styles influencing you and the customer? You may have to adapt the way you communicate when you are dealing internationally. Be aware of the cultural context. Think carefully before you speak about the likely impact of your words: you may need to be more formal and careful in the use of humour. Be wary of stereotypes – they may be a useful template but they conceal as much as they reveal. At best they are a starting point for further exploration; at worst they are totally misleading. For short business assignments or visits, briefing on points concerning national characteristics which affect conducting business can be useful. However, it can take years to break down cultural barriers. Training and development to promote international teamworking and consciously communicating successes in cross-cultural working can play an important part. Shaping up to be more international Step 1 – Analyse the current situation It is easy to aim for the future and ignore the legacy of the past. But you will build a stronger future by drawing on your strengths - you may have a lot of diversity already. Ask yourself some hard questions. Do you have key influencers who champion the international customer? Is recruitment based on genuinely international criteria? Do you have a clear understanding of the diverse needs of your international customers? Do you talk the customer’s language – not just in words, but in a genuine understanding of what is important to them? Workshops can provide a rich understanding of the culture and reveal an agenda for change. For example, during a series of workshops, a financial services business concluded that its culture was based on an unshakeable belief that it would endure and 4 that mistakes would be punished. These attitudes led to poor customer service, an unhelpful risk aversion and heavy, standardised controls. In moving to a more flexible international culture, it had to change this mindset and the way it dealt with others. Step 2 – Set improvement goals An essential part of successfully managing change is to involve others - individuals need to understand and be committed to make personal change. An international workforce is typically well educated and interested in the business. This demands clear and regular communication of the process. Step 3 – Implement these goals What leaders do to support the international customer is undoubtedly very powerful and can be helped along by symbolic actions. When I worked at British Airways I helped to promote the removal of separate offices for managers, to encourage a more open, flexible and less hierarchical customer environment. The strong feelings this generated suggested the true nature of this symbolic act! Training and development can be a significant vehicle of cultural change. To be effective, however, it will need move beyond the generalities and to probe underlying assumptions about and attitudes towards other cultures. Step 4 – Sustain the impetus Building an international focus is not a one-off event - people leave and new people join and the customer profile changes. A continuous process of reinforcing, updating and sustaining is required. Learn from mistakes To work successfully across cultures, you will need to adopt management approaches that take account of the complex differences between customers. Start with a candid assessment of yourself and your organisation, including assumptions and stereotypes held. Valuing alternative points of view and demonstrating respect for other people are crucial skills, but hard to make a reality. Misunderstandings will inevitably arise. How 5 you handle them and learn from them will determine how whether you make a success of working internationally. 6