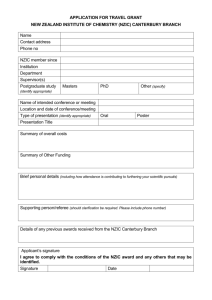

Summary of Stakeholder Content Water Quality

advertisement

Summary of Stakeholder (CWMOS) Content February 2009 WATER QUALITY Overview: 1) The current theme of ‘water quality’ is very broad and covers covers: - Drinking and domestic water quality and availability for both urban and rural communities - Waste management and the processing/recycling of storm/grey water, protection of water and waterways through land use/riparian management, water and waste treatment Stakeholder Sub-themes: 1) Drinking water for both urban and rural communities (for humans, stock and other biodiversity): a) purity or chemical composition (untreated and treated options, including recycling and biotic filtering techniques and ecosystems): particular focus on nitrates, nutrient levels, sediment levels, salinity and sea water encroachment on aquifers b) priority of availability for community use c) cost and equity issues between urban and rural communities d) economic/social value of the 100% pure reputation (bottling, tourism, heritage, identity) e) health and well being of consumers f) consumption of water in the atmosphere/chemical composition of the human body, medical implications g) piped municipal supply and/or drinkable quality of water in undesignated water bodies h) setting reasonable and achievable quality standards (possibly different standards for different categories of use) i) having equitable, aspirational quality standards, restoration of degraded sources 2) Water quality for other domestic uses for both urban and rural communities: a) purity or chemical composition (untreated and treated options, including recycling and biotic filtering techniques and ecosystems): particular focus on nitrates, nutrient levels, sediment levels, salinity and sea water encroachment on aquifers b) for food or beverage production, preparation and other (non-drinking) consumptive uses c) for personal hygiene, sanitation and health/medicinal uses d) for other domestic hygiene, sanitation uses e) for energy uses (heating, cooling etc) f) for all other domestic uses (some practical, some aesthetic, some relating to recreational/leisure use etc) g) for contact recreation in all water bodies 3) Water quality for agricultural use: a) purity or chemical composition (untreated and treated options, including recycling and biotic filtering techniques and ecosystems): particular focus on Page 1 of 4 nitrates, nutrient levels, sediment levels, salinity and sea water encroachment on aquifers b) for stock water c) for irrigation d) for sanitation and other regulatory functions 4) Water quality for non-agricultural commercial or industrial use: a) purity or chemical composition (untreated and treated options, including recycling and biotic filtering techniques and ecosystems): particular focus on nitrates, nutrient levels, sediment levels, salinity and sea water encroachment on aquifers b) for processing and manufacturing c) for hydrogeneration d) for housing developments e) for the urban corporate sector f) for community services – schools, hospitals, fire fighting etc 5) Managing water quality through land use (rural and urban)/riparian management (overlaps with land use control/regulation criteria): a) application of the polluter pays principle – through fines, rates, charges, other punitive measures, also incentives for conscientious pollution management b) use of funds obtained from polluters to finance restoration/enhancement and protection projects c) regulation and restriction (with associated monitoring/enforcement, compliance issues) of application of water, nutrients, fertilisers, stock effluent to land not directly adjoining water ways (non point source/diffuse discharges, contamination etc) d) regulation and restriction (with associated monitoring/enforcement, compliance issues) of stock movement, access to waterways, effluent management etc e) regulation and restriction (with associated monitoring/enforcement, compliance issues) of riparian and stream/infrastructure management, planting filter species, exclusion of stock, fencing, land set backs, control of didymo and other biotic contaminants etc f) monitoring, measurement and attribution of pollutants to individuals, groups, industry sectors etc g) regulation and restriction of housing, roading and other hard surface developments to minimise contamination from urban run-off h) regulation and restriction of community uses of chemicals, potential contaminants etc 6) Managing, processing and recycling waste and waste water (rural and urban): a) regulation and management of sewerage and other community waste systems b) regulation and management of storm water and drainage systems c) management, processing and re-use of grey water, rain water and storm water for designated uses (including irrigation, watering individual community gardens, some industry use etc); includes the installation/use of tanks and associated collection and processing infrastructure Recurring Stakeholder Perspectives: 1) a high quality of water was widely perceived as one of the environmentally and socially defining qualities of Canterbury, and essential not only to the health, wellbeing and identity of local people but also the maintenance of the 100% pure reputation and the continued national and international appeal of Canterbury as a destination for residence or visiting Page 2 of 4 2) an overwhelming majority of stakeholders believe that ensuring that there is sufficient community drinking water (and water for reasonable domestic use) which meets at least current drinking water quality standards without the need for further treatment should be an absolute bottom line and the number one priority for any management regime for Canterbury water. A very small minority of stakeholders feel that treatment is an acceptable option. 3) in some catchment areas there is a need to enhance current drinking water quality in order to restore it to its former high, untreated quality (eg. some rural communities); this is perceived as an inherent ‘right’ of all members of the community as it is a standard for the widespread, public good. Once again, a very small minority of stakeholders feel that treatment is an acceptable option. 4) it is almost universally asserted that domestic users should not have to ‘subsidise’ commercial (ie. for private economic gain) uses (at a much higher quantity per capita) by paying a charge/rate on their minimal (per capita) domestic uses; there is very strong opposition to the concept of charging for drinking water in particular, which is perceived as a fundamental human right, and where there is a very adequate local supply to meet these basic community needs if not overdrawn for commercial uses. A few vocal individuals argue that the entire community ought to ‘share’ the cost of water, with all users having to pay/cut back on use in times of shortage 5) it is universally accepted that water quality is essential to Canterbury ecosystems and associated biodiversity, it is not a purely human consideration 6) it is widely accepted that the high quality of Canterbury’s water and waterways is essential to the sense of pride and identity enjoyed by local people, as well as their sense of health and well being 7) it is also widely accepted that the high quality of Canterbury’s water and waterways is essential to the effective marketing of Canterbury as a destination for national and international tourists and thus has very real economic implications 8) it is widely acknowledged that water quality is essential to many cultural values (for example with respect to the mixing of waters and the inherent mauri or life force of NZ waters) and cultural practices such as mahinga kai, kaitiakitanga and the use of water in multiple cultures’ religious/spiritual/social practices 9) it is widely accepted that water quality is essential to the enjoyment of many social, recreational and tourism uses of water, particularly contact activities, in order that people feel safe and healthy and can enjoy the environmental aesthetics of clean water and healthy ecosystems 10) many stakeholders therefore emphasised the importance of a safe quality of water for the enjoyment of contact recreation and tourism activities in all Canterbury water bodies. A few also emphasised the desirability of natural water bodies being safe for drinking water, but most were satisfied with a contact standard for water bodies in proximity to developed areas (eg. Avon river, rural lowland streams etc). Many people sought the restoration of water bodies to pre-status quo standards (the early 1970s repeatedly cited as a more suitable ‘bottom line’) 11) it was often acknowledged that water quality is also important for certain commercial uses of water as impurities (for example didymo, mineral salts) can be seriously damaging to infrastructure or equipment or may compromise the use itself (viability of a crop, purity of a manufactured substance etc) 12) a majority of stakeholders feel that no further land use development initiatives should be permitted until there is objective, definitive scientific information publicly available Page 3 of 4 which demonstrates that these activities pose no risk to the quality of community drinking water supplies (application of the precautionary principle – absence of information demonstrating that they do pose a risk is no excuse for proceeding). Any contrary information should also be publicly available and accessible. On the other hand, a vocal minority of stakeholders feel that there is no need to delay or limit development initiatives because they believe that the scientific data is there to demonstrate that there is no risk to groundwater - but most are still unconvinced. 13) the management and limitation of land use intensification and of the application of water, nutrients etc and the enforcement of compliance with mandatory best practice measures or restrictions is universally accepted as pivotal to protecting Canterbury’s water quality 14) the management of land adjoining waterways and infrastructure and the enforcement of compliance with mandatory protection measures is also universally accepted as pivotal to protecting Canterbury’s water quality 15) a minority of stakeholders are confident that such best practice methods are adequate to address the protection of water quality from the impacts of land use intensification. Most stakeholders disagree, either because they do not accept that the measures themselves are adequate, or because they do not believe that the necessary compliance will occur. 16) a massive majority of stakeholders felt that the polluter pays principle ought to be applied absolutely, and reparation made to the wider community for any loss of water quality or amenity value. Further monitoring, attribution, enforcement and punitive measures are required, particularly as regards non-point source discharges. There was no dissent on this, although not all stakeholders addressed this point (so there may well be alternative views). 17) it was widely argued that funding for the management, preservation and restoration of water quality ought to be heavily subsidised by financial contributions from identified polluters. However there is also a role for voluntary, community groups (from both rural and urban communities) to be involved in both monitoring (‘policing’) and restorative activities 18) waste water management, processing and recycling are seen as community issues which need to be addressed by urban and rural communities at both a governance/infrastructure and at an individual level. Far more regulation, monitoring and enforcement measures are required with regard to individuals’ contributions to pollutant levels and individuals’ recycling and efficiency practices. There is also a strong perception that both rural and urban individuals need to take a lot more personal responsibility for sustainable practices at whatever level they are using water – from fixing leaking taps, to riparian management etc Page 4 of 4