Matteo Ricci and the Missionary Graveyard ( ) in Beijing

advertisement

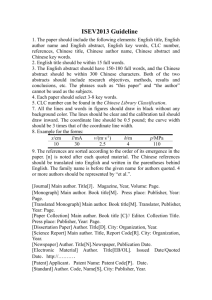

Matteo Ricci and the Zhalan Cemetery( 柵欄墓地) in Beijing Dr. Law Chi Lim, Robert It is a safe bet that many readers of this column are familiar with the name Matteo Ricci, especially those who have been associated in the past with the Wah Yan Colleges and Ricci Hall which are run by Jesuit priests. They probably also know that Matteo Ricci was a famous Jesuit missionary in China some hundreds of years ago. What they probably did not know (neither did I, until recently) is that Matteo Ricci’s tomb can still be found in Beijing. Some most unusual foreigners in China Matteo Ricci was born in 1552 in a noble Italian family and joined the Society of Jesus (耶穌會 ) in Italy at the age of 19 . When he was sent to China for missionary work by the society in 1582, he first went to Macao to study the Chinese language. For the next two decade he stayed mainly in Zhaoqing(肇慶) in Guangdong province and later in Nanjing (南京) where he befriended many Chinese scholars and important officials. The most prominent of these officials was Xu Guangqi (徐光啟) who was fascinated with Ricci’s rich knowledge of western astronomy, geometry, and trigonometry. Together, the two friends translated the Greek classic of Euclid’s Elements into Chinese (幾何原本). To the Chinese scholars, here was a foreigner unlike any one they had seen before---------this one was intelligent, cultured and fully conversant with classical Chinese. He translated many Chinese Confucian classics into Latin. In fact, it was him who coined the word Confucius as a name for the most venerated scholar in Chinese history. After he accurately predicted( while other Chinese astronomers failed) an eclipse of the sun on 22 September, 1596,his reputation spread further and he was subsequently granted an imperial audience with the Ming Emperor Wanli (萬曆 ) in 1601. He presented the emperor with many gifts which included maps of the world and a chiming clock. The Emperor was so impressed that he granted permission for Ricci to live and carry on his work in Beijing, something totally unheard of in the past. It must be said that Ricci developed a unique way to carry out his missionary work in China. Unlike other missionaries (like the Dominicans and Franciscans who were concurrently present in other parts of China), Ricci advocated complete adaptation to the Chinese culture. He even gave up his Catholic friar’s habit for that of a Chinese Confucian scholar. Because of his study of and respect for Chinese culture, he understood how Confucian beliefs, together with its tradition of venerating one’s elders and ancestors, formed the basis of Chinese social and political structures. So he established what was subsequently known as the ‘Ricci’s rules” which allowed his converts to continue with the traditional Chinese religious rites and ancestor worship. His method was to attract people to his church with western curiosities like chiming clocks and knowledge of western science and the spread of the Word of God became as if “incidental”. This proved to be the most effective evangelistic method given the practically “closed” society in China during the Ming Dynasty. By 1605 , there were more than 200 converts in Beijing , including many government officials like Xu Guangqi. Other Jesuit missionaries that came to China after Ricci’s death followed his rules faithfully and many of them were able to attain high positions in the Chinese Court . In fact , the Imperial Astronomy Department was led by Jesuit priests like Adam Schall von Bell ((湯若望) and Ferdinand Verbiest (南懷仁)for a period of nearly two hundred years covering the period from late Ming to early Qing Dynasty. They established a firm foundation for the spread of Christianity in China. The activities of the Jesuits in China did not go unnoticed in Rome which frowned upon Christians worshipping their ancestors. The Pope’s displeasure was further fuelled by the damaging reports sent home by the Franciscan and Dominican missionaries who were against the “liberal” ways of the Jesuits. It might well have been jealousy too because the former never achieved as much popularity in the Chinese court as the Jesuits. The final crunch came in 1705 during the reign of Emperor Kang Xi ( 康熙) when an emissary from Rome arrived in China to specifically forbid Christian followers in China to worship their ancestors. . The Emperor Kang Xi responded by issuing “certificates” (票) only to those missionaries who would declare that they would follow “Ricci’s rules” . Those who failed to comply were expelled from the country. This so-called “Rites Controversy” (禮儀之爭) continued over the next half century and fuelled periodic waves of anti-Christian incidences in Beijing as well as in other provincial centres. In spite of this , however, Jesuit priests with various scientific or artistic talents were still retained and treated with great respect in the court by emperors like Yong Zheng (雍正)and Qian Long (乾隆 ). The various priests were even allowed to be buried in Beijing after their death in the so called Zhalan Cemetery( 柵欄墓地). The Zhalan Cemetery When Matteo Ricci died in 1610 , the Emperor Wanli granted a piece of land outside the Fucheng gate of the west side of the old Beijing city wall for the priest’s body to be buried in --------- again another historical first for any foreign missionary in China. Subsequently, several hundred foreign missionaries (Jesuits as well as priests from other Orders) were buried in the nearby land and the area came to be known as the Zhanlan Cemetery. The graves were all marked by substantial stelae in Chinese style, and carved in Latin, Chinese, and sometimes Manchu characters. In 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion, the cemetery was destroyed, but rebuilt after several years at the demand of the foreign powers. The stone plaque which commemorates this event is still preserved in the present day cemetery. It was in effect a profuse apology from the Imperial Qing government to the dead priests. Since then, the cemetery suffered damages repeatedly at the hands of the Japanese army as well as the Nationalist army. No significant repair was done until the Beijing Municipal Bureau for Civil Affairs (北京市市委) acquired the land around the graveyard to build the Beijing Administrative College, which is, in effect, the training institution for Communist Party cadets in Beijing (中共北京市黨校). So the Zhanlan Cemetery is now situated in a very quiet corner inside this very exclusive place. As such , even people who had lived in Beijing for most of their lives may not know of the existence of this cemetery. However, during the Cultural Revolution, the red guards nearly destroyed all the tombstones if not for the ingenuity of the caretaker there who persuaded the youngsters to “bury” these tombstones so that the “foreign devils” would never be able to see the light of day. That was how the tombstones were preserved. Subsequently, the tombstones were dug up again and the Zhanlan Cemetery returned to its former glory. First time visitors to the cemetery are invariably impressed by the elegant lay-out of the graveyard. The impressive Stone Gate ( which dated from the time of Emperor Kang Xi) led to the main graveyard with the tombstone of Matteo Ricci in the middle flanked by two of his most famous colleagues----Adam Schall von Bell (湯若 望 ,1591-1666 ) and Ferdinand Verbiests (南懷仁, 1623-1688).The tombstones were ornate with carved dragons with 4 claws, one claw short of the 5 clawed-dragon which was generally reserved for the highest royalties). There were stone coffins behind each of the tombstones, but we had it from authority that they were just empty boxes. The actual remains of the priests were long gone and could not be recovered. Next to this main graveyard is another graveyard of similar size but simpler lay-out. It contains 60 tombstones of various foreign missionaries who died in China in the 16th to 18th century. These 63 tombstones have, in fact, witnessed over 300 hundred years of tumultuous history in China. One can spend hours admiring the stones and ruminating on the checkered history of these missionaries in China. Here are 63 men who felt the call to spread their religion, and no doubt, to save people’s souls, in this foreign and, perhaps, alien land. They opened China’s eyes to western science and technology. They did not set out to become an important part of the history of this strange land, but they did, and they never went home. Epilogue Matteo Ricci is often credited to be the first successful Christian missionary in China. But in fact, historically, Christianity had reached China in a big way during the Tang Dynasty, well before Ricci’s time. There is, in fact, a stone stele in the Xian Beilin (西 安碑林) Museum to prove it . But, of course, that is another story for another article.