Binge Drinking and Violent Assaults of Indigenous Australians of NT

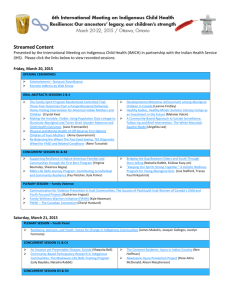

advertisement

Submission in response to the Australia’s National Drug Strategy Beyond 2009 Consultation Paper Associate Professor Tricia Nagel Dr Rama Jayaraj Anthony Ah Kit Valerie Thompson Neil Spencer Menzies School of Health Research John Mathews Building Royal Darin Hospital Campus Casuarina NT 0810 This submission represents the view of the above individuals rather than the institution. Introduction The Northern Territory (NT) demonstrates many of the hazards of problem drinking in Australia. We have the highest estimated rates of per capita alcohol consumption (Matthews et al. 2002) and these high rates have persisted over many years (Chikritzhs et al. 2000; Stockwell et al. 2000). Indigenous people comprise 32% of the NT population but suffer much higher proportions of the negative outcomes of substance misuse (Perkins et al. 1994) (Kowalyszyn and Kelly 2003). While the mortality rate due to alcohol has dropped nation wide, the rate of hospitalisations from alcohol-caused injury and disease has rapidly increased. The leading cause of hospitalisations was alcohol dependence while alcohol-caused death was primarily associated with alcoholic liver cirrhosis (National Drug Research Institute 2009). The percentage of hospitalisations among Indigenous males for conditions associated with high levels of alcohol use were between two and seven times higher than for non-Indigenous males in 2002–2003 (Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2005). There remains a significant gap in our knowledge and understanding of the link between alcohol misuse and harm, especially in remote communities (Gray et al. 2006; Matthews et al. 2002). Our knowledge of the trends in substance use in remote communities is also limited (Clough et al. 2002) and little is known about the association between problem drinking and assaults (Kelly and Kowalyszyn 2003). It is not known to what extent alcohol use directly leads to violence. What is known is that while alcohol consumption among all Territorians has been known to be consistently high (Gray et al. 2000) (Matthews et al. 2002) and Darwin has long held the status of the highest alcohol consuming capital in the world (Alcohol-Related Violence Growing in Darwin 2010) alcohol related violence statistics have been rising. Key Point There is a need to understand the link between alcohol misuse and harm, especially in remote communities. February 2010 1 Changes over time Alcohol consumption has only recently become an accepted social habit among Indigenous Australians (Brady 1997). Today its consequences are unacceptable. Nation wide Indigenous Australians are six times more likely than non-Indigenous people to drink at high-risk levels (Chikritzhs and Brady. 2006). Indigenous men are more likely to consume alcohol at risky levels than Indigenous women, while women are more likely to begin risky consumption at younger ages (25-34 years) compared with Indigenous men (34-44 years) leading to major health concerns in their child bearing years (National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey). Colonisation has been linked with suffering for Indigenous peoples which continues to the present day. Racism and separation from family and land continues to impact upon the health of Indigenous people (Kowanko I et al. 2004; Paradies Y 2006; Zubrick SR et al. 1995). Substance misuse is one of the many negative social consequences of the avalanche of change experienced since the first settlers arrived. The pattern of drinking, too, is linked with history and cultural conflict. Binge drinking was encouraged by the lack of legal access for Indigenous Australians to drinking venues (Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy 2006). This prohibition was only lifted in the last few decades, thus there has only been a relatively short span of time in which to develop and test successful treatment and intervention strategies. There is a need for innovation which looks beyond the ‘disease’ and abstinence approaches of the past, to an understanding of individual and community risk which calls for individual and community wide strategies. While separation from family, land, and culture is linked with emotional distress there is evidence that community development approaches to health improvement which strengthen culture and empower communities have shown success (Burgess P et al. 2008; Rowley K et al. 2000). Historic and cultural factors have influenced the pattern of drinking and the severity of alcohol related distress (Alati R et al. 2000). This has led to a multitude of approaches to treatment. Attempts to harness Indigenous Australia’s cultural identity and cultural strength in provision of harm reduction strategies have been limited. Often the time that is needed for ‘proper’ community consultation is not invested. Proper consultation is inclusive of the whole community. Many current supply reduction strategies are merely prohibition in modern guise, reminiscent of historic forms of social control and political oppression of Indigenous peoples. The way forward will be to develop new approaches which strengthen cultural identity and social inclusion, promote cultural continuity and challenge institutionalised racism (Kirmayer L 2003; Murray R et al. 2002). It is emotional distress and intergenerational trauma which usually drives substance misuse, and emotional distress which is most often its hidden consequence. Conversely it is resilience and well being which will provide protection from substance misuse and emotional distress for current and future generations (Chandler M and Proulx T 2006; Chandler and Lalonde 1998). Strategies which promote wellbeing, identity and cultural continuity must be implemented, whether community-wide, family focused or targeting individuals (Murray R et al. 2002). Key point There needs to be greater recognition of the emotional distress which drives substance misuse and exploration of community development strategies to build resilience. February 2010 2 Alcohol related injury, assault and hospitalisation Crime, hospital, inmate and community statistics provide insight into the problem of injury and assault among Indigenous peoples. Nationally, homicide and violence accounted for 16% of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander injury burden (Anderson 2008). Violence was the most common cause of hospital admission for injury in the NT (You and Guthridge 2005) accounting for 38% of the total injury admissions for Indigenous people. It is not clear to what extent these crimes are perpetrated by intoxicated people, or to what extent victims and perpetrators are Indigenous, however Indigenous prisoners are vastly overrepresented in the NT. They currently represent 82% (850) of the daily average prison population. Evidence of the link between violence, assault and alcohol misuse is scant. Reports from offenders clearly link alcohol in violent assaults and crime (Morgan and McAtamney 2009). The Drug Use Monitoring Australia (DUMA) program reported that 50% of all offenders detained by police across Australia in 2007 for disorder and violent offences had consumed alcohol in the 48 hours prior to their arrest (Adams et al. 2007). It is known that factors which influence transition from remote communities to Darwin are: family violence, lack of housing, over crowding in communities and easy access to alcohol in Darwin (Catherine and Eva 2008) and that the harm associated with high risk alcohol consumption in Indigenous Australians includes family conflict, domestic violence and assaults (Kelly and Kowalyszyn 2003; Kowalyszyn and Kelly 2003). Further, it has been reported that most of the assaults against women in remote NT communities, are perpetrated by a drunken husband or other family member (Barber et al. 1988). Although the factors which render alcohol-fuelled violence more likely are not fully understood, there is evidence that some places represent greater risk compared with others. Both customers and employees of licensed premises are at more serious risk of becoming involved in a violent incident than other locations (Graham and Homel 2008 ). Premises for the consumption of alcohol and the location of assaults are always interconnected with much greater rates of alcohol-related violence and fighting, particularly among non-indigenous males, than any other setting (Poynton 2005; Teece and Williams 2000; Wells 2005) (McIlwain and Homel 2009). In contrast, the close family members and friends involved in the group drinking activity face greater risk in the Indigenous context, and it is likely that the site for Indigenous assaults reflects where the drinking is taking place (bushes or private homes or parks or narrow pathways). Whatever the drinking location, facial trauma is a frequent end result of alcohol-fuelled violence. Key point There is a need to better understand the context of alcohol fuelled violence and the risk factors for facial injury secondary to assault. Alcohol-related facial trauma Binge drinking is strongly linked with violence-related facial trauma (Gassner et al. 1999) and high risk alcohol consumption is an important contributor to such trauma in the Indigenous population. The incidence of facial fractures in the Northern Territory (more than 350 per year) is by far the highest in the world. While only 32% of the population is Indigenous, 60% of all facial fractures seen are in Indigenous patients and 89% of these are a result of interpersonal violence (Thomas and Jameson. 2007). February 2010 3 Facial injury is often accompanied by emotional distress. In addition to the restoration of physical appearance and functional status for those who face violent associated facial trauma, there is also an urgent need for psychosocial care (Wong et al. 2007). There is an increasing consciousness of the risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the incidence of violence-related facial injury (Bisson et al. 1997; Lento et al. 2004; Roccia et al. 2005a; Roccia et al. 2005b) and depression is also reported as a result of facial injury (Hull et al. 2003a; Hull et al. 2003b; Levine et al. 2005). In this setting of emotional distress the additional problem of substance misuse complicates rehabilitation (Passeri et al. 1993). In the NT Indigenous population pathways to recovery will be further complicated by cultural difference. Key point There is a need to develop integrated assessment and treatment for combined emotional distress (and cultural and spiritual distress), alcohol misuse and facial injury Strategies for change A comprehensive array of supply reduction, harm reduction, and demand reduction strategies are recommended in the complementary action plan of the national drug strategy addressing Indigenous Australians. In the NT, a range of supply reduction strategies have been introduced including: restricting take away sales, restricting cask sizes, and limiting trading hours (d'Abbs and Togni 2000; Hogan et al. 2006). The key take home message from The ‘Living with Alcohol’ program (1992 -2002) in the Northern Territory (NT) was that interventions can make a difference, and that the components of success include a focus on treatment services and broader awareness raising campaigns linked with supply reduction through alcohol taxes (ChikritzhsT et al. 2004). Turning to harm reduction strategies in the NT, these have generally focused on custodial care and residential treatment. ‘Night patrols’ in Darwin often provide free transport to safe locations such as sobering-up shelters or the police watch house for intoxicated rural and remote Indigenous Australians under custodial care legislation. Sobering-up shelters are neither detoxification centres, nor rehabilitation centres, but provide temporary refuge or asylum for intoxicated individuals at risk of causing harm to themselves or others. They also redirect intoxicated Indigenous population from police custody. Sobering-up centres provide temporary care for high risk individuals and the opportunity for brief interventions by drug and alcohol workers, and referrals for further assistance (Brady et al. 2006). They are only one component of a comprehensive approach to harm reduction, however, and there is as yet no evidence of effectiveness of these albeit limited interventions. Key point There is a need to explore the effectiveness of sobering up shelters and other options for custodial care as harm reduction strategies. Treatment for Indigenous substance misuse Political and socio-cultural influences underpin the vulnerability of Australian Indigenous peoples to high risk binge drinking. Strategies to address supply reduction must be mixed with culturally adapted treatment approaches. These approaches need to directly address the February 2010 4 underlying socio-political causes of emotional distress and substance misuse, which include disempowerment and cultural discontinuity. They need to build an Indigenous workforce able to advocate strongly and treat effectively using community, family and individual approaches which promote cultural identity, kinship and the cultural values of Australian Indigenous peoples. In specialist treatment settings (rehabilitation services for example) culturally adapted strategies for treatment and models of understanding have only recently begun to flourish (Brady 2007; Brady M et al. 1998). Indigenous rehabilitation services have struggled with issues of isolation secondary to political and historic influences (Alati R et al. 2000). This has led to services which operate separate to mainstream with little evidence of effectiveness and limited systems for self evaluation (Brady M 2002). As a result there is a strong push for engagement of Indigenous services with mainstream services but a clear risk that adopting a ‘one size fits all’ approach will not work given differences of worldview, language and literacy (Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy 2006). This risk will apply to outcome measures as well. Measuring the success of interventions will require the application of culturally valid outcome measures and acknowledgement that differences of world view and cultural framework affect such measures. There have been important recent attempts to investigate and explore culturally adapted models of service delivery and outcome measurement (Nagel T 2007; Nagel T et al. 2008; Schlesinger CM et al. 2007). These recent studies have resulted from exploration of the high comorbidity of substance misuse with mental illness. This is a strong reason why a focus on supply reduction must work hand in hand with development of treatment services. Limiting the supply of one particular intoxicant will not address the underlying emotional distress within individuals, families and communities that drives its use. Key point A focus on supply reduction must work hand in hand with development of treatment services which nurture strong partnerships with Indigenous service providers and use culturally validated outcome measures. Evidence that culturally adapted treatment may be effective stems from a mixed methods study in two remote communities in the NT. This study showed that participatory action research can result in tools for treatment which can be developed and successfully applied in resource-poor cross cultural settings. A brief psychological intervention was tested, using a randomised controlled design, in the setting of comorbid substance dependence and mental health and found to be effective (Nagel T 2007; Nagel T et al. 2008; Nagel T et al. 2009b; Nagel T and Thompson C 2007). Concurrent development of Indigenous specific screening tools has further added to the cross cultural resources available in the field (Schlesinger CM et al. 2007). Additional positive change in the field is the development of a community based Indigenous workforce which is developing its own model of engagement with communities using principles of community development combined with best practice in brief interventions (Nagel T et al. 2009a). These two recent NT initiatives represent important new directions toward engaging the strength of culture in development of resilience and resistance to substance misuse. February 2010 5 Key point There is a need for evaluation and expansion of community preventive and treatment initiatives which are developed in collaboration with Indigenous peoples and integrate community development approaches. Conclusion Political and socio-cultural influences underpin the vulnerability of Australian Indigenous peoples to high risk binge drinking. There is an epidemic of alcohol fuelled assault which is frequently the result of family violence and is frequently complicated by facial injury. These high rates of alcohol misuse and injury are likely to be driven by underlying distress and link with high rates of mental and physical illness, social disadvantage and incarceration. Strategies to address supply reduction must be mixed with culturally adapted treatment approaches. These approaches need to directly address the underlying socio-political causes of emotional distress and substance misuse, which include disempowerment and cultural discontinuity. They need to build an Indigenous workforce able to advocate strongly and treat effectively using community, family and individual approaches which promote cultural identity, kinship and the cultural values of Australian Indigenous peoples. Key point Many of the above issues are specific to the context of Indigenous peoples and support the relevance of a separate National Drug Strategy Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Complementary Action Plan References Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal. 2007. Alcohol killed 1145 Indigenous Australians in five years: 'one-size-fits all' doesn't work: researchers. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal 32(2):14-15. Adams K, Sandy L, Smith L, and Triglone B. 2007. Drug use monitoring in Australia (DUMA):2007 annual report on drug use among police detainees. Research and public policy series no 93 Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology URL:http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current series/rpp/81-99/rpp93.aspx. Alati R, Peterson C, and Liamputtong Rice P. 2000. The Development of Indigenous Substance Misuse Services in Australia: Beliefs, Conflict and Change. Australian Journal of Primary Health-Interchange 6(2):49-62. Alcohol-Related Violence Growing in Darwin A. 2010. Alcohol Rehab. URL:http://wwwalcoholrehabtreatmentcenterscom/research-news/alcohol-relatedviolence-growing-in-darwin-australia/. Anderson I. 2008. An analysis of national health strategies addressing Indigenous injury: consistencies and gaps. Injury 39 Suppl 5:S55-60. Barber JG, Punt J, and Alberts J. 1988. Alcohol and power on Palm Island. Australian Journal of Social Issues 32:89-101. Bisson JI, Shepherd JP, and Dhutia M. 1997. Psychological sequelae of facial trauma. The Journal of trauma 43(3):496-500. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, and Grumbach K. 2002. Patient Self-management of Chronic Disease in Primary Care. JAMA 288(19):2469-2475. Brady M. 1997. Aboriginal drug and alcohol use: recent developments and trends. Aust NZ J Public Health 21:3–4. February 2010 6 Brady M. 2007. Equality and difference: persisting historical themes in health and alcohol policies affecting Indigenous Australians. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61(9):759-763. Brady M. 2002. Indigenous residential treatment programs for drug and alcohol problems: Current status and options for improvement Discussion Paper No. 236. The Australian National University. Brady M, Dawe S, and Richmond R. 1998. Expanding knowledge among Aboriginal service providers on treatment options for excessive alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review 17:69-76. Brady M, Sibthorpe B, Bailie R, Ball S, and Sumnerdodd P. 2002. The feasability and acceptability of introducing brief intervention for alcohol misuse in an urban medical service. Drug and Alcohol Review 21:375-380. Brady M, Nicholls R, Henderson G, and Byrne J. 2006. The role of a rural sobering-up centre in managing alcohol-related harm to Aboriginal people in South Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev 25(3):201-206. Burgess P, Mileran A, and Bailie R. 2008. Beyond the mainstream: Health gains in remote Aboriginal communities. Australian Family Physician 37(12). Catherine H, and Eva M-W. 2008. An investigation into the influx of Indigenous ‘visitors’ to Darwin’s Long Grass from remote NT communities – Phase 2 Monograph Series No. 33. URL:http://wwwhomelessnessinfonetau/dmdocuments/being_undesirable-_law_health_and_life_in_darwins_long_grasspdf. Chandler M, and Proulx T. 2006. Changing Selves in Changing Worlds: Youth Suicide on the Fault-Lines of Colliding Cultures. Archives of Suicide Research 10(2):125-140 (116). Chandler MJ, and Lalonde C. 1998. Cultural Continuity as a Hedge against Suicide in Canada's First Nations. Transcultural Psychiatry 35(2):191-219. Chikritzhs T, and Brady. M. 2006. Fact or fiction? A critique of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2002. Drug Alcohol Rev 25(3):277-287. Chikritzhs T, Heale P, and Webb M. 2000. Trends in alcohol-related road injury in Australia, 1990–1997. National Alcohol Indicators Bulletin No. 2. Perth and Melbourne: National Drug Research Institute and Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre Chikritzhs T, and Pascal R. 2004. Trends in youth alcohol consumption and related harms in Australian jurisdictions 1990–2002. National Alcohol Indicators Bulletin No 6 URL: www.ndri.curtin.edu.au/pdfs/naip/naip006.pdf. ChikritzhsT, Stockwell T, Pascal R, and Catalano P. 2004. The Northern Territory’s Living With Alcohol Program, 1992-2002: revisiting the evaluation Perth, WA: National Drug Research Institute Curtin University of Technology,. Clough AR, Baille R, Burns CB, Guyula T, Wunungmurra R, and Wanybarrnga SR. 2002. Validity and utility of community health workers' estimation of kava use. Aust N Z J Public Health 26(1):52-57. Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 1999. National health priority areas report. Mental health: a report focusing on depression, 1998. Canberra: The Department and AIHW, (AIHW Cat. No. PHE 11.), . http://wwwaihwgovau/publications/health/nhpamh98/nhpamh98pdf (accessed Aug 2007) Crundall I, and Moon C. 2003. Report to the Licensing Commission:summary evaluation of the Alice Springs liquor trial.Darwin: Northern Territory Government,. d'Abbs P, and Togni S. 2000. Liquor licensing and community action in regional and remote Australia: a review of recent initiatives. Aust N Z J Public Health 24(1):45-53. February 2010 7 D’abbs P, and Togni S. 1997. The Derby Liquor Licensing Trial: a report on the impact of restrictions on licensing conditions between 12 January 1997 and 12 July 1997 (Darwin, Menzies School of Health Research). Dempsey K, and Condon J. 1999. Mortality in the Northern Territory 1979 – 1997. Darwin: Epidemiology Branch, Territory Health Services. Gassner R, Bosch R, Tuli T, and Emshoff R. 1999. Prevalence of dental trauma in 6000 patients with facial injuries: implications for prevention. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics 87(1):27-33. Graham K, and Homel R. 2008 Raising the bar: preventing aggression in and around bars, pubs and clubs. Devon, UK. Willan Publishing. Gray D. 2000. Indigenous Australians and liquor licensing restrictions. Addiction 95(10):1469-1472. Gray D. 2003. Review of the summary evaluation of the Alice Springs Liquor Trial: a report to Tangentyere Council and Central Australian Aboriginal Congress. Perth: NDRI, Curtin University of Technology,. Gray D, Pulver LJ, Saggers S, and Waldon J. 2006. Addressing indigenous substance misuse and related harms. Drug Alcohol Rev 25(3):183-188. Gray D, Saggers S, Atkinson D, Sputore B, and Bourbon D. 2000a. Beating the grog: an evaluation of the Tennant Creek liquor licensing restrictions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 24(1):39-44 Gray D, Saggers S, Sputore B, and Bourbon D. 2000b. What works? A review of evaluated alcohol misuse interventions among aboriginal Australians. Addiction 95(1):11-22. Hogan E, Boffa J, Rosewarne C, Bell S, and Chee DA. 2006. What price do we pay to prevent alcohol-related harms in Aboriginal communities? The Alice Springs trial of liquor licensing restrictions. Drug Alcohol Rev 25(3):207-212. Hull AM, Lowe T, Devlin M, Finlay P, Koppel D, and Stewart AM. 2003a. Psychological consequences of maxillofacial trauma: a preliminary study. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery 41(5):317-322. Hull AM, Lowe T, and Finlay PM. 2003b. The psychological impact of maxillofacial trauma: an overview of reactions to trauma. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics 95(5):515-520. Hunter EM, Hall W. D, and M. SR. 1992. Patterns of alcohol consumption in the Kimberley aboriginal population. Med J Aust 156:764–768. Keel M. Australian Institute of Family Studies. Family violence and sexual assaults in Indigenous communities. ACSSA Briefing No. 4, September 2004. Kelly AB, and Kowalyszyn M. 2003. The association of alcohol and family problems in a remote indigenous Australian community. Addictive behaviors 28(4):761-767. Kirmayer L SC, Cargo M,. 2003. Healing traditions: culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Australasian Psychiatry 2003 (supplement). Kowalyszyn M, and Kelly AB. 2003. Family functioning, alcohol expectancies and alcoholrelated problems in a remote aboriginal Australian community: a preliminary psychometric validation study. Drug Alcohol Rev 22(1):53-59. Kowanko I, de Crespigny C, Murray H, Groenkjaer M, and Emden C. 2004. Better medication management for Aboriginal people with mental health disorders: a survey of providers. Aust J Rural Health 12:253-257. Lento J, Glynn S, Shetty V, Asarnow J, Wang J, and Belin TR. 2004. Psychologic functioning and needs of indigent patients with facial injury: a prospective controlled study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 62(8):925-932. February 2010 8 Levine E, Degutis L, Pruzinsky T, Shin J, and Persing JA. 2005. Quality of life and facial trauma: psychological and body image effects. Annals of plastic surgery 54(5):502510. Martin R, Wyatt K, and Harrison J. 2005. National Public Health Partnership: The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Safety Promotion Strategy. wwwnphpgovau. Matthews S, Chikritzhs T, Catalano P, Stockwell T, and Donath S. 2002. Trends in AlcoholRelated Violence in Australia, 1991/92-1999/00. . National Alcohol indicators Bulletin 5. McIlwain G, and Homel R. 2009. Sustaining a reduction of alcohol related harms in the licensed environment: a practical experiment to generate new evidence. Brisbane: Key Centre for Ethics, Law, Justice & Governance, Griffi th University. . http://wwwgriffitheduau/professional-page/professor-ross-homel/pdf/ReducingViolence-in-Licenses-Environments_2009pdf. Measuring Crime Victimisation A-TIoDCM, 2002 (cat. no. 4522.0.55.001), . 2005. Crime and Safety, Australia. Memmott Pea. 2001. Violence in Indigenous communities. Canberra: Attorney General’s Department Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy. 2006. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Complementary Action Plan 2003–2009. Canberra: National Drug Strategy Unit. Morgan A, and McAtamney A. 2009. Key issues in alcohol-related violence. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Murray R, Bell K, Elston J, Ring I, Frommer M, and Todd A. 2002. Guidelines for development, implementation and evaluation of national public health strategies in relation to ATSI peoples. Melbourne, Vic: National Public Health Partnership. Nagel T. 2007. Motivational care planning: brief interventions in Indigenous mental health. Australian Family Physician 37(12):996-1001. Nagel T, Frendin J, and Bald J. 2009a. Interim Report AOD Remote Workforce in the NT. Darwin: Remote Workforce Program. Nagel T, Robinson G, Condon J, and Trauer T. 2008. An approach to management of psychotic and depressive illness in indigenous communities. Australian Journal of Primary Health Care 14(1):17-21. Nagel T, Robinson G, Condon J, and Trauer T. 2009b. Approach to treatment of mental illness and substance dependence in remote Indigenous communities: Results of a mixed methods study Aust J Rural Health 17(174-82). Nagel T, and Thompson C. 2007. AIMHI NT ‘Mental Health Story Teller Mob’: Developing stories in mental health. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health (AeJAMH) 6(2). Nagel T, Thompson C, Spencer N, Judd J, and Williams R. 2009c. Two way approaches to Indigenous mental health training: Brief training in brief interventions. Australian eJournal for the Advancement of Mental Health (AeJAMH) 8(2). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey -, (NATSIHS). National Drug Research Institute PHDUIA. 2002. Alcohol-related Violence A Major Cause Of Injury In Australia, Media Release, . URL: http://dbndricurtineduau/mediaasp?mediarelid=33. National Drug Research Institute PHDUIA. 2009. Alcohol-caused death rates decline but hospitalisations keep on rising, Media Release. URL:http://ndricurtineduau/research/naipcfm Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2005. URL: http://wwwpcgovau/gsp/reports/indigenous/keyindicators2005. February 2010 9 Paradies Y. 2006. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol 35(4):888-901. Passeri LA, Ellis E, 3rd, and Sinn DP. 1993. Relationship of substance abuse to complications with mandibular fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51(1):22-25. Perkins JJ, R. W S-F, S B, D L, S R, and M. J H. 1994. The prevalence of drug use in urban Aboriginal communities. Addiction 89(10):1319-1331. Poynton S, et al,. 2005. The role of alcohol in injuries presenting to St Vincent’s Hospital Emergency Department and the associated short-term costs. Alcohol studies bulletin no 6 http://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/bocsar/ll_bocsar.nsf/vwFiles/ab06.pdf/$file/ab 06.pdf Roccia F, Dell'Acqua A, Angelini G, and Berrone S. 2005a. Maxillofacial trauma and psychiatric sequelae: post-traumatic stress disorder. The Journal of craniofacial surgery 16(3):355-360. Roccia F, Tavolaccini A, Dell'Acqua A, and Fasolis M. 2005b. An audit of mandibular fractures treated by intermaxillary fixation using intraoral cortical bone screws. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 33(4):251-254. Rowley K, Daniel M, Skinner S, Skinner M, WHite G, and O'Dea K. 2000. Effectiveness of a community-directed 'healthy lifestyle' program in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 24(2). Schlesinger CM, Ober C, McCarthy MM, Watson JD, and A S. 2007. The development and validation of the Indigenous Risk Impact Screen (IRIS): a 13-item screening instrument for alcohol and drug and mental health risk. Drug and Alcohol Review 26(2):109-117. Stockwell T, Chikritzhs T, and Brinkman S. 2000. The role of social and health statistics in measuring harm from alcohol. Journal of substance abuse 12(1-2):139-154. Swan A, Sciacchitano L, and Berends L. 2008. Alcohol and other drug brief intervention in primary care. Fitzroy, Victoria: Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre. Teece M, and Williams P. 2000. Alcohol-related assault: time and place. Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice no. 169. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. http://wwwaicgovau/publications/current series/tandi/161-180/tandi169aspx. Thomas ME, and Jameson. C. 2007. Facial trauma and post interventional quality of life in the Northern Territory, Australia. . International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery 36(11):1081. . Wells Sea. 2005. Drinking pattern, drinking contexts and alcohol-related aggression among late adolescent and young adult drinkers. Addiction 100:933–944. Wong EC, Marshall GN, Shetty V, Zhou A, Belzberg H, and Yamashita DD. 2007. Survivors of violence-related facial injury: psychiatric needs and barriers to mental health care. General hospital psychiatry 29(2):117-122. You J, and Guthridge S. 2005. Mortality, morbidity and health care costs of injury in the Northern Territory, 1991-2001. Health gains planning, Department of Health and Community Services Northern Territory Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Garton A, Burton P, Dalby R, Carlton J, Shepherd C, and Lawrence D. 1995. Western Australian Child Health Survey: Developing Health and Well-being in the Nineties. Perth, WA: Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Institute for Child Health Research. February 2010 10