LRC - The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong

advertisement

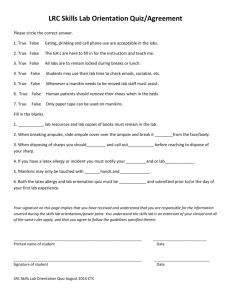

The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong 2013 Mission To identify appropriate topics for potential law reform projects; To facilitate the high-quality, objective and independent study of topics so identified, with a view to considering and, if appropriate, putting forward law reform proposals for consideration by the Administration, the relevant stakeholders and the community at large; To engage the public in the law reform process by publication of relevant materials, effective communication with the community and public consultation; To monitor the implementation of law reform proposals; To ensure that, through the law reform process, the laws of Hong Kong can meet the needs of the community and can stay in the forefront of international or regional development. 1 Foreword This is the first review of the work of the Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong (LRC) since I took office as Secretary for Justice and became its Chairman on 1 July 2012. This review, which covers the period from 1 January 2011 to 30 June 2013, provides an overview of the LRC’s current projects and the progress during the past years. The year 2012 marked the 32nd anniversary since the LRC was established in 1980. Over that period of time, a total of 72 members of the community have served as members of the LRC and a further 462 on one or more of the LRC’s sub-committees. It is the input of their skills, expertise and experience which make the reform proposals of each LRC project so uniquely valuable. A list of the current members of the LRC and its sub-committees as at 30 June 2013 is set out at the Annex. Law reform plays an important role in any society which aspires to maintain the rule of law. As our society evolves, our laws have to change to meet the needs of the society. Indeed, unless our laws are kept up-to-date, the risk of injustice and unfairness is likely to emerge. The aim of any LRC project is to consider the law in a specified area and, where appropriate, present wellconsidered proposals for improving our law. While the process of carrying out a LRC review of any area of law is itself beneficial in that it stimulates public debate and awareness, the ultimate purpose is to offer suggestions for reform so as to improve our law. It is important for the health of our legal system that the LRC’s reform proposals are given full and timely consideration and, where thought appropriate, implemented as soon as practicably possible. As Chairman of the LRC, not only do I place emphasis on choosing appropriate topics for consideration, I have made efforts to impress upon the relevant Government policy bureaux or departments the importance of responding to LRC reports and of speeding up their consideration and implementation. In terms of implementation of reports generally, we now have two mechanisms to ensure that there will be effective and timely followup by the Administration on the LRC’s recommendations. The first is a set of Guidelines issued by the Administration in October 2011 requiring bureaux or departments to provide public responses to LRC’s reports under their purview within specific time limits. Pursuant to these Guidelines, a detailed response should be given within 12 months of the publication of a LRC report, setting out which recommendations the Administration accepts, rejects or intends to implement in modified form. Even before that time, the relevant bureaux should issue within 6 months of a report’s publication an interim response, setting out a clear timetable for implementation and the steps taken so far. The other mechanism was introduced in March 2012 by the House Committee of the Legislative Council (LegCo). Under this mechanism, the Secretary for Justice will submit an annual report to the Administration of Justice and Legal Services Panel (AJLS Panel) of the LegCo addressing the progress on those reports which have not yet been implemented. This new reporting process is to facilitate the AJLS Panel and other relevant LegCo panels to follow up on 2 progress of law reforms with the relevant bureaux and departments. With regard to reports that have been implemented since 2012, I am pleased to report that in January 2012, the Guardianship of Minors (Amendment) Ordinance 2012 was enacted to implement the recommendations of the Guardianship of Children report, published in 2002. In July 2012, the report on The Common law Presumption that a Boy under 14 is Incapable of Sexual Intercourse, published in 2010, was implemented by the Statute Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Ordinance. Further, in July 2012, the Residential Properties (First-hand Sales) Ordinance was enacted. This legislation has implemented, in part, the recommendations in the LRC’s reports on descriptions of flats on sale published in 1995 and 2002, on local uncompleted residential property and local completed residential property respectively. Last but certainly not least, I would like to express my gratitude to all those who have participated in the work of the LRC over the last two years, either by serving as members of the LRC or of one of its sub-committees, or by responding to the consultation papers the LRC has published. I would also like to take this opportunity to thank each of the colleagues of the LRC Secretariat for their dedication and able assistance. The road of law reform is never short of challenges, but the LRC will do its utmost to achieve its mission. Rimsky Yuen, SC, JP Secretary for Justice Chairman of the Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong 30 June 2013 3 The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong (LRC) Prior to the establishment of the LRC in 1980, there had been a number of formal and informal committees and groups which had considered various aspects of law reform. The first permanent machinery for law reform in Hong Kong may be traced back to the Law Reform Committee, which was established by the then Governor on 16 March 1956. Its terms of reference were restricted, however, to examining legislations enacted in the United Kingdom having regard especially to the reports of the Law Reform Committee appointed by the Lord Chancellor on the 16 June 1952. That Committee issued five reports during the period between 1957 and 1964, when it ceased to operate. In 1965, a Law Reform Drafting Unit was formed in the then Attorney General’s Chambers. It primarily dealt with the drafting of approved law reform measures and to a lesser extent, identifying UK legislative measures that were suitable for adoption in Hong Kong. The Unit was, however, not in a position to propose wider reform of the law. In the late 1970s, a group of 14 lawyers drawn from the Government and the private sector formed an informal law reform committee under the chairmanship of a High Court Judge, the then Mr Justice T L Yang. The arrival of a new Attorney General in Hong Kong in 1979 addressed calls for a more formal mechanism for law reform. In January 1980, the Chief Justice and the Attorney General presented to the Executive Council (ExCo) their joint views as to how law reform should be handled in the future. Their recommendation that the LRC should be established was endorsed by the ExCo on 15 January 1980. The initial membership of the LRC consisted of the Attorney General (as Chairman), the Chief Justice and the Law Draftsman (all as ex officio members) and eight other unofficial members drawn from five categories: (a) a member of the HK Bar Association; (b) a member of the HK Law Society; (c) two members of the School of Law of Hong Kong University; (d) two unofficial members of the ExCo or Legislative Council (LegCo); and (e) two or more other members. It was envisaged that the last two categories would allow the appointment of non-lawyers to the LRC, which from the outset was seen as an important element in the LRC’s composition. The three ex officio members were entitled to have their places occupied by a representative and, in the Chief Justice’s case, a member of the High Court was specifically named as representative. The inclusion of the Law Draftsman as an ex officio member was intended to provide the LRC with access to law drafting expertise, 4 enabling the inclusion of draft legislation in the LRC's reports where appropriate. Apparently, the rationale for the structure and membership proposed for the LRC was that it built on existing expertise and could be established speedily with few resource implications. The LRC today differs in a number of aspects from the model drawn up in 1980. Perhaps the most significant change relates to its membership, although a flexible approach has been adopted from the outset. Early in its life, the Chief Justice's representative morphed into a separate permanent seat on the LRC in addition to the Chief Justice, first as a High Court or Court of Appeal judge and later, since 1997, as a judge of the Court of Final Appeal. In contrast, neither the Attorney General or since 1997, the Secretary for Justice nor the Law Draftsman have availed themselves of the opportunity to appoint a representative in their stead, other than occasionally the individuals who have been temporarily acting in their posts. With the establishment of law schools at City University and the Chinese University, the academic lawyers on the LRC are no longer restricted to those from the University of Hong Kong. Over the years, the community had expressed reservations concerning the inclusion of members of the ExCo or Legislative Council (LegCo). Amongst others, there was the concern that their inclusion runs the risk of a perception of politicisation of the LRC, with the concomitant difficulty of avoiding the appearance of favouring one political party over the others. The last occasion on which a serving member of the ExCo was appointed to the LRC was in 1989 and the most recent appointment of a serving member of the LegCo was in 1999.1 All members of the LRC, other than the three exofficio ones, are appointed by the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. On the operational level, the LRC initially operated by having lawyers from the Attorney General's Chambers to serve as part-time secretaries to the subcommittees set up to work on each topic. That was found unsatisfactory because of the competing demands on the secretaries' time. Support is now provided by lawyers in the Department of Justice who work full-time in the LRC's Secretariat. At the same time, not every LRC project requires the setting up of a sub-committee. In a number of instances, the LRC has itself undertaken the reviews without the involvement of a sub-committee, by way of a fast-track with a view to speeding up the reform process.2 Another change is that references can now be made to the LRC by either the Secretary for Justice or the Chief Justice, rather than requiring joint referrals, but this has had no practical effect as every reference to date has been made by both of them. 1 LegCo member Hon Sophie Leung was appointed to the LRC in September 1999 and served till August 2005. Hon Maria Tam, who was then a member of both ExCo and LegCo, served from June 1989 to June 1992. ExCo member Hon Anna Wu served as a member from January 2006 to December 2011, whose appointment to ExCo came after appointment to the LRC. 2 Examples include projects reviewing aspects of the law relating to enduring powers of attorney and proposing the abolition of the "year and a day" rule in homicide. 5 The end product of each LRC project is a published report which reviews the relevant area of Hong Kong law and, where appropriate, sets out recommendations for reform. Those recommendations are the result of detailed analyses and deliberations, and invariably include a comparative study of the relevant laws in other jurisdictions and a careful consideration of any comments received from the public on the initial consultation paper. The range of subjects which the LRC has considered is wide. The topics so considered and a detailed progress report on implementation of the LRC reports can be found on the LRC’s website: http://www.hkreform.gov.hk The LRC’s strengths The particular strengths of the LRC include: it is independent, and presents its recommendations after an objective examination of the relevant laws; its members come from a wide range of backgrounds, enabling the LRC to consider possible reform of the law from the macro perspective of the community as a whole, rather than solely from that of the legal profession or any specific sector; its secretariat is manned by full-time professional staff of the Department of Justice; it involves the general public in the reform process by consulting as widely as possible before reaching final conclusions on any of its references; all reports and consultation papers are published and made freely available to the public, both in hard copy and on the internet. While the LRC is not the only source of proposals for law reform in Hong Kong (for instance, proposals for reform may be generated by Government bureaux or departments), the LRC’s role is unique where the subject: does not fall readily under the responsibility of one particular bureau of the Government (for example, reform of the law of privacy); raises issues which are outside the Government’s day to day activities (for example, reforming the rules for determining domicile); and requires the dedication of full-time legal input to conduct a review (for example, the review of insolvency law). In such cases, it is unlikely that reform of the relevant areas of law would be achieved without the involvement of the LRC. 6 From left to right (front) Mrs Eleanor Ling; Mr Paul Wan; Hon Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma, CJ; Hon Rimsky Yuen, SC, SJ; Hon Mr Justice Tang, PJ; Prof. Michael Wilkinson; (back) Mr Anderson Chow, SC; Mr Eugene Fung, SC; Ms Angela Lee; Mr Peter Rhodes; Mrs Pamela Chan; Mr John Budge; Mr Stephen Wong. Criteria for referral to the LRC The Secretary for Justice or the Chief Justice decide which aspects of the law should be referred to the LRC for consideration. In practice, topics for reform are normally decided jointly by them or at LRC meetings. These will normally be chosen from suggestions made by the Administration, members of the LRC, the legal profession or the public at large. To assist the Secretary for Justice and the Chief Justice, the LRC Secretariat from time to time collates suggestions for reform projects and presents them for their consideration. Since its establishment in 1980, the LRC has considered a wide variety of topics of varying complexity and breadth. There are no hard and fast rules as to which topics are suitable for referral to the LRC, but a number of factors will usually be considered by the Secretary for Justice and the Chief Justice: Is there a general problem or shortcoming in the relevant area of law ? The problem or shortcoming should be a general one, and not one which relates only to a particular individual or a specific case. Are the issues raised more ones of policy than law? As a broad rule of thumb, a subject is not likely to be best suited for consideration by the LRC if the issues it raises are essentially ones of Government policy, rather than law or legal policy. While it would be unlikely, for instance, that the LRC would consider questions of taxation or immigration, as these are areas where Government policy concerns predominate, that does not mean that the LRC could not consider the general policy issues raised in respect of a subject such as the legal age of majority. Could the subject be more effectively considered elsewhere? Where there is a specialist body with expertise in the particular area of law in question, then the subject is unlikely to be referred to the LRC. 7 For instance, the Standing Committee on Company Law Reform, or the Court Users’ Committees, would be better placed than the LRC to consider company law or court procedural matters respectively. Is there a realistic prospect of implementation? The purpose of the LRC’s work is to improve the law. Its resources are limited, and it would be wasteful of those resources to embark on a project if it was unlikely that any resulting proposals could be implemented. The LRC would therefore be unlikely to consider an area of law where the Administration had clearly indicated that it saw no need for change. In addition to these factors, the Secretary for Justice and the Chief Justice need to consider the questions of timing and availability of resources, and decide when the LRC is able to take on a new project. How the LRC works The first step in proposing a reference to the LRC for deciding whether a subject should be studied is the preparation of a background research paper by the lawyers who serve full-time in the LRC Secretariat. This paper will then form the basis for discussion and deliberation by a sub-committee of experts, where members of the LRC also decide that a sub-committee should be set up to examine the subject. Members of the sub-committee are appointed by the Chairman of the LRC. In appropriate cases, the LRC may decide to dispense with a sub-committee and to consider the matter itself by way of a fast-track approach on the basis of the Secretariat’s research analyses and findings. Whether or not a sub-committee is appointed to deal with a particular subject, the LRC always strives to ensure that there is extensive public consultation on any of its projects before it reaches its conclusions. In almost every case, the views of the relevant stakeholders and the public will be sought by way of a consultation paper, which sets out the preliminary conclusions and recommendations. The publication of consultation paper is widely publicised, and the paper is made available to the public both in hard copy and on the LRC’s website. During the public consultation period, members of the subcommittee and the Secretariat will often be asked to provide briefings on the proposals to the relevant Panels of the LegCo and organisations interested in the subject. The responses to the consultation paper play a crucial part in assisting the LRC to finalise its proposals. Once completed, the sub-committee's report is passed to the LRC for consideration. The LRC considers the sub-committee’s report in detail, assisted by the chairman and members of the sub-committee, before issuing a final LRC report. Reports are generally published simultaneously in English and Chinese, and both in hard copy and on the LRC’s website. Where the subject is likely to be of general public interest, one or more members of the LRC or the relevant sub-committee will present the report at a press conference to bring the report to the public's attention. After publication, the 8 report containing all the LRC’s recommendations on that subject will be passed to the Administration for consideration. The publication of the final LRC report marks the completion of the reference, but the lawyers in the Secretariat will continue to play a part in the implementation of the LRC's recommendations. This may include promoting the recommendations by organising seminars and briefings, assisting in the preparation of legislative drafting instructions and the process of drafting any necessary legislations, providing further research materials and information to the Government bureaux which have policy responsibility for the subject, and attending to other matters arising from the implementation. The LRC also plays a monitoring role in the implementation of the LRC reports. Updates on progress of implementation are considered by members of the LRC regularly. The Chairman of the LRC also maintains regular contacts with the Administration, including the bureaux and departments having the policy carriage of the recommendations for reform. Starting from 2013, the Secretary for Justice is invited to report on an annual basis to the AJLS Panel of the LegCo on progress of implementation. Such first report was made to the AJLS Panel on 25 June 2013. Links with other law reform agencies An important element of almost every law reform project is an examination of relevant experience in other jurisdictions. The LRC Secretariat has arrangements with some 50 law reform agencies for the reciprocal exchange of reports and papers, and receives around 60 new reports and consultation papers each year. This materials are indexed on a comprehensive database, which provides an invaluable research tool. The LRC Secretariat's library now holds over 4,000 publications from law reform agencies in other jurisdictions. Lawyers in the LRC Secretariat also receive considerable assistance through correspondence and contact with their counterparts in other jurisdictions. In addition, much useful input is obtained from their attendance at local and overseas conferences which are relevant to their particular projects. In this globalized age, such link with overseas jurisdictions is essential to enable the LRC to keep abreast of what is happening in respect of law reform in the rest of the world. Internet services and the LRC website The use of the internet for research and communication plays a vital role in every project the LRC undertakes. All new reports and consultation papers are made available on the LRC’s website at the same time as they are published in hard copy. In addition, as part of a project to increase the accessibility of the LRC’s publications, a number of earlier reports which were published only in hard copy have been re-formatted and uploaded to the website. The English version of all of the LRC’s 61 reports are now available 9 online, and 56 of these are also available online in Chinese, including some early papers which were only published in English and have now been translated into Chinese. The LRC’s website also incorporates a portal to legal web-sites on the Internet, called “LAW LINKS”, developed by the LRC Secretariat. LAW LINKS includes more than 1,000 links to law related sites all over the world, including links to other law reform agencies, parliamentary sites, case report sites, law journal sites, sites on specific legal topics and a host of other sites which are likely to be of help to those carrying out legal research. LAWLINKS is available, free, to the public on the LRC’s website (http://www.hkreform.gov.hk). In addition, the LRC's reports and papers (in both English and Chinese languages) are also accessible in the website of the Hong Kong Legal Information Institute (http://www.hklii.hk/eng). Highlights of 2011 and 2012 Membership Five new members were appointed to the LRC during the period from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2012. Mrs Eleanor Ling, SBS, JP, joined the LRC on 1 June 2011, replacing Professor Felice Lieh-Mak, JP. Ms Angela Lee, BBS, JP, joined on 1 January 2012, replacing the Hon Anna Wu, SBS, JP, who retired from the LRC on 31 December 2011 after serving two threeyear terms. Mr Anderson Chow, SC, joined on 1 February 2012, replacing Mr Paul Shieh, SC, after serving the second three-year term. The Hon Mr Justice Robert Tang Ching, SBS, Permanent Judge of the Court of Final Appeal, was appointed on 1 October 2012, replacing the Hon Mr Justice Patrick Chan, Permanent Judge of the Court of Final Appeal, after serving the second three-year term. Mr Eugene Fung, SC, joined on 1 January 2013, replacing Mr Godfrey Lam, SC, on completion of his three-year term and his appointment as a judge of the Court of the First Instance of the High Court. During the same period, Mrs Pamela Chan, BBS, JP; Mr John Budge, SBS, JP; Mr Peter Rhodes; and Professor Michael Wilkinson were all re-appointed for a second three-year terms as members of the LRC. Consultation papers Three consultation papers were published during 2011 and 2012: Charities (June 2011); Rape and Other Non-consensual Sexual Offences (September 2012); and 10 Adverse Possession (December 2012). Reports The LRC completed work on three projects, with the publication of the following reports: Enduring Powers of Attorney: Personal Care (July 2011); Double Jeopardy (February 2012); and Class Actions (May 2012). Implementation The recommendations put forward in LRC reports are the result of detailed studies by the LRC and, in most cases, also by the relevant specialist subcommittees. It is in the interests of both the Administration and the LRC, and of the community, that the results of the LRC's work are given full and fair consideration within a reasonable timeframe. The longer the delay, the greater the risk that the LRC may have to conduct a fresh review and consultations. In the meantime, the original shortcomings in the law remain unresolved. However, it must also be borne in mind that the complexity and scope of the subject-matter of LRC reports vary greatly and some reports are likely to require longer than others for bureaux to consider. a) The Administrative Guidelines 2011 In some other jurisdictions, statutory or administrative guidelines for the consideration of law reform agency reports have been adopted. The advantage of such guidelines is that they encourage early consideration of law reform proposals and decisions on implementation while the law reform agency's original research and consultation remain valid, so avoiding subsequent effort to update the research and re-run the consultation. At the same time, it is important that any such scheme allows the Government sufficient time for proper consideration of law reform proposals, especially when they raise complex and controversial issues or policy implications. To address the concerns which have been expressed at delays in considering and implementing the LRC's proposals, the Director of Administration issued, in October 2011, a set of guidelines to bureaux and departments having policy responsibility over the subject matter of a LRC report. Details of the Administrative Guidelines 2011 are as follows: when a consultation paper is issued by the LRC, the Administration should at that stage decide which bureau or bureaux will take primary responsibility for consideration and implementation of the final report and 11 should so notify the LRC; the relevant bureau or department should provide the Secretary to the LRC with the contact details of the bureau's or department’s officer with responsibility for the LRC report within 14 days of receipt of the letter from the Secretary for Justice forwarding a LRC report to the responsible Policy Secretary and requesting consideration of the report; the relevant bureau and department having policy responsibility in respect of any LRC report should give full consideration to its recommendations and provide a detailed public response (setting out which recommendations they accept, reject or intend to implement in modified form) to the Secretary for Justice (as Chairman of the LRC) as soon as practicable. In any event, they should provide at least an interim response within six months of publication of the report which sets out a clear timetable for completion of the detailed response and the steps taken so far; and the relevant bureau or department having policy responsibility in respect of a LRC report should provide a detailed public response to the Secretary for Justice within 12 months of its publication, unless otherwise agreed by him as Chairman of the LRC. b) The LegCo Monitoring Mechanism 2012 The AJLS Panel of the LegCo has also expressed concern over the delay in the implementation of LRC recommendations. The AJLS Panel acknowledged that the recommendations put forward in a LRC report are the result of detailed study by LRC members, including both academic and practising lawyers and prominent members of the community who have rich experience and expertise in their respective professional or other fields, with input from its various sub-committees comprising members drawn from a wide pool of talents in the community and within the Administration. The AJLS Panel is of the view that Secretary for Justice, in addition to the role as the Chairman of the LRC, has the responsibility to keep Hong Kong's system of laws up-todate, and other Panels of the LegCo also have a role to play in facilitating the law reform work. To ensure that the LRC's recommendations are given consideration within a reasonable timeframe and would be implemented without undue delay, the AJLS Panel proposed in February 2012, as subsequently endorsed by the LegCo House Committee, that the Secretary for Justice should submit for discussion an annual report on progress of implementation of the LRC recommendations. Details of the LegCo Monitoring Mechanism are as follows: the Secretary for Justice submits to the AJLS Panel of the LegCo for discussion an annual report addressing the progress in respect of the LRC reports which have not yet been implemented, say, after the Policy 12 Address in each year; the AJLS Panel copies the annual report to other relevant Panels of the LegCo to facilitate their follow-up with the bureaux and departments having policy responsibility over the respective LRC reports; and the relevant Panels of the LegCo include the Administration's responses to the respective LRC reports in their lists of outstanding items for discussion, and invite members of the AJLS Panel and other Members of the LegCo to join the future discussion. Current projects Adverse possession Adverse possession is the process by which a person can acquire title to someone else's land by continuously occupying it in a way inconsistent with the rights of its owner. If the person in adverse possession (the squatter) continues to occupy the land, and the owner does not exercise the owner’s right to recover it by the end of a period prescribed by law, the owner's remedy, as well as title to the land, will be extinguished and the squatter will then become the new owner. The main provisions on adverse possession can be found in the Limitation Ordinance (Cap 347). Except in the case of Government land for which the limitation period is 60 years, no action to recover landed property is allowed after 12 years from the date upon which the right of action accrued. Time starts to run when the owner has been dispossessed of the land and the squatter has taken possession of the land. The Adverse Possession Sub-committee was established in September 2006 under the chairmanship of Mr Edward Chan, SC, to consider possible reforms to the law of adverse possession. On 10 December 2012, the Sub-committee released a consultation paper making preliminary proposals for the reform of the law on adverse possession. The preliminary recommendations of the Sub-committee are made against a background of a deeds registration system as opposed to a title registration system of conveyancing in Hong Kong. The consultation paper discussed that despite the enactment of the Land Titles Ordinance (Cap 585) in 2004, the Ordinance is not yet implemented. The existing deeds registration system gives no guarantee of title. Even if a person is registered as the owner of a property, there may still be uncertainties or defects in the person’s title to the property. Hence, title to land is relative and depends ultimately upon possession. The Sub-committee has considered the cases decided in Hong Kong and 13 overseas and made recommendations on various aspects of the law. In view of the broader and on-going reviews of the Land Titles Ordinance, the Subcommittee has also made recommendations applicable to Hong Kong when a registered title regime is put in place. The Sub-committee will submit a final report to the LRC after considering the responses received during the consultation period which ended in March 2013. The Sub-committee's secretary is Ms Cathy Wan, Senior Government Counsel. Review of sexual offences The range of sexual offences under the criminal law includes rape, buggery, gross indecency, indecent assault, abduction, incest and other unlawful sexual acts. The existing law has been criticized because some of these offences are gender-specific, while others are based on sexual orientation. There are also concerns that the existing sexual offences may not adequately reflect the range of non-consensual conduct which should be subject to criminal sanction. The maximum sentences that are applicable to the various offences may also need to be reviewed. A Sub-committee, chaired by Mr Peter Duncan, SC, began work on this subject in August 2006. The terms of reference of the Sub-committee were revised in October 2006 to include consideration of the establishment of a register of sex offenders. The Sub-committee published a consultation paper in July 2008 and the LRC’s report, recommending an interim scheme for sexual offences records checks for child-related work, was published in February 2010. In December 2010, the Sub-committee issued a report recommending the abolition of the common law presumption that a boy under 14 years of age is incapable of sexual intercourse. In September 2012, the Sub-committee released a consultation paper proposing a newly defined offence of rape and the creation of a range of other non-consensual sexual offences. The Sub-committee’s remaining tasks include a review of sexual offences against children, the mentally incapacitated, those involving abuse of a position of trust as well as other miscellaneous offences and also sentencing. The Sub-committee's secretary is Mr Thomas Leung, Senior Government Counsel. Causing or allowing the death of a child Where a child dies as a result of abuse at home, it may not be possible for the law enforcement agencies to prove beyond reasonable doubt which of the adults caring for the child inflicted the fatal injuries. As a result, the party who killed the child, and a party who stood by and allowed it to happen, may 14 literally "get away with murder" in some cases. In other jurisdictions, new criminal offences and rules of procedure have been introduced to counter this problem. In England, for example, section 5 of the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004 allows the court to convict and imprison for up to 14 years those who have caused the death of a child or should have known that the child was at significant risk of serious harm and failed to take reasonable steps to prevent that harm. South Australia enacted legislation along broadly similar lines in 2005 and a more recent reform model came into operation in New Zealand in 2012. To consider whether reform may be required to the law in Hong Kong, the subject of causing or allowing the death of a child was referred to the LRC in September 2006. A Sub-committee, under the chairmanship of Mr Alexander King, SC, began work on this subject in December 2006. The Sub-committee's secretary is Ms Michelle Ainsworth, Deputy Principal Government Counsel. Charities There is currently no single piece of legislation which governs charities in Hong Kong, nor is there any system of oversight or regulation to ensure that donations are properly applied to the purposes for which they are solicited. In addition, there is no statutory definition of what constitutes a charity or a charitable purpose and there is no statutory requirement in Hong Kong for charitable organisations to submit annual reports or accounts reporting their finances. Legislation governing charities exists in a number of other jurisdictions, and in some cases there are statutory organisations supervising charities and ensuring that they are administered properly. In June 2007, the LRC agreed to review the law and regulatory framework relating to charities in Hong Kong. A Sub-committee chaired by the Hon Bernard C Chan, GBS, JP, was formed and held its first meeting in November 2007. In June 2011, the Sub-committee issued a consultation paper setting out its provisional recommendations. Some of the provisional recommendations have turned out to be controversial, and much responses and comments have been received during consultation. A final report will soon be issued by the LRC upon completion of the analyses of the responses received from various stakeholders. The Sub-committee's secretary is Ms Kitty Fung, Senior Government Counsel. 15 Excepted offences under Schedule 3 to the Criminal Procedure Ordinance (Cap 221) The subject matter arose from a letter of the Law Society addressed to the Secretary for Justice dated 22 March 2010 suggesting reforms in this area, relying on the Court of Appeal's judgment in AG v Ng Chak Hung, Application for Review 1994, No 1. At issue is whether there is a need to keep the provisions in the Criminal Procedure Ordinance (Cap 221) which prohibit a suspended sentence from being imposed in respect of any of the "excepted offences" listed at Schedule 3 to Cap 221, and if not, whether those provisions should be amended or repealed. In October 2012, the Centre of Comparative and Public Law (University of Hong Kong) prepared a report on this topic. The LRC subsequently decided that a fast-track approach should be adopted to review the law relating to excluding the availability of suspended sentences from excepted offences as listed in Schedule 3 to Cap 221, and to make such recommendations for reform as appropriate, in light of the feedback of a public consultation paper to be published in summer 2013. The subject officer of this project is Mr Byron Leung, Senior Government Counsel. Archives law The Director of Administration, head of the Administration Wing of the Chief Secretary for Administration's Office, and the Government Records Service under the Administration Wing develop, in the absence of legislation, policies, administrative directives and guidelines to regulate the management of Government records. In May 2013, a Sub-committee chaired by Hon Andrew Liao, SC, was formed to review the present situation, as well as to conduct comparative studies of the relevant laws in other jurisdictions, with a view to making appropriate recommendations on possible options for reform if need be. The Sub-committee’s secretary is Mr Byron Leung, Senior Government Counsel. 16 Access to information Currently, there is no legislation governing access to information held by the Government. There, however, exists a Code on Access to Information which, inter alia, defines the scope of information that will be provided, sets out how the information will be made available and lays down the relevant procedures. There have been calls for putting in place a statutory scheme dealing with the right to access information held by the Government. In May 2013, a Sub-committee chaired by Mr Russell Coleman, SC, was formed to conduct detailed reviews of the local situation and comprehensive comparative studies of the relevant laws in overseas jurisdictions, with a view to making appropriate recommendations on possible options for reform where appropriate. The Sub-committee’s secretary is Mr Stephen Kai-yi Wong, Principal Government Counsel. Third Party Funding for Arbitration Third party funding ("TPF") refers to a contractual agreement between a third party (the funder) and a claimant seeking to pursue a cause of action. TPF arrangements are usually motivated by a lack of financial resources but may also be used to mitigate costs and manage the risk of litigation or arbitration. The contract commonly provides that the funder will pay for the costs of the action in return for a percentage of the award should the action succeed. In the context of litigation, TPF may involve unlawful conduct and is a controversial topic. However, the considerations in respect of TPF in the context of arbitration, especially international commercial arbitration, are different. Besides, reform in this area, if appropriate, may be conducive to implementing the policy of promoting Hong Kong as an international arbitration centre in the Asia Pacific region. In June 2013, a Sub-committee, chaired by Ms Kim Rooney, was set up to review the current position relating to TPF for arbitration for the purposes of considering whether reform is needed, and if so, to make such recommendations for reform as appropriate. The Sub-committee's secretary is Ms Kitty Fung, Senior Government Counsel. 17 How to contact the LRC You can obtain further information on the LRC by writing to Mr Stephen Kai-yi Wong, Secretary to the Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong, at 20/F Harcourt House, 39 Gloucester Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong (fax 2865 2902 and tel 2528 0472). Alternatively, you can find the LRC’s Home Page at http://www.hkreform.gov.hk or email us at hklrc@hkreform.gov.hk - End 18 - Annex Members of the LRC (as at 30 June 2013) Hon Rimsky Yuen, SC, JP, Secretary for Justice (Chairman) Hon Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma, GBM, Chief Justice of the Court of Final Appeal Hon Mr Justice Robert Tang Ching, SBS, Permanent Judge of the Court of Final Appeal Mr Paul Wan How-leung, JP, Law Draftsman Mrs Pamela Chan, BBS, JP, former Chief Executive of the Consumer Council Mr John Budge, SBS, JP, Partner, Wilkinson & Grist, Solicitors Mr Peter Rhodes, Faculty of Law, Chinese University of Hong Kong Professor Michael Wilkinson, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong Mrs Eleanor Ling, SBS, OBE, JP, Adviser to the Board, Jardine Matheson Limited Ms Angela Lee, BBS, JP, Consultant, Baker & Mackenzie, Solicitors Mr Anderson Chow, SC, Barrister Mr Eugene Fung, SC, Barrister Members of the LRC Secretariat Mr Stephen Kai-yi Wong, Secretary to LRC (Principal Government Counsel) Ms Michelle Ainsworth, Deputy Secretary to LRC (Deputy Principal Government Counsel) Ms Kitty Fung, Senior Government Counsel Mr Byron Leung, Senior Government Counsel Mr Thomas Leung, Senior Government Counsel Ms Cathy Wan, Senior Government Counsel 19 Members of LRC sub-committees Adverse possession Mr Edward Chan, SC, JP, Barrister (Chairman) Dr Patrick Hase, Historian Professor Leung Shou-chun, Surveyor Mr Louis Loong, Secretary General, Real Estate Developers Association Ms Polly Yip, Assistant Director / Legal, Lands Department Professor Michael Wilkinson, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong Mr David P H Wong, Partner, Wong, Hui & Co., Solicitors Mr Michael Yin, Barrister Review of sexual offences Mr Peter Duncan, SC, Barrister (Chairman) Hon Mrs Justice Barnes, Judge of the Court of First Instance of the High Court Mr Eric T M Cheung, Assistant Professor, Department of Professional Legal Education, University of Hong Kong Mr Fung Man-chung, Assistant Director (Family & Child Welfare), Social Welfare Department Professor Karen A Joe Laidler, Director, Centre for Criminology and Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Hong Kong Mrs Millie Ng, Principal Assistant Secretary for Security, Security Bureau Ms Pang Mo-yin, Senior Superintendent of Police, Crime Wing, Hong Kong Police Force Mr Andrew Powner, Partner, Haldanes, Solicitors Ms Lisa Remedios, Barrister Mr Philip Ross, Barrister 20 Dr Alain Sham, Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions, Department of Justice Causing or allowing the death of a child Mr Alexander King, SC, Barrister (Chairman) Dr Philip Beh, Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, University of Hong Kong Ms Diane Crebbin, Department of Justice Mr Stephen Hung, Partner, Pang, Wan & Choi, Solicitors Mrs Chang Lam Sook-yee, Chief Social Work Officer (Domestic Violence)(Acting), Social Welfare Department Ms Jacqueline Leong, SC, Barrister Ms Pang Mo-yin, Senior Superintendent of Police, Crime Wing, Hong Kong Police Force Ms Lisa Remedios, Barrister Mr John Saunders, SBS, former Judge of the Court of First Instance of the High Court Ms Amanda Whitfort, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong Barrister, former Senior Public Prosecutor, Charities Hon Bernard Chan, GBS, JP, ExCo member, Chairman of the Hong Kong Council of Social Service (Chairman) Mr John Budge, SBS, JP, Partner, Wilkinson & Grist, Solicitors Mrs Pamela Chan, BBS, JP, former Chief Executive of the Consumer Council Ms Christine Fang, BBS, JP, Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Council of Social Service Mr Adam Koo, CEO of WWF Hong Kong Mr Herbert Tsoi, BBS, JP, Partner, Herbert Tsoi & Partners 21 Ms Florence Wai, CEO (Lotteries Fund), Social Welfare Department Mr Leonard Wong, Chief Assessor (Special Duties), Inland Revenue Department Archives law Hon Andrew Liao, GBS, SC, JP, ExCo member, Barrister (Chairman) Mr Michael Chan, Consultant, Wilkinson & Grist, Solicitors Ms Kitty Choi, JP, Director of Administration, Administration Wing, Chief Secretary for Administration’s Office Ms Stacy Gould, University Archivist, University of Hong Kong Mr Richard Khaw, Barrister Mr Gordon Leung, JP, Deputy Secretary, Constitutional & Mainland Affairs, Constitutional & Mainland Affairs Bureau Access to information Mr Russell Coleman, SC, Barrister (Chairman) Mr Eric Chan, Associate Publisher / Chief Editor, Hong Kong Economic Times Dr Andy Chiu, Head, Department of Law and Business, Hong Kong Shue Yan University Ms Kitty Choi, JP, Director of Administration, Administration Wing, Chief Secretary for Administration’s Office Mr Brian Gilchrist, Partner, Clifford Chance, Solicitors Mr Gordon Leung, JP, Deputy Secretary, Constitutional & Mainland Affairs, Constitutional & Mainland Affairs Bureau Mr Jose-Antonio Maurellet, Barrister 22 Third Party Funding for Arbitration Ms Kim M. Rooney, Barrister (Chairman) Ms Teresa Y.W. Cheng, SC, Barrister Mr Robert Y.H. Pang, SC, Barrister Mr Justin D'Agostino, Managing Partner - China, Herbert Smith Freehills, Solicitors Mr Victor Dawes, Barrister 23