Implementing a Post-Discharge Transition Care in

advertisement

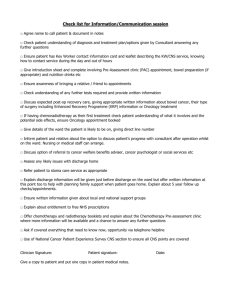

Integrated post-discharge transition care in a hospitalist system: disease-specific care and referral Chin-Chung Shu, M.D.1,2; Nin-Chieh Hsu, M.D.1,2; Yu-Feng Lin, M.D.1,2; Jann-Yuan Wang, M.D., Ph.D.2; Jou-Wei Lin, M.D., Ph.D.3; and Wen-Je Ko, M.D., Ph.D.1,4 Correspondence to: Wen-Je Ko, MD, PhD Department of Traumatology National Taiwan University Hospital No. 7, Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei 100, Taiwan E-mail: Kowj@ntu.edu.tw Tel: +886-2-23123456 ext 63098 Fax: +886-2-23952333 Running title: Post-discharge transition care in a hospitalist system Word count: Abstract-261; Main text-2145 Key words: Hospitalist, post-discharge transition care, Taiwan ____________________ 1Department of Traumatology, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei city, Taiwan 2Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei city, Taiwan 3Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Yun-Lin Branch, Yun-Lin county, Taiwan 4Department of Surgery, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei city, Taiwan 1 Abstract Background: The post-discharge period is a vulnerable time for patients with high rates of adverse events that may lead to unnecessary re-admissions, especially in older populations. Because care discontinuity is easily interrupted after hospitalist care hospitalist care, close follow-up may decrease re-admission. This study aimed to investigate the impact of an integrated post-discharge transition care (PDTC) in Taiwan’s hospitalist system. Methods: From December 2009 to May 2010, patients admitted to the hospitalist ward of a medical center in Taiwan, and discharged alive to home care were included. Under quality improvement initiative, an observation group was recruited in the first two months of the study period. Intervention of PDTC, including disease-specific care plan, telephone monitoring, hotline counseling, and hospitalist-run clinic visit were performed in the latter four months (intervention group). The primary endpoint was unplanned re-admission and death within 30 days after discharge. Results: There were 94 and 219 patients in the observation and intervention groups respectively. Both groups had similar characteristics on admission and discharge. In the intervention group, 18 patients who had worsening disease-specific indicators by telephone monitoring and 21 who reported 2 new/worsening symptoms by hotline counseling were associated with unplanned re-admission (p=0.031 and 0.019, respectively). Those who received PDTC had lower rates of re-admission and death within 30 days post-discharge than the observation group (15% vs. 25%, p=0.021). No-use of hospitalist-run clinic and presence of underlying malignancy were other independent factors for 30-day post-discharge readmission and death. Conclusion: The integrated PDTC using disease-specific care, telephone monitoring, hotline counseling and a hospitalist-run cliniccan reduce post-discharge readmissions and deaths. 3 Introduction The hospitalist system has grown worldwide in recent decades.1-3 even though its pros and cons are still under debate. While the hospitalist system may save on hospitalization costs, a major concern is interruption of patient care w provided by the primary care physician.4 In fact, short-term post-discharge re-admission rates are very high in the elderly, approaching 20% within one month after discharge.5 Reasons for this include poor compliance, instability of chronic disease, and insufficient communication between in- and out-patient physicians.6 Home visits and telemedicine have been studied in post-discharge care, but the reports are limited to those with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or post-surgery. 7-9 In a particular referral center, the one-month re-admission rate after discharge from the hospitalist ward is 22% (unpublished data). Based on a concept of care transition intervention,10 post-discharge transition care (PDTC) is important in extending the care continuity after discharge from a hospitalist ward.11-12 Close follow-up and communication may prevent adverse events and decrease re-admission rates before the primary care physician takes over care continuity.13 4 Although the experience of post-discharge transition care (PDTC) has been studied extensively, the integrated model using telephone service has not been well studied in a hospitalist system.10, 14 Given the success of care transitions in decreasing post-discharge adverse events and reducing re-admission rates,10 this study aimed to investigate if a comprehensive PDTC program consisting of establishing a disease-specific care plan on discharge, a daily patient hotline, scheduled follow-up calls, and a hospitalist-run clinic can reduce re-admission rates and post-discharge mortality. 5 Methods Study subjects This prospective study was conducted in National Taiwan University Hospital, a tertiary-care referral center in northern Taiwan, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the hospital (200900012023R). From December 2009 to May 2010, all patients >18 years old and admitted to the hospitalist-care ward from emergency department were consecutively screened. Those who were discharged alive to home were enrolled them according to the designated general medical diseases (Table 1). The disease-based sub-groups were clearly monitored by specific care plans. Other inclusion criteria included a telephone line at home and caregiver/patient who could speak Chinese or Taiwanese language. Patients were excluded if they were electively admitted, previously enrolled, died during hospitalization, transferred to a subspecialty ward or other institutions, refused consent, or had an anticipated life expectancy <30 days. Patients without underlying chronic illness and a Barthel score >60 were also excluded for presumably not requiring monitoring.15 For quality improvement initiative during the first two months of study period, the patients received no other active intervention except a follow-up 6 call 30 days after discharge to confirm the patient’s status of readmission, emergency department visit, and survival (observation group). In the latter four months of the study, the patients received integrated PDTC within 30 days after discharge (intervention group). For every patient, the hospital doctors made a discharge plan. The ward staff educated the patients and their caregivers regarding the usual discharge care plan, which included chest care, inhaler use, tube/wound care skills, diet/drug compliance and other disease-specific elements of discharge teaching. Caregivers were taught if the patients were illiterate or had cognitive deficits or Barthel score <35. The patients were referred back to the clinic of theirprimary care physician for continuity of care. A primary care physician was defined if the patient had visited the same doctor three times or more within one year prior to admission.4 If there was no primary care physician, the patients were followed-up at the hospitalist-run clinic. Integrated PDTC protocol For the intervention group, the study nurses and hospital physician made a PDTC plan, which consisted of a disease-specific care plan, scheduled follow-up calls, and a hotline in order to monitoring disease status and their 7 indicators (Table 1) aside from the usual discharge care plan. The disease-specific indicators were initially chosen and then modified by their hospital care physician according to the patient’s condition.16 The study nurses and physicians explained and educated the patients and their caregivers as regards measuring and reporting the indicators, and adhering to the discharge plan and medication use. After discharge, the study nurse contacted and cared for the patients regularly by telephone on post-discharge days 1, 3, 7, 14 and 30. Using a standardized case report form, the content of telephone calls service included: 1) monitoring disease-specific indicators; 2) enhancing drug compliance; and 3) confirming adherence to the discharge care plan, including diet/life modification and tube/wound care skill. A designated telephone line was also opened from 8am to 9pm daily for call-in counseling for the intervention group. Once there was disease worsening found (see online supplement), the study nurses reported to and discussed with the subject’s hospitalist for further management. Our ward clinic was opened between 8AM and 9PM daily and managed by a hospitalist. Clinical characteristics The study patients’ clinical characteristics, laboratory data, hospital course 8 and outcomes were recorded. The Charlson index and Barthel scores were calculated as in previous studies.17-18 Patients were followed up for 30 days after discharge or until death, re-admission or loss of follow-up. Loss of follow-up was defined if the patient/caregiver could not be contacted for two consecutive two times. The primary endpoint was unplanned readmission and unexpected death within 30 days after discharge. Secondary endpoints included unplanned visits to the emergency department (ED) or hospitalist-run clinic. An urgent or unplanned clinic visit was defined as <24 hours duration from appointment to clinic visit. Statistics analysis Inter-group differences were compared by independent t test for numerical variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Curves of probability of re-admission and death were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression was used to identify factors associated with 30-day primary outcome by forward conditional method. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using the SPSS (Version 13.0, Chicago, IL). 9 Results From December 2009 to May 2010, a total of 2932 patients were admitted to general ward from the emergency department. Of the 737 patients who were admitted to the hospitalist ward, only 551 were discharged alive for home care (Fig. 1). Of them, 139 patients did not match the enrolment diseases, 95 declined to join, and 4 were defined as “not requiring PDTC”. Among the 313 patients finally enrolled, 94 patients were recruited into the observation group and 219 into the intervention group with PDTC. The clinical characteristics were similar between the two groups including age, gender, underlying comorbidities, and presence of a primary care physician (Table 2). Results of laboratory examinations on admission were also similar. Upon discharge, the patients in the observation group were most frequently cared for by their children (40% vs. 27%, p=0.009) whereas those of the intervention group were commonly cared for by their spouses (42% vs. 31%, p=0.084). Both groups had comparable activity of daily living by Barthel scores, length of hospitalization, and defined diseases (see online supplement). Extraordinary care including tubes (e.g. nasogastric tube, tracheostomy tube, and draining tube), catheters (e.g. Foley catheter, catheter for dialysis, and 10 draining tube), was similar between the two groups. Wounds, mostly bedsores, which needed regular cleaning and dressing at home were noted in 11.8% of the study patients. In the post-discharge course, 843 calls were recorded, with an average of 6.10 ± 2.96 minutes per call. Among 219 patients receiving PDTC, 134 received all of the calls and the remaining 85 were terminated earlier, including 53 lost to follow-up and 32 re-admissions/death. Eighteen had worsening disease-specific indicators, six of whom were referred to the ED and 12 to the clinic appointments (only 2 attended the hospitalist-run clinic). Six (five from the ED and one from the clinic) were re-admitted within 30 days after discharge. Those with worsening indicators had significantly higher risk of re-admission than those without (p=0.031 by the Fisher’s exact test). Another four cases had wrong tube or wound care that was corrected after further education. All patients except two had good drug compliance. Forty-four (20%) patients in the intervention group contacted us 105 times through the designated telephone line. Of them, 29 calls from 21 patients reported new or worsening symptoms. Four were referred to the ED and 11 to the outpatient clinic, while the remaining six had counseling only. Seven (33%) were re-admitted (4 from the ED and 3 from the clinic). Those reporting new or 11 worsening symptoms had higher risk of re-admission than those without new or worsened symptoms (p=0.019, Fisher’s exact test). The other 76 patients with counseling all asked for minor medical help such as health education, skill confirmation, and drug/diet consultation. In terms of post-discharge clinic appointment, there were more scheduled appointments at the hospitalist-run clinic, either regular (27% vs. 14%, p=0.008) or unplanned visits (9% vs. 2%, p=0.005) and less with the primary-care physician (72% vs. 83%, p=0.038) in the observation group than in the intervention group. Visits of the hospitalist-run clinic were associated with less re-admissions (p=0.088) than no visits, whereas that of the primary care physician clinic were not significant (p=0.890). The numbers of ED visits were not different between the observation and intervention groups (23% vs. 17%, p=0.212). Within 30 days after discharge, the observation group had significantly higher rates of re-admission and death than the intervention group (25% vs. 15%, p=0.021, Fig. 2). Further analysis revealed that the observation group had borderline higher re-admission rate (22% vs. 14%, p=0.075) and significantly higher death rate (3% vs. 1%, p=0.048). In contrast, the re-admission rate of the overall patients in the general wards of the hospital 12 were similar during the observation and the intervention periods (17.0% vs. 17.2%, p=0.913, chi-square test; see online supplement). Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression revealed three independent factors for primary outcome within 30 days after discharge, including underlying malignancy (HR: 2.34, 95% CI: 1.33~4.11), not visiting the hospitalist-run clinic after discharge (HR: 2.65, 95% CI: 1.04~6.73), and not receiving PDTC (HR: 2.05, 95% CI: 1.16~3.65) (Table 5). Artificial tubes and catheters, wounds requiring dressing change, age >65 years, Barthel score <60, and longer hospitalization stay (≥14 days) were not associated with post-discharge re-admission and death. 13 Discussion This study investigates experiences with a multi-faceted PDTC program consisting of a disease-specific care plan, follow-up phone calls, and referral to a hospitalist-run clinic to decrease 30-day re-admissions and mortality. In addition to the outpatient clinic, a PDTC program is important for patients after discharge. Absence of underlying malignancy and visits to the hospitalist-run clinic are also associated with better outcome. The best method of care transition after discharge has not been well-established, although several modes have been studied including telephone-call follow-up, telehealth communication and monitoring and home visits by nursing staff.8, 19-21 A integrated PDTC program using telephone-call follow-up is easy to implement and has minimal equipment requisites.20 The telephone service in the current study included active regular contact, to detect disease worsening earlier, and stand-by counseling service.8 In addition, the service monitors patient medication compliance and lifestyle modifications.22 The standby counseling service was also helpful, especially for care related questions and unpredicted events.23-24 However, the number of ED visits is not significantly reduced, probably because the service is only available from 8am to 9pm, and some aspects of the ED are irreplaceable. 14 The findings in the current study suggests that outpatient clinics run by hospitalists may play important roles in improving post-discharge outcomes.11 Outpatient follow-up by a hospitalist that is familiar with the patients’ disease status can provide continuous care for discharged patients and complements the PDTC. Extraordinary hospitalist care after discharge is very important, because 20~30% of patients do not have a primary care doctor. As such, the frequency of hospitalist-run clinic visits in the study increases in those without PDTC and decreases in the intervention group. Continuity of post-discharge patient care can be transitioned and covered by an integrated PDTC and hospitalist-run clinics. The study has several limitations to our study. First, the study used quality improvement initiative design without randomization. This may not be a serious concern because of the similarity in clinical characteristics among the two study groups and in the re-admission rate of patients discharged from the general wards. Second, telephone monitoring may be biased by the patient or caregiver’s expression. Third, in a multi-faceted PDTC, it is hard to distinguish where the strength comes from which piece of intervention. Fourth, the number of patients excluded is considerable and may bias the result. Lastly, because this study was performed in a tertiary referral center and the patients had 15 multiple co-morbidities, the results cannot easily be generalized to the regional or district hospitals. The hospitalist system has become widely accepted in recent decades,25 with advances developed to cope with any discontinuity from in-patient to out-patient care.3, 12 However, hospitalist PDTC guidelines are lacking at present. Apart from discharge summary and planning,6, 26-27 the current study shows that an integrated PDTC is effective in care transition and may be applied to general medical patients, who require an ever-increasing amount of resources within the currently ageing society.28-29 16 Competing Interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Authors’ Contributions Dr. W.J. Ko designed the study. Drs. C.C. Shu, N.C. Hsu, and Y.F. Lin were involved in the project execution, clinical data collection, analysis and the manuscript writing. Dr. J.W. Lin also participated in data analysis and J.Y. Wang contributed to manuscript writing. Acknowledgements The authors thank the support of research assistants from the Ministry of Economic Affairs (program number 98-EC-17-A-19-S2-0134). 17 REFERENCES 1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of "hospitalists" in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996 Aug 15;335(7):514-7. 2. Peterson MC. A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 Mar;84(3):248-54. 3. Kuo YF, Sharma G, Freeman JL, et al. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 12;360(11):1102-12. 4. Sharma G, Fletcher KE, Zhang D, et al. Continuity of outpatient and inpatient care by primary care physicians for hospitalized older adults. JAMA. 2009 Apr 22;301(16):1671-80. 5. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 2;360(14):1418-28. 6. van Walraven C, Taljaard M, Bell CM, et al. A prospective cohort study found that provider and information continuity was low after patient discharge from hospital. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010 Sep;63(9):1000-10. 7. Young L, Siden H, Tredwell S. Post-surgical telehealth support for 18 children and family care-givers. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(1):15-9. 8. Wakefield BJ, Ward MM, Holman JE, et al. Evaluation of home telehealth following hospitalization for heart failure: a randomized trial. Telemed J E Health. 2008 Oct;14(8):753-61. 9. Sorknaes AD, Madsen H, Hallas J, et al. Nurse tele-consultations with discharged COPD patients reduce early readmissions--an interventional study. Clin Respir J. 2011 Jan;5(1):26-34. 10. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep 25;166(17):1822-8. 11. van Walraven C, Mamdani M, Fang J, et al. Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Jun;19(6):624-31. 12. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, et al. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007 Sep;2(5):314-23. 13. Lungen M, Dredge B, Rose A, et al. Using diagnosis-related groups. The situation in the United Kingdom National Health Service and in Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2004 Dec;5(4):287-9. 19 14. Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Effect of a nurse team coordinator on outcomes for hospitalized medicine patients. Am J Med. 2005 Oct;118(10):1148-53. 15. Leong IY, Chan SP, Tan BY, et al. Factors affecting unplanned readmissions from community hospitals to acute hospitals: a prospective observational study. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009 Feb;38(2):113-20. 16. Anthony S. Fauci EB, Dennis L. Kasper, Stephen L. Hauser, Dan L. Longo, J. Larry Jameson, and Joseph Loscalzo, Eds. . Harrison's PRINCIPLES OF INTERNAL MEDICINE. 17 ed: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2008. 17. Wang HY, Chew G, Kung CT, et al. The use of Charlson comorbidity index for patients revisiting the emergency department within 72 hours. Chang Gung Med J. 2007 Sep-Oct;30(5):437-44. 18. Sainsbury A, Seebass G, Bansal A, et al. Reliability of the Barthel Index when used with older people. Age Ageing. 2005 May;34(3):228-32. 19. Chow SK, Wong FK, Chan TM, et al. Community nursing services for postdischarge chronically ill patients. J Clin Nurs. 2008 Apr;17(7B):260-71. 20. Braun E, Baidusi A, Alroy G, et al. Telephone follow-up improves patients 20 satisfaction following hospital discharge. Eur J Intern Med. 2009 Mar;20(2):221-5. 21. Kleinpell RM, Avitall B. Integrating telehealth as a strategy for patient management after discharge for cardiac surgery: results of a pilot study. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007 Jan-Feb;22(1):38-42. 22. Cook PF, McCabe MM, Emiliozzi S, et al. Telephone nurse counseling improves HIV medication adherence: an effectiveness study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009 Jul-Aug;20(4):316-25. 23. Cook PF, Emiliozzi S, McCabe MM. Telephone counseling to improve osteoporosis treatment adherence: an effectiveness study in community practice settings. Am J Med Qual. 2007 Nov-Dec;22(6):445-56. 24. Butz A, Kub J, Donithan M, et al. Influence of caregiver and provider communication on symptom days and medication use for inner-city children with asthma. J Asthma. 2010 May;47(4):478-85. 25. Lee KH. The hospitalist movement--a complex adaptive response to fragmentation of care in hospitals. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008 Feb;37(2):145-50. 26. Ling Wang Y-ML, Se-Chen Fan, Wei-Tzu Chao. Analysis of Population Projections for Taiwan Area: 2008 to 2056 Taiwan Economic Forum. 21 2009;7(8):36-69. 27. Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould CL, et al. The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA. 2004 Jun 2;291(21):2616-22. 28. Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, et al. CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003 Jul;13(3):176-81. 29. Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, et al. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999 Jul;54(7):581-6. 30. Stinson JN, Kavanagh T, Yamada J, et al. Systematic review of the psychometric properties, interpretability and feasibility of self-report pain intensity measures for use in clinical trials in children and adolescents. Pain. 2006 Nov;125(1-2):143-57. 22 Table 1. Disease-associated indicators designated for post-discharge care by telephone-call follow-up Disease Indicator 1 Indicator 2 Indicator 3 CHF with acute exacerbation Body weight Leg edema* Dyspnea index† Liver cirrhosis with decompensation Body weight Consciousness COPD with acute exacerbation Fever Dyspnea index† DM with poor control Blood glucose Hypertension with poor control Blood pressure Acute on chronic renal failure Body weight Urine output Terminal cancer Consciousness Pain scale# Ischemic stroke Barthel’s score Consciousness UGI bleeding Stool character Heart rate Pneumonia Fever Dyspnea index Urinary tract infection Fever Dysuria Cellulitis Size of lesion Local pain# Intra-abdominal infection Fever Abdominal pain# Chronic disease with acute change Sputum character Dyspnea index† Acute illness Fever Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, Diabetes mellitus; UGI, upper gastrointestinal *measured by grading developed for cancer treatment30 †measured by the Medical Research Council dyspnea scale 31 #measured by the Numerical Rating Scale32 23 Table 2. Clinical characteristics and laboratory data on initial admission compared between the observation and intervention groups Observation group (n=94) Intervention group (n=219) p value Age, years 71 ± 15 69 ± 16 0.207 Gender, Male 42 (45) 115 (53) 0.204 3.5 ± 3.2 3.1 ± 3.1 0.210 Primary care physician, presence 66 (70) 173 (79) 0.094 Underlying malignancy 30 (32) 57 (26) 0.287 10079 ± 5011 10903 ± 5588 0.232 Hemoglobin, g/dL 13.2 ± 18.3 11.2 ± 2.6 0.228 Creatinine, mg/dL 2.6 ± 5.1 1.9 ± 2.0 0.284 Albumin, g/dL 3.4 ± 0.4 3.3 ± 0.8 0.630 38 (40) 58 (27) 0.009 3 (3) 5 (2) 0.617 Spouse 29 (31) 92 (42) 0.084 Non-relative caregiver 21 (22) 62 (28) 0.321 Barthel score at discharge 62 ± 35 66 ± 37 0.378 Length of hospital stay, days 8.5 ± 8.0 8.9 ± 6.1 0.660 Artificial tube/catheter at discharge 22 (23) 51 (23) 0.982 Wound needing change dressing 10 (11) 27 (12) 0.671 Charlson Score Laboratory data at the initial admission Leukocyte count, /µL Care-giver at home Child generation Parental generation Data are no. (%) or mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise indicated. 24 Table 3. Multivariate analysis for factors possibly associated with re-admission and unexpected death within 30 days after discharge Multivariate Characteristics p value Age: years ≥ 65 HR (95% C.I.) 0.980 < 65 years Gender Male 0.423 Female Artificial tube/catheter At least one 0.880 None Wound needed change of dressing Presence 0.404 Absence Charlson score Barthel score at discharge <2 2~4 0.580 >4 0.418 < 60 0.208 ≥ 60 Primary care physician Presence 0.710 Absence Underlying malignancy Yes 0.003 2.34 (1.33 ~ 4.11) No Length of hospital stay < 14 days 0.188 ≥ 14 days Blood leukocyte count (/µL) 6000 ~ 11000 0.494 < 6000, >11000 Post-discharge transition care Not received 0.014 Received Post-discharge disease item Chronic illness Acute illness 25 0.172 2.05 (1.16 ~ 3.65) Visit of integrated clinic by hospital physician Not received 0.041 Received Care-giver at home Not spouse Spouse 26 0.465 2.65 (1.04 ~ 6.73) LEGEND Figure 1. Flow chart of patient enrolment: “Not required”, patients with no chronic illness and Barthel score ≥60; “Dx, not matched”, patient’s diagnosis did not match the enrolled disease items; “Patient refused”, patient refused enrolment Figure 2. The probability of re-admission and unexpected death within 30 days after discharge was plotted by the Kaplan Meier method and compared using log-rank test. PDTC, post-discharge transition care 27