Mughal miniatures share these basic characteristics,

advertisement

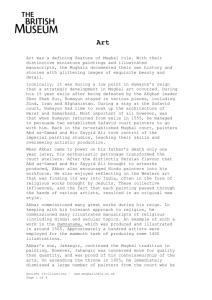

Mughal miniatures share these basic characteristics, but they also incorporate interesting innovations. Many of these deviations results from the fact that European prints and art objects had been available in India since the establishment of new trading colonies along the western coast in the sixteenth century. Mughal artists thus added to traditional Persian and Islamic forms by including European techniques such as shading and atmospheric perspective. It is interesting to note that European artists were likewise interested in Mughal painting—the Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn collected and copied such works, as did later artists such as Sir Joshua Reynolds and William Morris. These images continued to interest westerners in the Victorian era, during the period of Art Nouveau, and even today. [For a demonstration of Persian miniature painting, see http://vimeo. com/35276945.] The Depiction of the Ruler in Mughal Miniature Painting While Humayun was largely responsible for the importation of Persian painters to India, it was under Akbar that Mughal miniature painting first truly flourished. Akbar maintained an imperial studio where more than a hundred artists illustrated classical Persian literary texts, as well as the Mahabharata, the great Hindu epic that the emperor had translated into Persian from its original Sanskrit. Akbar also sponsored various books describing his own good deeds and those of his ancestors. Such books were expansive—some were five hundred pages long, with more than a hundred miniature paintings illustrating the text. It is here that we see the first concentrated focus on painted imagery dedicated to the Mughal rulers, and where the standards for such images are firmly established. The “Patna’s Drawings” Album, created under the rule of Akbar’s celebrated decendant Shahjahan, is a wonderful later example of this type of presentation. The album is a continuation and fortification of the Mughal miniature painting tradition celebrating kingship. The “Patna’s Drawings” Album Albums such as the one of which our selected work, the image of Shahjahan, is a part were generally made by royal commission.37 Called muraqqa, they were intended to serve as private luxury works, to be leafed through and enjoyed at leisure by the emperor and his friends and family. Such objects would have originally been preserved in the imperial collection and passed along through generations. Considering their purpose and provenance, it is quite surprising that only one mid-seventeenth-century imperial album of paintings and calligraphies has remained intact and in its original binding. The British Library holds this album, which was commissioned by Prince Dara-Shikoh in 1633 and presented to his wife Nadira Banu Begum in 1642. All of the other royal albums eventually left the imperial library, either in 1739 74 Portrait of the emperor Shahjahan, enthroned, from the “Patna’s Drawings” Album. when Nadir Shah of Persia sacked New Delhi, or in the early nineteenth century, as antiquities dealers purchased what was left from the increasingly weakened Mughal court. Over time, many of the albums were broken up, augmented with additional materials, and rebound. Certainly many were lost as well. In general, such albums were of a consistent format and style. The book was introduced with imperial seals and calligraphy pages, noting and hailing the emperor for whom it was commissioned. The albums included portrait miniatures of the ruler, his ancestors, and other members of the imperial family, as well as various dignitaries and holy men. These portraits were arranged according to the hierarchy of the court and were often supported by additional calligraphy elements. Many albums also included natural history studies, particularly botanical imagery. Such foliate decoration was also often seen in the borders of the various folio pages. According to the Bodleian Library which holds it, the “Patna’s Drawings” Album includes a total of forty-one paintings, largely from the period of Shahjahan’s reign USAD Art Resource Guide • 2015-2016