Faruk_Merali - Higher Education Academy

advertisement

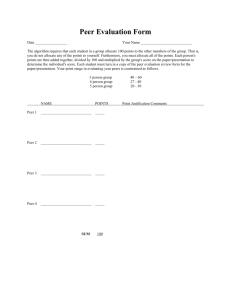

Exploring the different attitudes and experiences of UK domiciled versus International MBA students towards peer assessment Higher Education Academy Annual Conference 2008 1 - 3rd July 2008, Harrogate International Centre, Harrogate. st Faruk Merali Senior Lecturer in Organisational Behaviour London Metropolitan University London Metropolitan Business School Stapleton House, 277-281 Holloway Road, London N7 8HN E mail: f.merali@londonmet.ac.uk ABSTRACT This study reports a clear difference in the attitudes and experiences of UK domiciled students compared to international students towards peer assessment and student self-determination of assessment criteria which was recently introduced within an MBA module. The differences in the views of the two student groups are presented and their implications discussed. Introduction There is significant literature related to exploring student attitudes and experiences of peer assessment (Brown et al, 2003; Cheng & Warren, 1997; Hanrahan & Isaacs, 2001; Smith et al, 2002; Van den Berg et al, 2006, Pope, 2005), however this usually tends not to distinguish between the views, attitudes and experiences of locally domiciled versus international students. The studies that do specifically investigate any differences in the attitudes and experiences of home versus international students to the various assessment methods (including peer assessment) and the pedagogic implications of any cultural differences tend to be sparse (De Vita, 2002; Gatfield, 1999). Furthermore the existing literature appears to focus upon peer assessment experiences mainly in relation to undergraduate as opposed to postgraduate student experiences (Van den Berg et al, 2006, Gatfield, 1999; Hanrahan & Isaacs, 2001; Pope, 2005; Smith et al, 2002). In recent years there has been an increase in the number of international students within the UK higher education sector (De Vita, 2002). This has led to a growing interest in the significance of literature related to culture and cross cultural management (Hofstede, 1980; Trompenaars, 1993; Hall, 1976) and its relevance to the field of pedagogy (Gatfield, 1999; Wu, 2002). Hofstede’s (1980) classical global oriented research based in HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 40 countries and involving a survey of 116,000 IBM employees led to the identification of five key cultural value based dimensions (power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity and confusion dynamism) which have been found to be useful in identifying national cultural differences. The cultural dimension relating to power distance denotes the extent to which unequal power distribution is acceptable within organisations and society whereas uncertainty avoidance reflects the extent to which uncertainty and unpredictability are tolerated. Countries that rank high on the cultural dimension of individualism and masculinity prefer values related to competitiveness, assertiveness and have a preoccupation with taking care of oneself rather than values associated in relation to the welfare of the wider collective group. The dimension labelled “confusian dynamism” was identified later (Hofstede & Bond, 1988) and relates to the maintenance of short-term and long-term orientation. Similarly Trompenaars (1993) distinguished national cultural differences based on seven dimensions (universalism versus particularism; individualism versus collectivism, neutral versus affective relationships, specific versus diffuse relationships, achievement versus ascription and relationship to time). Hall (1976) on the other hand developed a High and Low Context Cultural Framework for explaining differences in communication styles within various national cultures. Whilst there has been some criticism that some of these studies (such as that of Hofstede (1980)) may be dated given the global political, economic and social changes that have taken place over the last two decades, more recent studies (Sondergaard, 1994; Smith et al 1996) have largely confirmed that Hofstede’s work is still relevant to contemporary society despite the global changes that have taken place. Collectively therefore these studies related to national cultural differences provide an interesting framework not only for providing an insight into differences in national cultures but are also significant to pedagogy in relation to understanding and managing the effective learning and teaching of both home and international students in higher education within a multi cultural environment (Gatfield, 1999). Through undertaking primary research this study aims to contribute to the relative gap in the existing research by seeking to identify, compare and discuss the similarities and differences in the views and attitudes of UK domiciled versus international postgraduate students towards engaging in a peer assessment process which included the determination by the students of their own group assessment criteria. Methodology As part of an action research project, a peer assessment exercise was introduced within four separate cohorts of MBA students (two part time HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 2 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 and two full time) enrolled to study a Managing People module taught at a Business School in London. Peer assessment was introduced in relation to the UK domiciled student cohort who were all part time students in the spring semesters of 2006-07 (to one cohort of 10 students) and 2007-08 (to a second cohort of 15 students). For the international students who were all full time students this was implemented in the autumn semester (to one cohort of 25 students) and spring semester of 2007-08 (to a second cohort of 21 students) with some minor refinements made following feedback and reflection from the implementation of the scheme in the preceding year as a result of this action research project. The same tutor facilitated the teaching of both student groups. In the past the module had been assessed partly through group training sessions consisting of small teams of four to five students. These sessions were jointly marked by two tutors who also set the marking criteria. It was decided to replace this approach with peer assessment for pedagogic reasons so as to develop effective critical skills and encourage deeper student learning (Falchikov, 1986, Brown et al, 2003). In order to encourage total student ownership of the assessment process and to facilitate deeper student learning, students were encouraged and provided support by the tutor towards determining their own group assessment criteria (Brown & Knight, 1994). As a result of introducing the peer assessment scheme within the module, each student formally peer assessed the group training sessions (except their own) which accounted for 50% of the module assessment. The students were provided with considerable information, advice and guidance by the module tutor throughout the period leading up to the formal peer assessment exercise which was conducted towards the end of each semester. As part of the action research project the four cohorts of students were introduced to the peer assessment exercise in 2006-07 and 2007-08 and some minor refinements to the scheme were made in 2007-08 following feedback from the students and reflection from the implementation of the scheme in the preceding year. These refinements included the introduction of mock training sessions in class during the semester which were jointly reviewed by the students and tutor and the provision of additional guidance on compiling assessment criteria through sharing with the students some of the sample training session criteria forms from the previous semester. The UK domiciled students were all part time students (n=25) who worked in full time supervisory or managerial related positions within London. The international students (n=46) who were all full time students had a minimum of two years of supervisory/managerially related experience and came from twelve different countries (Indian subcontinent: 23; China: 2; Middle East: 1; Sub-Saharan Africa: 8; HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 3 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 Europe 10; S.America: 1 and USA: 1). The international and UK domiciled students had a similar mode age range of 26-30 years. Feedback in relation to the students’ views, attitudes and perceptions of the formal peer assessment exercise including the setting up of their own group assessment criteria was elicited through the completion of openended questionnaires both before and soon after the peer assessment exercise. All students were assured of confidentiality in relation to their responses. Whilst all students returned completed pre-peer assessment questionnaires, 19 of the 25 UK domiciled students and 37 of the 46 international students returned completed post-peer assessment questionnaires. A few questions were occasionally left unanswered in the questionnaires. Findings The peer assessment process was introduced to four different cohorts of MBA students (two separate cohorts of UK domiciled students and two separate cohorts of international students) but since the student numbers are relatively small, for the purpose of this paper the findings from the two combined international (n=46) and two combined UK domiciled groups (n=25) are reported. The findings below are categorised in terms of the feedback elicited from the pre-peer assessment questionnaires and post-peer assessment questionnaires. Feedback from the pre-peer assessment questionnaires The pre-peer assessment questionnaires were issued to students at the beginning of the semester prior to the introduction of the peer assessment exercise in order to identify whether the students had been exposed to any previous experience of peer assessment and to elicit their views, attitudes and feelings about the proposed peer assessment exercise. All the students returned completed pre-peer assessment questionnaires. In relation to having any prior experience of setting up of their own formal assessment criteria, the feedback indicated that only one international student had been involved in this within his previous studies. The remainder UK domiciled and international students reported that they had never been involved in setting their own formal assessment criteria within their previous educational experience. A majority of these students (i.e. 19 of the UK domiciled students and 44 of the international students) indicated that they felt they would find the process of determining their own formal assessment criteria a useful and valuable HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 4 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 experience. Five of the six remaining UK domiciled students indicated that they weren’t sure whether this experience would be valuable and ticked “don’t know” in the questionnaires whereas one indicated that she felt that assessment criteria set by the lecturer would be more challenging. The two international students who indicated that they did not think this experience would be valuable did not provide a reason for this view. As far as the peer assessment process was concerned, eight students (three UK domiciled and five international students) reported that they had been engaged in peer assessment exercises within their previous educational experience though only six of these students (two UK domiciled and four international students) reported that they had found this to be a valuable experience. Nineteen of the UK domiciled students compared to 41 of the international students indicated that they thought a peer assessment exercise would be a valuable experience. Except for one student the remainder weren’t sure whether the experience would be valuable and ticked “don’t know” in the questionnaires. One international student reported that he did not think this would be a valuable experience as he was concerned that his peers might engage in assessing in a political and tactical manner. Feedback elicited from the post-peer assessment questionnaires All students were issued with a post-peer assessment questionnaire soon after the completion of the peer assessment exercise. Nineteen of the 25 UK domiciled students and 37 of the international students returned completed post-peer assessment questionnaires. A few questions were occasionally left unanswered in the questionnaire. A summary of the main student feedback elicited from the post-peer assessment questionnaires is provided in Table 1 below. Table 1: Post-Peer Assessment Student Feedback Student Feedback 1. Found setting own group assessment criteria to be beneficial 2. Felt happy to set their own group assessment Aggregate: Full Time International MBA Students (n=37) 32/*35 (91%) Aggregate: Part Time Home UK Domiciled MBA students (n=19) 10/19 (53%) (* 2 students did not answer this question) 33/37 (89%) HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 5 10/19 (53%) Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 criteria in the future 3. Preferred peer assessment to tutor based assessments 4. Felt positive about peer assessing another group’s training session 5. Felt final mark awarded by peers was a fair representation of the assessed training session performance 6. Felt they would be happy to be peer assessed again in the future 7. Felt positive overall about the peer assessment process 31/37 (84%) 7/19 (37%) 29/*35 (83%) 9/*16 (56%) (* 2 students did not answer this question) (* 3 students did not answer this question) 31/37 (84%) 14/19 (74%) 34/37 (92%) 14/19 (74%) 30/*32 (94%) 11/*14 (79%) (* 5 students did not answer this question) (* 5 students did not answer this question) A sub-analysis of the responses of the international students exclusively from the eastern hemisphere countries (n=25), which included countries from the Indian subcontinent, Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and China, was also undertaken. This sub-analysis did not reveal any significant difference to that of the international student group taken as a whole. The following extracts from the student feedback questionnaires convey the key sentiments expressed by the students in relation to the summary provided in Table 1. With regards to the responses to the question “How did you feel about setting your own assessment criteria? What benefits and/or drawbacks did this have for you?”, the following two extracts represents the generally positive sentiments expressed by the international students: “It was an extremely good experience because we had to meet our own criteria and think about it, which is, in my opinion, the base for a (sic) good decision making for every manager (if one can’t meet his/her own criteria, than (sic) it’s certainly difficult to meet the criteria of others). Not to mention the importance of setting up the right criteria and then meeting those!”. International student Autumn 2007-08. “The design of our own assessment criteria gave us an overview of what would be the main focus on the training session”. International student Spring 2007-08. HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 6 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 On the other hand the following two extracts from the UK domiciled students represents the generally less favourable sentiments expressed by this group of students: “I think allowing groups to set their own criteria is questionable. This is because on any course all the students should be judged on the same criteria and standards for all modules. By allowing us to set our own criteria there is inconsistency on what we are being measured against…my preference would have been for all study groups to be assessed by the same criteria. If the aim is to enable interaction with setting the assessment criteria, the entire class could discuss and come to a consensus on the criteria during class”. UK domiciled student Spring 2007-08. “Setting my own assessment criteria wasn’t a great learning experience but it did help you to focus more on structuring and compiling your presentation in a certain way”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. With regards to the question: “Would you be happy to be involved in setting up your own/your group’s assessment criteria in the future? Why?”, the following three extracts from the questionnaires completed by the international students reflects the views of the majority of their peers: “Yes I would. It is the most effective way to start and plan what the training session is going to contain”. International student Autumn 2007-08. “Yes, it helps my individual development”. International student Spring 2007-08. “Yes as I thought this was very good experience and it made you think harder about the assessment process and also in the training session made you concentrate harder on what other groups were doning (sic)”. International student Spring 2007-08. The following two extracts relating to the UK domiciled students represents the general concerns expressed by their peers: “Not really, too much (sic) issues and stress”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. “No because I don’t see the point of peer assessment”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. In connection to the question: “How did you feel about having your peers assess your group training session rather than the tutor?”, the following three extracts reflected the majority view by the international students who mainly reported preferring peer assessment to tutor based assessment: HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 7 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 “I can get different opinions and perspective from peers” International student Autumn 2007-08. “To be honest, I felt more comfortable. “The distress syndrome of being assessed by the Tutor” was not there. This allowed us to act more relaxed”. International student Spring 2007-08. “I felt great as the training session was delivered to our peers not the tutor”. International student Spring 2007-08. On the other hand the following extract represents the reservations expressed towards peer assessment by many of the UK domiciled students: “I didn’t feel very comfortable. After reading some of the comments I realised that peers’ assessment was quite biased and subjective in some cases. I would think the tutor’s mark would be much fairer and more objective”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. In relation to the question: “How did you feel about peer assessing another group’s training session? What benefits and/or drawbacks did this have for you?”, the majority of the international students expressed a positive experience. These views are represented by the two extracts below: “I felt good assessing others work because I got an idea of what are the possible mistakes we can make and I also felt that when I assess others work I tend to listen more carefully into(sic) the task”. International student Autumn 2007-08. “I think it’s a good, challenging and interesting way to learn”. International student Spring 2007-08. On the other hand the following two extracts represent the concerns expressed by the UK domiciled students towards their experiences of peer assessment: “Again I did not like doing this. I feel that I did not come away learning anything from the presentation that I had to mark. However, I felt that I had to give a higher mark than what I actually gave because if I put what I really felt, it would drive the groups mark down by quite a lot...I can’t see any benefits in peer assessment. I think criteria setting and marking should be left to a neutral party, the teacher”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. “Did not enjoy this task”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. With regards to the question: “Do you think the final mark awarded to you by your peers was a fair representation off your assessed training HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 8 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 session performance? Why?”, the positive response rate was generally similar from both groups of students. The following five extracts represent their sentiments: “Yes, it was fair because what we deserved we get (sic)”. International student Autumn 2007-08. “Yes. Because I personally don’t think we did the an excellent job (sic). As well as we were one of the lowest scored marks in the whole class which I feel was fair”. International student Autumn 2007-08. “I think it was fair enough. It could have been better. There were few aspects in our training session which were not covered wheich (sic) will be taken care of in future”. International student Spring 2007-08. “I thought we did a very professional training session and this was reflected in the mark”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. “Yes. I understood the reasons behind both positive and negative comments throughout the assessment and would probably have come to a similar mark”. UK domiciled student Spring 2007-08. A minority of the students from both the groups felt that their final mark was not fair and this is represented by the two extracts below: “Final mark we got from peers was below my expectations, I expected even more. Why? - our team tried our best! We provided real questionnaire that could be found at many interviews with big international companies”. International student Autumn 2007-08. “I felt the content of my teams presentation was a lot better than the other group’s but the result didn’t reflect that”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. In relation to the question: “Would you be happy to be peer assessed again? Why?”, the majority of the students in both groups expressed a positive response (though the positive responses from the international students was higher compared to the UK domiciled students). The following extracts represent the positive views from both groups of students along with some of the reservations that were expressed: “Yes, it is an opportunity for self improvement”. International student Autumn 2007-08. “Yes. The benefits I’ve described before are quite significant to justify this type of assessment”. International student Spring 2007-08. “Yes, overall good experience”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 9 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 “Most definitely. There are (sic) some sense of value when your peers give you feedback”. UK domiciled student Spring 2007-08. “No, I’d like the tutor to mark. Tutors have special training qualification and experience and thus I would trust their marks as much more objective and fair”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. “No, don’t think its entirely fair, don’t see the point, think this should be left to the teacher”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. In relation to the last question in the questionnaire: “Any overall comments including your overall feelings about the peer assessment process ?”, both groups of students mainly reported a positive overall experience (though once again the positive response rate was higher amongst the international students compared to the UK domiciled student cohort). The following extracts represent the views of both the groups: “I am happy with the entire process which we have gone through in the whole peer assessment period. It was a good way to know how people see us not how we see us. And thanks to our tutor to give us such a wonderful opportunity in entire whole module”. International student Autumn 2007-08. “Good keep it up for other MBA’s”. International student Spring 2007-08. “Not much happy (sic) because of few peers being irresponsible throughout the process”. International student Autumn 2007-08. “It was a very bold move to introduce this method at an MBA level module final assessment. Going by the results, it has definitely paid off in terms of a good and acceptable outcome (grades). More importantly, it forced peers into a position of serious responsibility, accountability and control, whereby they have had to park their personal biases aside and be fair in their judgement”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07. “It was a new and novel way of learning – I enjoyed it”. UK domiciled student Spring 2007-08. “It can be more nerve racking than being assessed by your tutor”. UK domiciled student Spring 2006-07 Overall the findings demonstrate a difference in the attitudes and experiences of UK domiciled students compared to international students towards the peer assessment exercise and student self-determination of assessment criteria especially in relation to the statements numbered 1-5 in Table 1. The international students were significantly more positive about the student self-determination of the assessment criteria and HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 10 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 generally about the peer assessment process than their part time UK domiciled peers. As far as statements 5-7 in Table 1 are concerned, a difference is still evident between the views and attitudes of the two cohorts of students with the international students demonstrating more positive sentiments compared to their UK domiciled peers although the difference is not as marked. Discussion Although the student numbers involved in this study are relatively small, this research provides a qualitative based insight into the peer assessment based learning experiences of UK domiciled and international students. In this study the overall differences in attitudes and views towards the peer assessment process and the determination of assessment criteria by the UK domiciled students compared to the international students is notable and worthy of further analysis and consideration. A previous studies by Gatfield, (1999: pg 372) had reported a “substantive positive difference in the perceptions of international students in comparison with Australian (home) students…” however the paper did not provide an in-depth discussion of thee possible reasons underpinning these differences. The literature related to culture and cross cultural management (Hofstede, 1980; Trompenaars, 1993; Hall, 1976) may provide a useful basis to analyse and discuss the differences in the views and attitudes expressed by the two cohorts of students in relation to the peer assessment exercise. With this in mind since a large number (n=25) of the full time international students involved in this research are from mainly from the eastern hemisphere (countries of the Indian subcontinent, Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and China) an understanding of their national cultures is warranted. The Indian subcontinent appears to be classified as having a “large power distance and collectivist” dimension according to Hofstede’s model (1980) whilst China’s national culture is similarly categorised by Hofstede (1993) and Trompenaars (1993). It was therefore considered that the students from these countries (which collectively form the majority group within this study) maybe more likely to favour the peer assessment process which facilitated the group work through determining their group assessment criteria and assessing each other’s group training sessions in line with the collectivist cultural dimension. Furthermore these students may also be responding positively to the tutor’s suggestion and encouragement to adopt the peer assessment process since the tutor is seen as a respected individual who should not be challenged in line with the large power distance dimension. However in this study a sub-analysis of the international students exclusively from the eastern hemisphere countries (i.e. the countries of the Indian HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 11 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 subcontinent, Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and China) did not reveal any significant difference from that of the international student group as a whole. This may be attributed to the small numbers of students involved in this study but would be an interesting area for further research within a larger international student cohort. As far as UK cultural dimensions are concerned, the UK is classified by Hofstede (1980) to be located within the contrasting dimension of small power distance and individualist. It could therefore be argued that UK based students are likely to prefer non-team based approaches in line with the individualist dimension and could therefore likely to be more apprehensive with the peer assessment process which may explain their responses in this study. This relatively limited study highlights the potential importance for higher education practitioners to develop an understanding of the cultural background of their students and the implications of any differences when developing effective approaches and strategies for teaching, learning and assessment within a multi-cultural environment. For example a study by Cheng & Warren (1997) identified the need to be sensitive to cultural influences among Chinese students during the assessment process. The authors of this study found that not exposing mistakes publicly and not criticising directly was important for a homogenous group of Hong Kong Chinese students, however they did not compare their findings with students from different cultural backgrounds. Further research is needed to develop a deeper insight into the implications of international cultural differences for effective student teaching, learning and assessment. In-depth qualitative interviews with individual international and home students or with appropriate focus groups representing a large and diverse range of students from different cultural backgrounds is likely to generate a richer insight into these key issues. HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 12 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 References: Berg, I. van den, Admiraal, W and Pilot, A (2006). Design principles and outcomes of peer assessment in higher education, Studies in Higher Education, 31(3), 341-356. Brown, S and Knight, P (1994). Assessing Learners in Higher Education, London: Kogan Page. Brown, G; Bull, J and Pendlebury M (2003). Assessing Student Learning in Higher Education, London and New York: Routledge. Cheng, W and Warren, M (1997). Having Second Thoughts: student perceptions before and after a peer assessment exercise, Studies in Higher Education, 22(2). 233-239. De Vita, G (2002). Cultural Equivalence in the Assessment of Home and International Business Management Students: a UK exploratory study, Studies in Higher Education, 27(2). 221-231. Falchikov, N (1986). Product comparisons and process benefits of collaborative peer group and self assessments, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 11. 146-166. Gatfield, T (1999). Examining Student Satisfaction with Group Projects and Peer Assessment, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 24(4). 365-377. Hall, ET (1976). Beyond Culture. New York: Doubleday/Currency. Hanrahan, SJ and Isaacs, G (2001). Assessing Self- and Peer-assessment: the students’ views, Higher Education Research & Development, 20(1). 53-70. Hofstede, G (1980). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values, London: Sage. Hofstede, G and Bond, MH (1988). The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth”, Organizational Dynamics, 16. 4-21. Hofstede, G (1993). Cultural Constraints in Management Theories, Academy of Management Executive, 7. 81-94. Pope, N (2005). The impact of stress in self and peer assessment, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(1). 51-63. HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 13 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008 Smith, H., Cooper, A and Lancaster, L (2002). Improving the Quality of Undergraduate Peer Assessment: A Case for Student and Staff Development, Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 39(1), 71-81. Smith, PB; Dugan, S and Trompenaars F (1996). National culture and the values of organizational employees: a dimensional analysis across 43 nations, Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 27. 231-264. Sondergaard, M (1994). Research note: Hofstede’s Consequences: a study of reviews, citations and replications, Organizational Studies, 15(3). 447-456. Trompenaars, F (1993). Riding the Waves of Culture. London: Nicholas Brealey. Wu, S (2002). Filling the Pot or Lighting the Fire? Cultural Variations in Conceptions of Pedagogy, Teaching in Higher Education, 7(4). 387-395. HE Academy Annual Conference July 2008 14 Paper presented: 3rd July 2008