Approaches of Teaching Listening in the Language Lab

advertisement

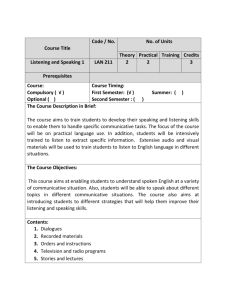

Approaches of Teaching Listening in the Language Lab The article I read is about approaches of teaching listening in the language lab. The author, Judith Tanka, conducted a survey at American Language Center’s Intensive English Program at the University of California, Los Angeles (ALC). The first approach is the teacher-controlled listening lab. As a whole, a lab instructor selected and broadcasted a program to ALC students scheduled in the language lab one hour a day, five times a week. Upon recording the program to their tape decks, students replayed the material so often and necessarily as to understand it thoroughly or, in the case of pronunciation drills, they had to do this until the could approximate the model. What the instructor did was to served as a monitor, listening on students, correcting pronunciation errors, answering questions, and providing answer keys to exercises. The goal was to provide varied input and occasionally to reinforce grammar or content covered in other classes. Without prescribed curriculum, the choice of listening materials was made entirely by the teacher. The lessons were easy to be run, and minimal preparation was required. However, the lack of explicit teaching of listening strategies and the absence of communicative listening tasks make the lessons begin to gravitate to the individualized listening library approach. The second one is the self-access and self-study listening lab. Students were still required to attend 5 hours a week and were asked to keep a daily log of materials and lessons they selected. The role of the teacher was to demonstrate samples of materials during the first week; for the rest of the term, was to become a resource person and monitor who was familiar with specific language problems and who would guide the students to the appropriate materials. With extensive quantities of comprehensible input, students would develop their listening proficiency by “osmosis”(Scarcella & Oxford, 1992, p.140) with no special instruction. Students controlled over their own learning. It seemed to reduce anxiety, but some problems surfaced. This system didn’t fit every student’s learning styles and expectations. Students from cultures that were teacher centered found the choices in the lab confusing and felt shortchanged when there was no specific teaching. Others with low motivation didn’t seem to take full advantage of the listening opportunities and progressed in listening poorly. The teachers began to think if leaving students to their devices and to control their own learning was the best way to listening teaching. The final one is the communicative language laboratory. The ALC decided to swing back to the teacher-centered language lab with a different approach. The goal of the lesson was to integrate the explicit teaching of listening strategies (For example, to form hypotheses, predict, guess form contextual and phonological clues, and draw inferences) with giving students enough opportunities to these strategies and transfer them to new tasks. To achieve this goal, written curriculum guidelines were provided. Appropriate strategies and tasks were outlined for each level in the program, though many of these activities are recycled in successive levels in the program in progressively more difficult contexts. Listening is often a mutual skill requiring spoken response from the listener, so the curriculum also takes a certain amount of time (approximately 20%) to be spent on speaking in the lab. There are different activities ranging recording one’s response to what is heard on the tape to taking off the headset and reconstructing information or comparing lecture notes in pairs or small groups. Individual instructors determine the sequence of activities each week, but what they do must be within the framework of the curriculum and the prescribed texts. The individualized listening lab is still retained. It becomes in the form of an optional open lab during lunch hour and after school. It is free for students needing additional practice and input to sign up for these hours. At intermediate and upper levels, teachers may also set aside one hour of the lab lesson a week for individual study or TOEFL practice. The article convinces that the communicative language lab with a well-defined curriculum and active teacher involvement is the most effective of all three approaches. This is judged from student evaluations and teacher response. What can lab activities do? Many people doubt that they can’t accomplish things as in a language lab as in a classroom with a tape or CD player. Actually, even the most basic features of a language lab enable students to participate in interactive information gap exercises that requires groups to listen to different information and then share, listen at their own pace, which results in less anxiety and a greater willingness to take risks, record and listen to their own responses, receive individual attention through random monitoring, and listen to superior sound quality. None of these activities can be done with just a tape or CD player in the classroom. “Lab activities should take advantage of the technology that that the lab system makes available, and the classroom does not.” (Stone, 1988, p.4) I think the tendency of utilizing technology to facilitate teaching listening is necessary and cannot be avoided. Making it effective and efficient is what we should do. In conclusion, we have to understand that the new directions in language learning and emerging new technologies will need to be examined for their potential contribution to more effective listening instruction. Reference: TESOL Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1(Autumn 1993) Teaching Listening in the Language Lab: One Program’s experience Judith Tanka