Inside and Outside Spooner`s Natural Law

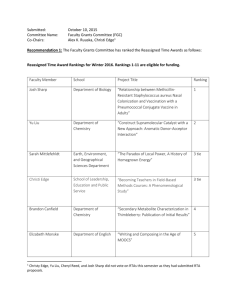

advertisement