114-2008-P (3rd Party) (5 December 2008)

advertisement

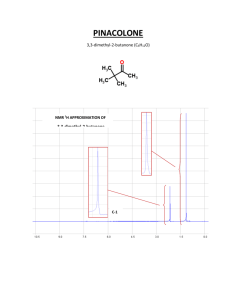

CITATION: Stephen McNamee v Development Consent Authority and June D’Rozario LPMT 114-2008-P (20828851) 3 rd Party Appeal PARTIES: STEPHEN MCNAMEE v DEVELOPMENT CONSENT AUTHORITY AND JUNE D’ROZARIO TITLE OF COURT LANDS PLANNING AND MINING TRIBUNAL JURISDICTION: LANDS PLANNING AND MINING TRIBUNAL ACT FILE NO(s): LPMT-114-2008-P / 3 rd Party Appeal DELIVERED ON: 5 December 2008 DELIVERED AT: DARWIN HEARING DATE(s): 3 November 2008 DECISION OF: Dr John LOWNDES, CHAIRPERSON CATCHWORDS: PLANNING APPEAL – THIRD PARTY APPEAL – PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING LOCUS STANDI – MEANING OF WORD “ADJACENT” IN PLANNING APPEAL PROVISION – MATTER OF STATUTORY INTERPRETATION Planning Act ss 11(3), 53(b), 117, 118 Interpretation Act s62A Lands Planning and Mining Tribunal Rules Rule 9(1) Planning Regulations Regulation 14 Geneff and Ors and Shire of Perth (1966) LGRA 145 considered Federal Commissioner of Taxation v BHP Minerals Ltd (1983) 51 ALR 166 considered Hornsby Shire Council v Malcolm 91966) 60 LGRA 429 considered 1 REPRESENTATION: Counsel: Appellant: Respondent: Susan Porter Caroline Bicheno Solicitors: Appellant: Respondent: William Forster Chambers Solicitor for the Northern Territory Judgment category classification: Judgment ID number: Number of paragraphs: B LPMT 114 55 2 IN THE LANDS PLANNING AND MINING TRIBUNAL AT DARWIN IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA No. LPMT 114-2008-P (20828851) 3 rd Party Appeal BETWEEN: STEPHEN McNAMEE Appellant AND: DEVELOPMENT CONSENT AUTHORITY Respondent AND: JUNE D’ROZARIO 2 nd Respondent DECISION (Delivered 5 December 2008) Dr John LOWNDES, CHAIRPERSON THE PRELIMINARY ISSUE IN THESE PROCEEDINGS On 20 October 2008 the appellant lodged a Notice of Appeal pursuant to s 118 of the Planning Act, the appeal being in the nature of a third party appeal (s 117 of the Act). The appeal relates to a Notice of Consent to a proposed development on Lots 4858 and 5705 Buffalo Court, Town of Darwin. By way of that Notice of Consent the Development Consent Authority determined in accordance with s 53(b) of the Planning Act to alter the development proposal and grant consent to use and develop the subject land for 3 the purpose of 220 hotel suites, 28 serviced apartments, 21 x 1, 14 x 2 and 21 x 3 bedroom multiple dwellings, shop (liquor store), restaurant and hotel/tavern in a 14 storey building including 3 levels of car parking, subject to the conditions specified on Devel opment Permit DP08/0598. A preliminary issue arises out of the lodgement of the appeal. Does the appellant have a right of appeal according to the third party appeal provisions set out in s 117 of the Planning Act? THE PROCEDURAL ASPECTS There are no specific provisions under the Planning Act to facilitate the determination of a preliminary issue of the present type. The scheme of the Act is that the Tribunal only becomes seized of a matter after it has been referred to mediation and mediation has been unsuccessful. It makes good sense to deal with the threshold issue in the present proceeding as quickly as possible because it goes to the heart of the matter. If the appellant has no right of appeal it makes no sense for this matter to be referred to mediation (which cannot dispose of the issue) and subsequently to the Tribunal for a determination on the merits. If the matter were to run that course the proceedings would be unduly protracted and incur unnecessary expense. With those considerations in mind, the Tribunal relied upon the provisions of s 11(3) of the Lands Planning and Mining Tribunal Act which provides: Subject to this Part and any other Act, the practice and procedure of the Tribunal is to be – (a) as prescribed by the rules; or (b) if no practice or procedure is prescribed by the rules – as determined by the Tribunal. Rule 9(1) of the Lands and Mining Tribunal Rules provides: 4 Unless the Tribunal directs otherwise, an application in a proceeding is to – (a) be in accordance with Form 4; (b) include a brief statement of the orders or directions sought; (c) be supported by an affidavit unless the application relates to a procedural matter; and (d) be filed in sufficient numbers to enable service of a copy, sealed by the Registrar, on each party. The preliminary issue in the present proceeding was brought before the Tribunal by the appellant filing an application in accordance with Rule 9(1). All parties to the appeal agreed with the matter proceeding in that manner. Regardless of Rule 9(1), the Tribunal has power to deal with the preliminary issue by reason of s 11(3)(b). THE THIRD PARTY APPEAL PROVISIONS Section 117 of the Planning Act is set out in its entirety: 1. Subject to the Regulations, a person or local authority who made a submission in accordance with section 49 in relation to a development application may appeal to the Appeals Tribunal against a determination under section 53(a) or (b) – (a) to consent to the development, as proposed or as altered; or (b) to impose conditions on the proposed development or pr oposed altered development, including a condition referred to in section 70(3). 2. The appeal must be made within 14 days after the person or local authority is served with the notice of determination in respect of the development application. 3. A person or local authority must not appeal under this section for reasons for commercial competition. 4. The Regulations may specify other circumstances under which there is no right of appeal under this section, including by reference to the type of development in conjunction with – (a) the zone of the land on which the development is to take place; (b) the zone of land adjacent to the land on which the development is to take place; or 5 (c) the zone of land referred to in both paragraph (a) and (b) Example for section 117 – The Regulations may specify there is no right of appeal in respect of development of land zoned for industrial use or development unless the land is adjacent to land zoned for residential use or development. The relevant regulation is Regulation 14 of the Planning Regulations, which provides: 1. This regulation specifies circumstances under which there is no right of appeal under section 117 of the Act against a determination of the consent authority relating to development of land to which the NT Planning Sch eme applies. 2. There is no right of appeal if the determination relates to the subdivision or consolidation of land. 3. There is no right of appeal if the determination relates to any of the following proposed developments on land to which a planning control provision applies: (a) a single dwelling or multiple dwelling not exceeding 2 storeys above ground level; (b) setbacks for a single dwelling; (c) any other type of development on land in a residential zone if it complies with all the planning control provisions relating to the development; (d) any other type of development on land that is not in a residential zone, or for which no zone is specified, unless the land: (i) is adjacent to land in a residential zone; or (ii) is directly opposite land in a residential zone and is on the other side of a road with a reserve of 18m or less in width. DOES THE APPELLANT HAVE A RIGHT OF APPEAL The preconditions of a right of appeal Section 117 of the Planning Act read in conjunction with Regulation 14 of the Planning Regulations prescribes a number of preconditions that need to be satisfied in order to create a right of appeal. 6 The appellant satisfies the requirements of s 117(1) of the Act. He made a submission in accordance with s 49 in relation to a development application. The appeal has been lodged within the time prescribed by s 117(2) of the Act and has not, in contravention of s 117(3), been brought for reasons of commercial competition. The appellant is not denied a right of appeal by reason of sub regulations (2) and (3)(a), 3(b) and 3(c). The development application which was approved by the Development Consent Authority relates to land which is not in a residential zone, that is the land is zoned “CB” (Central Business). In accordance with Regulation 14(3)(d) of the Planning Regulations the appellant has a right of appeal only if it be shown that the approved development is adjacent to land in a residential zone or is directly opposite land in a residential zone and is on the other side of a road with a reserve of 18m or less in width. The appellant contends that the approved development is adjacent to land in zone MD (a residential zone). The geographical relationship between the land on which the development has been approved (being within zone CB) and the nearest land i n zone MD is depicted in the colour coded diagram appended to these reasons for decision. Whether or not the precondition in Regulation 14(3)(d)(i) has been satisfied depends entirely upon the meaning to be attributed to the word “adjacent” as appears in that provision; and that is a matter of statutory interpretation. 7 Statutory Construction of Regulation 14(3)(d)(i) and (ii) The word “adjacent” is “one of those vague words which the draftsman of statutes and by laws is sometimes compelled to adopt”, it being well established law that “it is not a word to which a precise and uniform meaning is attached by ordinary usage”. 1 The shifting meaning of the word “adjacent” The imprecise and shifting meaning of the word “adjacent” is demonstrated by the following dictionary meanings of that word. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines “adjacent” as meaning “lying near to; adjoining; bordering”. According to the Macquarie Dictionary, “adjacent” means “lying near, close, or contiguous; adjoining; neighbouring”. The Australian Legal Dictionary defines “adjacent” as “near or close; a degree of proximity determined as a question of fact and not confined to that which is immediately adjoining”. As held by the New Zealand Supreme Court, whether or not something can be said to be “adjacent” must depend upon the facts and upon the proper construction of the document in which the term appears: see Claney v Bland (1958) NZLR 763. It is useful to begin by examining the various meanings accorded to the word “adjacent” in different contexts. In Geneff and Others and Shire of Perth (1966) LGRA 145 at p149 Jackson J stated: The question is, in relation to any particular street, what is meant by the phrase “land adjacent to the street”. No doubt, “adjacent” has a wider meaning than “adjoining”, which is defined in s 6 to be contiguous; it would include a street nearby or close to: see the definition of “adjacent” in the Oxford Dictionary and 1 Gifford Town and Planning and Local Government Guide September 1959 at [284]. 8 the reference to the same word by Sir Arthur W ilson delivering the judgment in Wellington Corporation v Lower Hutt Corporation : [1904] AC773 at p 775. In English Clays Lovering Pochin & Co Pty Ltd v Plymouth Corporation [1974] 1 WLR 742 at p 746 the Court of Appeal said: “Adjacent” means close to or nearby or lying by: its significance o r application in point of distance depends on the circumstances in which the word is used. The meaning of the word “adjacent” was considered by Sheppard J in Sealey v O’Shea (1976) 33 LGRA 25 at p 229: The word “adjacent” is to be compared with the word “a djoining”. It means lying near to but not necessarily touching. It can, however, sometimes mean adjoining or bordering. In Wellington v Lower Hut the Privy Council said [1904] AC 773 at pp 775, 776): “adjacent” is not a word to which a precise and uniform meaning is attached by ordinary usage. It is not confined to places adjoining, and it includes places close to or near. W hat degree of proximity would justify the application of the word is entirely a matter of circumstance. In Cross v Manning Shire Council (1980) 49 LGRA 1 at 9 the Court had occasion to consider the meaning of the word “adjacent” in the following definition of land: “the aggregation of all adjoining or adjacent lands held in the same ownership”: No doubt “adjacent” means separated only by a road or river or some type of separation. The Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia considered the meaning of “adjacent” in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v BHP Minerals Ltd (1983) 51 ALR 166 at 173. The Court held: It is some help to consider the meaning of synonyms such as “neighbouring”, “adjoining” and “contiguous” “Neighbouring” is perhaps the broadest of these concepts and suggests that things are close to each other. “Adjoining” suggests a closer relationship than “neighbouring”, generally connoting places being connected or in contact. “Contiguous” suggests to us a greater degree of connection between elements, requiring that they touch or contact each other. Interestingly, Collins English Dictionary …defines “contiguous” as “physically a djacent”. “Adjacent” is a word that is capable of a broad connotation. It can suggest a relationship like that indicated by “neighbouring”; but it can also be used in a sense akin to “contiguous”. 9 The Court went on to state (at 174): An ordinary and natural meaning of the word “adjacent” is “near” or “close”… ”It does not necessarily import the notion of side -by-side placement.” In Commissioner of Highways v Tynan (1982) 53 LGRA 1 at 18 Well J, when considering the meaning of “adjoining” and “adjacent”, hel d that: “The words are not coterminous in meaning: that which adjoins is adjacent; but that which is adjacent may not adjoin. ” The context dependant nature of the word “adjacent” was considered by McCullough J in Corfe Transport Ltd v Gwynnedd County Coun cil (1983) 81 LGR (UK) 745 at 753: In the context in which I have to consider the word “adjacent” I do not believe that it was meant to refer to premises which were merely near, even very near, to a road which is made the subject of the traffic regulation order. [The]…section [is] concerned with premises whose access leads directly onto a restricted road (whether the premises themselves are on the road or merely reach from it as, for example, by a right of way over premises which are themselves on the road) and with premises which can only be reached from a restricted road. Buckley LJ in Cave v Horsell [1912] 3 KB 533 at 544 drew the following distinction between “adjoining”, “adjacent” and “contiguous”: There are three words, “adjoining”, “adjacent” and “co ntiguous” which lie not far apart in the meaning which they convey. But of no one of them can its meaning be stated with exactitude and without exception. As to “adjoining” the expression “next adjoining” or “immediately adjoining” is common and legitimate. The expression at once conveys that two things may adjoin which are not next to each other. “Adjacent” conveys that which lies “near to” rather than that which lies “next to”. “Contiguous” is perhaps of all three the least exact. Any one of the three may by its context be shown to convey “neighbouring” without the necessity of physical contact. The meaning of the word “adjacent” in the present statutory context As observed by Preston CJ in ACN 115 840 509 v Kiama MC (2006) 145 LGERA 147 at 157 “words are chameleons that take their colour from their context”. 10 Relevantly, it was pointed out in Hornsby Shire Council v Malcolm (1986) 60 LGRA 429 at 443 that the word “adjacent” takes its colour from the context in which it appears. Gifford and Gifford point out the need for a word or words to be read in light of a section as a whole: In some cases the reading of the word in the light of its context may give a wider meaning than it would have had if read on its own, and in other cases the meaning of the word when read in its context may be narrower than it would otherwise have been. 2 This approach requires the meaning of the word “adjacent” in regulation 14(3)(d)(i) to be considered in the context of the entire regulation: regard must also be had to regulation 14(3)(d)(ii), for it may shed light on the meaning of “adjacent” in the preceding regulation. Regulation 14(3)(d)(ii) requires a degree of proximity between the development on land that is not within a residential zone and land in a residential zone. The test established by that provision requires that the land on which the development is proposed be directly opposite land in a residential zone and be on the other side of a road with a reserve of 18m or less in width. In my opinion, the test laid down in regulation 14(3)(d)(ii) has a significant bearing on the meaning to be accorded to the word “adjacent” as appears in the immediately preceding regulation. Regulation 14(3)(d)(ii) was clearly meant to do some work. The proximity test in regulation 14(3)(d)(ii) was intended by the legislative draftsman to act upon and influence the meaning of the word “adjacent” in regulation 14(3)(d)(i). The clear legislative intent 2 D.J. Gifford and K.H. Gifford How to Understand an Act of Parliament, pp 116-117. See Davies v Western Australia (1904) 2 CLR 29. 11 was for the provisions of regulation 14(3)(d)(ii) to set the upper limit of the proximity of a development on non–residential land to land in a residential zone, and to read down and confine the meaning of “adjacent” - a word that is notorious for its imprecise and shifting meaning. It was intended that the word “adjacent” denote a degre e of proximity between the development on land that is not in residential land and land in a residential zone closer than that prescribed by regulation 14(3)(d)(ii). Accordingly, a development on land in a non residential zone (NR) is adjacent to land in a residential zone (R) if NR is closer or nearer to R than being directly opposite R and on the other side of a road with a reserve of 18m or less in width. One way of validating this conclusion is to ask the rhetorical question: if regulation 14(3)(d)(ii) was not intended to read down the meaning of the word “adjacent”, then why go to the trouble of prescribing an alternative specific test of proximity, whose scope of operation is limited by reference to topographical features and distances. The draftsman could have simply employed a single test of proximity predicated upon the condition of being “adjacent”. I suggest that the legislature chose not to do that because of the chameleon qualities of the word “adjacent”, and the difficulties that courts have ex perienced in the past in divining the meaning of “adjacent” in various contexts. Having reached the conclusion that the word “adjacent” denotes a degree of proximity closer than that delineated by the test in regulation 14(3)(d)(ii), it is not necessary for the purposes of this appeal to define with any greater precision the meaning of “adjacent” – though it would appear to include a number of degrees of propinquity such as “contiguous”, “adjoining” or “neighbouring”. When one has regard to the attached colour coded diagram it is clear that the subject development is further away from land in a residential zone (MD) than 12 being directly opposite such land and on the other side of a road with a reserve of 18m or less in width. The appellant has argued that the Tribunal should apply a purposive approach to the relevant third party appeal provisions, and in so doing should construe Regulation 14(3)(d)(ii) in accordance with the underlying purpose or object of the provision. The orthodox view was that the purposive approach to statutory interpretation should only be applied when an attempt to apply the literal approach produces an ambiguity or inconsistency: see Meeking v Mills (1990) 169 CLR 214 at 235. In my view, the relevant provisions do not give rise to an ambiguity or inconsistency. However, I accept the modern tendency to prefer the purposive approach over the literal approach, 3 and to apply the purposive approach even when the meaning of the statute is clear on its face. Although Regulation 14(3)(d)(i) and (ii) is clear on its face, that does not preclude a purposive approach being taken to the construction of the relevant provisions: see K.P. Welding Construction Pty Ltd v Herbert (1995) 102 NTR 29 at 40-41; Peninsula Group Pty Ltd v Registrar– General of the NT (1996) 136 FLR 8 at 12. The purposive approach to statutory interpretation is encapsulated in s 62A of the Interpretation Act (NT): In interpreting a provision of an Act a construction that promotes the purpose or object underlying the Act (whether t he purpose or object is expressly stated in the Act or not) is to be preferred to a construction that does not promote the purpose or object. The objects of the Planning Act are set out in s 2A of that statute. In my opinion the literal construction I have imposed on Regulation 14(3)(d) See Cole v Director –General of Department of Youth and Community Services (1987) 7 NSWLR 541 at 549 per McHugh JA. 3 13 is consistent with both the underlying purpose or object of the Act. Furthermore, the combined operation of s 117 of the Planning Act and Regulation 14(3)(d)(i) and (ii) evinces a clear legislative intent to significantly restrict the scope of third party appeals. The literal construction placed on Regulation 14(3)(d)(i) and (ii) promotes that object or purpose. A question that arises in these proceedings is whether it is permissible for the Tribunal to have recourse to the second reading speech in relation to the third party appeal provisions. S 62B(1) of the Interpretation Act (NT) sets out the circumstances under which it is permissible to have regard to extrinsic material such as a second reading speech: In interpreting a provision of an Act, if materia l not forming part of the Act is capable of assisting in ascertaining the meaning of the provision, the material may be considered – (a) to confirm that the meaning of the provision is the ordinary meaning conveyed by the text of the provision taking into account its context in the Act and the purpose or object underlying the Act; or (b) to determine the meaning of the provision when – (i) the provision is ambiguous or obscure; or (ii) the ordinary meaning conveyed by the text of the provi sion taking into account its context in the Act and the purpose or object underlying the Act leads to a result that is manifestly absurd or is unreasonable. In my opinion, Regulation 14(3)(d)(i) and (ii) is neither obscure nor ambiguous; and therefore it is not permissible to resort to the second reading speech pursuant to s 62B(1)(b)(i). Nor is s 62B(1)(b)(ii) activated. However, it is permissible to consider the second reading speech to confirm that the meaning of the provision is the ordinary meaning conveyed by the text of the provision taking into account its context in the Act and the purpose or object underlying the Act. In performing 14 that exercise the Tribunal must not allow recourse to the second reading speech to alter its interpretation of the provision, should the speech indicate a different construction of the provision. 4 In my opinion, the contents of the second reading speech confirm that the meaning of the provision is the ordinary meaning conveyed by the text of the provision taking into account its context in the Act and the purpose or object underlying the Act. In the second reading speech, Dr Burns said: A key commitment by government was to introduce limited rights of third party appeals. These are appeals by parties other than the appl icant such as neighbours. Dr Burns went on to say that appeals will not be permitted in a nonresidential zone unless it is on land that interfaces with residential zoned land. The use of the word “interfaces” is illuminating. That word connotes a common point or boundary between two things. That element of connectivity is entirely consistent with the construction placed on Regulation 14(3)(d)(i) and (ii) by applying both the literal and purposive approach to statutory interpretation. Conclusion For the above reasons I find that the appellant does not have a right of appeal pursuant to the third party appeal provisions of the Planning Act and Planning Regulations. In due course I will hear the parties on the question of costs. 4 See Australian Federation of Construction Contractors; Ex parte Billing (1986) ALR 416 at 420. 15 Dated this 5 th day of December 2008 ………………………… Dr John Allan Lowndes Chairperson of the Lands Planning and Mining Tribunal 16 17