Word | Complete Guide

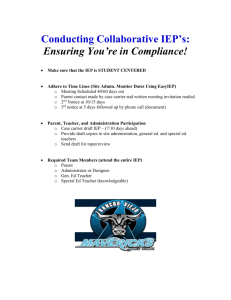

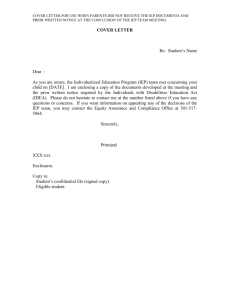

advertisement