THEKING`SREFORMATION.htm

advertisement

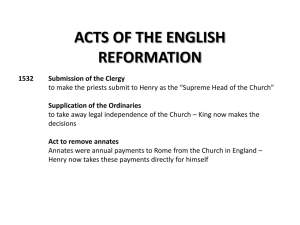

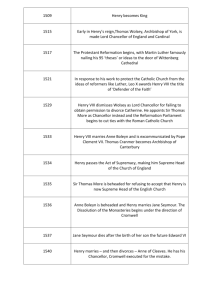

THE KING’S REFORMATION Henry VIII's break with Rome remains among the most striking and important, but also much misunderstood, events in English history. This novelty of the distinctive account and analysis offered in this book lies in an emphasis throughout - against the fashionable concentration on ministers and factions - on VIII's leading personal role, a king who ruled as well as reigned. My book also gives due weight, for the first time in a single volume, to those who would not accept what was imposed upon them, and to those who tried, at different times and in varying ways, to deflect the king from his purpose. What the king sought is shown to have been more consistent and more radical than has generally been allowed. The book concludes with troubling reflections on Henry's methods, seen as approaching tyranny, and an assessment of the lasting legacy of the Henrician Reformation. The book begins with Henry's discovery that his marriage to Catherine of Aragon was invalid - and with his passion for Anne Boleyn. Against the legend, it is Henry, not Anne, who is presented here as holding back from full sexual relations until they could wed. The account of Henry's campaign to secure the divorce from the pope highlights the king's frequent and early threats against papal powers: these are read not as bluster but as prophetic. But if he were to act independently, Henry would still need the support of the church in England: through a series of measures and pressures recounted here, Henry ultimately secured the acquiescence of churchmen in his royal supremacy. The famous Reformation parliamentary statutes are presented as ratifying the steps the king had already taken. Yet neither the divorce nor the break with Rome proceeded without dissent. Successive chapters explore the reactions of Catherine of Aragon, the Nun of Kent, Bishop Fisher and Sir Thomas More, Charterhouse monks and Observant friars, and other dissenters, to the king's demands. This analysis of those opposed to Henry's policies emphasises the personal, rather than political, character of much of their dissent. Catherine did not form 'the nucleus of a political party' (Froude), nor was she the progenitor of an 'Aragonese faction'; Fisher and More bore witness to the truth as they saw it, rather than organising political resistance or some underground movement. Henry's need to assert his royal supremacy against actual and potential opposition, and his image of himself as a reforming monarch who would purify the church from the abuses of the past, led to significant reforms. Too often religious policy in the 1530s and 1540s has been presented as fluctuating and inconsistent as Henry, himself seen at most as a secular figure rapaciously bent on seizing the wealth of the church, was supposedly influenced on religious matters first by one group of courtiers and counsellors and then by another, a view memorably expounded by the martyrologist John Foxe. 'Even as the king was ruled and gave ear sometimes to one, sometimes to another, so one while it went forward, at another season as much backward again, and sometimes clean altered and changed for a season, according as they could prevail, who were about the king'. Here I wish to overturn such tenacious misinterpretations. In this book, Henry emerges as the ultimate decision maker, very much the dominant force in the making of religious policy. A flashback to explore the piety of the king as revealed before the dramatic events of the break with Rome shows Henry as devout in his attachment to the mass and surprisingly competent as a polemicising theologian, but somewhat detached from many features of traditional religion, especially pilgrimages and monasteries. Influenced by Erasmus, Henry believed that the church was in need of purifying reform. The king's encouragement of Cardinal Wolsey's direction of the church is presented in that light. The visitation of the monasteries in 1535 reflected the king's determination to assert his authority. It uncovered what was understandably, but not entirely fairly, seen as evidence of abuses, especially sexual misconduct. In turn that led to the dissolution of the smaller monasteries by act of parliament in 1536, here seen as a sincerely reforming measure and not as the first step in a preconceived programme of overall dissolution. Henry also faced the need, in an age of increasing religious diversity and discord, to set out what true religion was. If Henry was more deeply committed to purifying reform than has generally been allowed, he was no Lutheran and remained fundamentally hostile to the central Lutheran tenet of justification-by-faith-alone. The liturgical and doctrinal changes announced in the Ten Articles and Injunctions of 1536 were the first of Henry's attempts to set out a middle way between Rome and Wittenberg. But the break with Rome and these early reforming measures, provoked, I contend, the risings in the north of England, known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. In substantial chapters I offer a reconsideration of these rebellions, presenting them as popular and counter-revolutionary movements directed against religious policies, especially the dissolution, but ranging more widely. I show how after apparently appearing on the brink of success, the rebels were defeated by a ruthlessly calculating king. Their ultimate failure had profound effects. The rebellion intensified the king's hostility towards the monasteries: the consequence was the final suppression of the monasteries, achieved by induced 'voluntary' surrender. Henry's efforts to set out true religion are then considered further. The Bishops' Book (1537), the royal proclamation of 16 November 1538, the Injunctions of 1538, the proclamation of 26 February 1539, the Act of Six Articles (1539) and the King's Book (1543) are each scrutinised in depth and set in the wider context of royal policy, notably the dissolution of the monasteries and the suppression of pilgrimage shrines. That leads to a substantial challenge to what has become the fashionable orthodoxy among professional historians, the notion of Henry as a weak man and the plaything of factions, dominated in turn by a Wolsey or a Cromwell. Henry's participation in debates over the nature of true religion, his copious annotations on various statements of faith, and his letters arguing with leading churchmen point rather to a ruler who was very much in command. But Henry's religious policy cannot be characterised as 'catholicism without the pope'. Instead it is here presented as reflecting the king's largely consistent search for a middle way - a middle way that was significantly different from traditional religion but that rejected central tenets of Luther's teachings. Since Thomas Cromwell, Henry's leading minister, has often but misleadingly - been seen as an influential and often successful advocate of evangelical if not protestant reform, interweaved with these analyses is a reassessment of Cromwell's religion, dealing in particular with the English translation of the Bible, religious controversy in Calais, negotiations with German protestant princes and Henry's marriage to Anne of Cleves. Conventional wisdom is overturned: Cromwell emerges as the king's energetic servant but not as a counsellor pushing independent ideas. And a fresh interpretation is offered of the fall of Cromwell in 1540, dismissing religious faction, and stressing rather how the king brought about Cromwell's fall as a means of advancing his middle way. Cranmer's religion is also reassessed. The conclusion draws on two themes running through the book. A review of the methods and pressures by which Henry imposed the break with Rome, securing compliance and crushing opposition, makes a case for seeing Henry's rule as tyranny. The book ends by considering the larger impact and legacy of Henry's search for a middle way, both on contemporaries, and in on the church of England as it was to develop, not least since it was Henry's settlement that, after a brief period of greater reform in the reign of his son and of reaction under his elder daughter Mary, that was taken up and consolidated by his daughter Elizabeth. Many of the lasting ambiguities and tensions of the church of England are to be best understood as the legacy of Henry VIII's ruthlessness and of his search for a middle way. THE KING’S REFORMATION 1. HENRY VIII'S DIVORCE AND THE BREAK WITH ROME Origins; Anne Boleyn The campaign for the divorce Henry VIII's case for the divorce Henry VIII's challenge to papal authority The threats against the church The break with Rome 2. OPPOSITION Catherine of Aragon The Nun of Kent Friars and monks Bishop John Fisher Sir Thomas More Fisher's episcopal colleagues Noblemen and parliament Reginald Pole 3. ROYAL SUPREMACY AND REFORM The The The The defence of the royal supremacy piety of Henry VIII reform of the monasteries Ten Articles (1536) 4. REBELLION The Lincolnshire Rebellion: The place of rumours The rebels' demands The Pilgrimage of Grace The rebellion spreads The character of the rebellion Monasteries and the Pilgrimage of Grace From apparent victory to defeat Reginald Pole The legation The fall of the marquess of Exeter 5. THE SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES Attainders and surrenders Refoundations? The generalisation of 'voluntary' surrender Compliance, reluctance, resistance Glastonbury, Colchester, Reading 6. THE SEARCH FOR THE MIDDLE WAY The Bishops' Book (1537) The proclamation of 16 November 1538 John Lambert The injunctions of 1538 The Six Articles (1539) Cromwell's religion Cromwell and Calais The search for alliances with German princes Henry's marriage to Anne of Cleves The fall of Cromwell and the middle way The King's Book (1543) CONCLUSION The tyranny of Henry VIII Henry's religious legacy