Egypt

advertisement

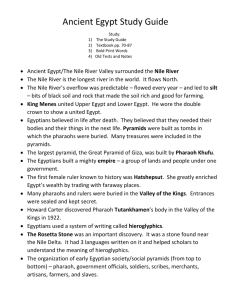

Ancient: Egypt Egypt North Africa is dominated by the Sahara Desert, a hot, dry wasteland as large as the United States. Only the Nile River, flowing north through the desert, interrupts the arid expanse. Although some north Africans settled along the mild coastline, most North Africans, however, settled near the Nile River, where they clustered in farming villages along its fertile floodplains. These villages eventually formed the foundations of large, complex, dynamic societies later called Egypt. In the fourth millennium BCE, as the Nile Valley population grew, towns and villages along the river united into small kingdoms. These early states organized irrigation bringing river water to farm fields. By 3100 B.C.E., through various conflicts and conquests, the northern realms combined into a Kingdom of Egypt, which became one of the ancient world's most powerful and prosperous realms. In some ways, developments in Egypt paralleled those in Mesopotamia. As in Mesopotamia, smaller states combined by conquest into larger domains, with powerful rulers, polytheistic religions, writing systems, and extensive commerce. In other ways, however, Egypt differed markedly from Mesopotamia. Separated by seas and deserts from potential foes, and blessed by a river whose annual, soil-enriching floods helped farmers produce ample crops year after year – ancient Egypt was bountiful, powerful, extensive, and predictable, much like the Nile River. More stable and predictable, Egyptian society gradually developed belief in life after death, prompting efforts to preserve and house the remains of rulers and other prominent people. Central to Egypt's worldview was the concept that the universe's elemental order encompassed truth, justice, harmony, and balance. The rulers, called pharaohs, were powerful, godlike figures whose main duty was to maintain this order. The sun god and chief divinity ruled the heavens much as pharaohs ruled the earth. Religion and governance in Egypt were one and the same. Other popular gods became symbols of fertility, devotion, and the victory of life over death, inspiring an outlook far more hopeful than that of early Mesopotamian religion. Sustained by such myths and the cycles of the Nile, whose annual soil-renewing floods were more regular and predictable than floods in Mesopotamia, Egyptians concluded that life was renewable and cyclical. They came to believe that death was not the end of life, that honorable living would merit eternal life. Religion thus reinforced morality, as the prospect of attaining life after death promoted honorable behavior. The prospect of life after death also promoted mummification, an elaborate process for preserving the bodies of prominent people after death. Like the early Mesopotamians, ancient Egyptians made momentous contributions to culture, knowledge, and communication. They produced impressive artworks, decorating temples and tombs with splendid paintings and sculptures. They charted constellations, created a calendar, and practiced medicine based on natural remedies. They even invented an accounting system and developed mathematics to advance their architectural and engineering skills. Egyptians also devised a form of writing now called hieroglyphs. Like Sumerian cuneiform, it began in the fourth millennium BCE with pictographs, to which were added symbols for ideas and sounds. Like the Sumerians, Egyptians trained scribes to master and use their writing system. Unlike the Sumerians, however, Egyptian scribes wrote with ink-dipped reeds on papyrus, a paperlike material made from plants that grew along the Nile, and rolled it into scrolls for easy storage or transport. Far less cumbersome than Sumerian clay tablets, the scrolls helped Egyptians readily record their legends, laws, rituals, and exploits. Deciphered records reveal that Egypt had a high degree of political and social stratification. They also show that life focused mainly on family, farming, and the Nile. Egyptian society was structured by status and wealth. Upper classes of priests and state officials lived in luxury; middle classes of merchants, scribes, and artisans enjoyed some prosperity; and lower classes of peasants and laborers worked hard to barely survive. Most Egyptians were peasants: humble farmers and herders raising wheat, barley, cotton, sheep, and cattle. Marriage and family were central to Egypt's society. Some men practiced polygyny, meaning they had more than one wife, but marriages were mostly monogamous. As in West Asia, husbands provided the homestead while wives brought a dowry and furnishings into the marriage. Gender roles were well defined but not rigid. In lower-class households men mostly worked the fields, but they might also be hunters, miners, craftsmen, or construction workers. Women mainly did household tasks, such as cooking and making clothes. But women in Egypt seem to have had higher status than those in West Asia. Egyptian women could own and inherit property, seek and obtain a divorce, and pursue trades such as entertaining, nursing, and brewing beer. Furthermore, in contrast to West Asian households, Egyptian families often were matrilineal, with property descending through the female line, and wives in Egypt were recognized as dominant in the home. Egyptian priestesses played key roles in religion, and a few women even served as rulers. But governance and warfare were, as elsewhere, mainly the work of men. The rhythm of work in Egypt followed the ebb and flow of the Nile, which typically flooded between July and September. In October, once the waters receded, the growing season began. Aided by oxen and other farm animals, peasants plowed fields and planted crops, then tended them, bringing buckets of water from irrigation canals. The harvest usually started in February, with women and children helping the men gather crops and thresh grain. The main crops were wheat and barley, but Egyptians also grew dates, grapes, and other fruits and vegetables. In years when food was abundant, the government stored some of the grain for use in times of scarcity. Large projects needing many workers, including construction and repair of palaces, temples, and irrigation systems, normally started once the harvest was over. Egypt's kings ruled a mostly peaceful and stable society. Internally they created a centralized state with an effective bureaucracy and tax collection system. Externally they established connections and traded with other societies, while largely avoiding warfare. Their most enduring achievements were the pyramids, monumental structures with triangular sides sloping upward toward a point. Around 1200 BCE, faced with new commercial and military challenges, Egypt's dominance waned, and power in northeastern Africa shifted to the south to the Kush of modern day Sudan. 2