Planning Fees - Municipal Association of Victoria

advertisement

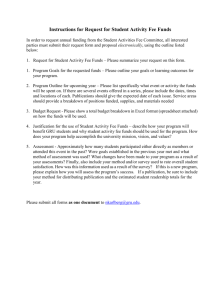

PLANNING FEES INTRODUCTION The issue of the regulation of planning fees is complex and involves several challenges. This paper provides an overview of these challenges to further inform the MAV response to this issue. The Department of Sustainability and Environment has commenced a process to review planning fees. The first stage in this process is to develop an understanding of the data required to conduct a review. A full review must be completed by 2010, when then current regulations specifying fee sunset. Planning fees have declined in real value since the last review in 2000. Between 2000-01 and February 2006, there was no adjustment to the quantum of the fees in line with inflation. This is in direct contrast to the automatic adjustments to State Government fees, which occurs under the Monetary Units Act 2004 (although no retrospective increase was applied). The failure to index the fees has reduced the revenue collected by councils through the planning fee structure by approximately 10 per cent over the five years to February 2006 and has resulted in an increase in the contribution of ratepayers to the planning system. There are a number of options available to local government for planning fees. Endorsing or advocating for many of these options entail a risk to local government. The purpose of this paper is to examine the risks and make an initial assessment of the viability of options available to the sector. The MAV has limited data on the cost of undertaking planning work (conducted using data nearly a decade old) which suggests that the main determinant of costs in assessing planning applications is the complexity of the application. This complexity is typically measured by whether the application receives objections and the extent to which ongoing dialogue between the applicant and the planning unit occurs. The case studies suggest that a rational approach to determining planning fees may result in an increase in the fees paid for applications for small development and a reduction in the fees for large development applications if alignment of fees with costs is the single principle underpinning the setting of fees. Consequently, local government should exercise some caution when assessing the costs and benefits of advocating for a review of planning fees. Annual increases in planning fees in line with inflation are practically feasible. An adjustment in line with inflation was made in February 2006, and another is planned for July-August 2006. Advocating for significant increases in fees or a review of fees is less appealing in the current political environment. Previously the MAV sought a review of the fees charged for higher value applications which are low, relative to other states. CURRENT PLANNING FEES The legislative provisions that empower planning fees are appropriately broad and allow significant flexibility in the application of different fee classes and fee levels. The Planning and Environment Act 1987 allows regulations to prescribe fees for a range of activities undertaken by local or state government. Fees may be prescribed for: a) b) c) d) planning certificates; considering applications for permits; considering applications for certificates of compliance; amendments to the planning scheme (including, not limited to the following) (i) considering proposals for amendment; and (ii) any stage in the amendment process; and (iii) considering whether or not to approve the amendment; and e) giving notice of permit applications; and f) determining whether anything has been done to the satisfaction of a responsible authority, Minister, public authority, municipal council or a referral authority; and g) providing maps showing the location of boundaries in a planning scheme. The fees for amendments to permits has just come into effect, after a regulatory impact statement was completed in late 2005, based on the same methodology and assumptions underpinning the 2000 fees. In addition, the Act allows for the prescription of fees for different classes of developments. There is no requirement to prescribe fees for any of the above activities. The Planning and Environment (Fees) Regulations 2000 prescribe the current fee structures. The fee levels are prescribed in dollar amounts rather than fee units. In July 2000, planning fees were amended in Victoria under the Planning and Environment (Fees) Regulations 2000. These regulations resulted in a change to the structure of the fees and a significant increase in the value of the planning fees. Planning fees remained static between July 2000 and January 2006, at which time the Minister for Planning introduced a 2.4 per cent increase in regulated fees. An assessment of the Melbourne consumer price index between July 2000 and January 2006 indicates that general costs increased by approximately 14 per cent versus an increase in the regulated fee of 2.4 per cent. The MAV has undertaken a survey of its member councils to establish the approximate loss of planning fee revenue due to regulated planning fees not being increased in line with the consumer price index. The study indicated that there is an approximate cumulative loss of $4.6 million for 38 councils1 due to the gradual erosion of the value of planning fees. The current fees have never fully covered costs. Even with the introduction of indexation, an annual cost to local government of approximately $1 million (across the 38 councils) will be borne by ratepayers. 1 While it was found that that number of planning applications was a good estimator of planning fee revenue (R²=0.83), there was insufficient data to estimate the shortfall of all councils across the survey period. Based on this simple predictor and the number of planning applications for 2003-04, it was estimated that the 41 remaining councils increased the undercollection by 72.5 per cent. Consequently, the cumulative under collection is estimated to amount to $8 million and approximately $1.7 million per annum if indexation was introduced. PRINCIPLES UNDERPINNING A PLANNING FEE SYSTEM Public good Any assessment of the value of planning fees inherently considers the public value created by planning regulation. That is, through the regulation of the planning system, the community also obtains a benefit through the creation and administration of planning controls. From this perspective, if planning fees seek to cover the costs borne by local government, the fee should only cover the private benefit gained by the applicant and the wider community should contribute the public good component. This principle has been adopted into the current fees by specifying those activities undertaken during the planning application process deemed to provide public good and passing on full cost recovery except for the public good elements. In order to maintain the assessed divide between public and private benefit, it is necessary that the regulated fee incorporates an appropriate escalator. Optimally, this would be linked to an independent assessment of the increasing costs of planning in the sector. However, a more feasible option would be for annual increases linked to inflation. The lack of escalation of planning fees has meant that the distribution of public good components of the planning system and private good components has been blurred since the 2000 review (which used data from 1997-98). Cost recovery While it appears axiomatic that planning fees be determined based on cost recovery, several conceptual issues calls this into question. Prima facie, this model has inherent attraction for a public sector agency – fees can be minimised and remain proportional to the actual cost of delivering the service. In addition, this approach could overcome the developers’ criticisms of the current fee structure and their value which has only limited connection between the cost of the service and the quantum of the fee. Many applications for large developments are likely to be easier to assess because trained planning professionals have produced the application and are the contact for the planner. This is not the case for the majority of applications, often for smaller developments, where individual applicants interact with the planning system, frequently for the first and last time. A cost recovery approach would shift the value of planning fees from the significant developers to the small residential developers and have no regard to the value of the works proposed, or benefit derived from those works. Based on the limited analysis conducted to date, a cost recovery model would result in a reform to the fee structure, with the fees for significant developments aligning to the actual cost of provision and not inflated due to their willingness and capacity to pay higher fees. This would remove the current suspected cross subsidisation of the smaller developments from the large developers and reduce the ability of councils to recover costs. Changes to planning activities The planning functions of local government have changed significantly over time, with greater requirements for strategic planning policy work. This wider function of councils benefits both planning applicants and the broader community, yet the current planning fee structure fails to address these costs. The strategic planning activities of councils are more difficult to clearly apportion to the cost of assessing a planning application. Distortion of market behaviour The imposition of fees has a significant capacity to distort the behaviour of individuals and the wider community (in fact, this is often the primary purpose of a fee or tax). In the context of planning fees, placing increased costs on certain applications may strongly distort development across Victoria. It is likely that the distortion will be related to the benefit derived from the activity and the sensitivity of the development to increased costs. For example, a mum and dad developer seeking a permit to build a shed may be significantly affected by any increases in planning fees, whereas fees for a multimillion dollar development would be likely to have less ability to distort behaviour. High fees may double to cost of undertaking the development work in the former case but in the latter increase costs extremely moderately. This perspective is supported by previous studies which examined the willingness of large scale developers to pay higher fees for greater certainty of planning assessment and a reduction in the times taken of planning system. Capacity and willingness to pay Classical microeconomic theory argues that prices are determined by the supply and demand of a good. This theory postulates that if the price is set at the optimum point, there will be a number of individuals willing to pay a higher price for the good which indicates that the product is more valuable to that particular person or organisation. For example, a private large scale developer may value securing a planning permit for their proposed development in a timely fashion as far more than a smaller developer or vice versa. For these consumers, there may be a very strong case that they would be willing and able to pay a considerable sum to make a planning application that will be dealt with effectively, efficiently and predictably. This perspective would argue that there is considerable merit in the current fee structure by creating a strong nexus between the capacity and willingness to pay, value of the works (as a proxy for willingness to pay), and the fee structures. The capacity and willingness of developers to pay may be assessed by the use of proxies such as the value of the development. This perspective contrasts with a model based solely on cost recovery as outlined above and may provide a more acceptable model to the clients of the planning system. PROCESS FOR INCREASING REGULATED FEES Regulated fees – not just planning fees – can be increased through changes to legislation, regulation or by specifying the value of fees in fee units. The processes of each are considered in turn. Legislative changes Regulated fees are typically specified in an act of parliament or regulation made under an act of parliament. Specification of fees in legislation will create a structure that is the most difficult to alter at a later stage. In addition, it will require a significant and sustained project to be undertaken which would increase the timelines involved and the costs borne by stakeholders in negotiating changes. Given the current legislative provisions broadly empower regulations to specify the fees, there appears to be little reason to advocate for legislative change. Regulatory changes Pursuant to s.7 of the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994, a regulatory impact statement must be prepared for proposed new regulations and regulatory changes. An independent party must prepare the regulatory impact statements, which assess the costs and benefits of regulatory changes. An overview of the regulatory impact statement is provided in Appendix 1. Specific exemptions exist for a number of areas. Section 8(1) (a) provides that regulatory impact statements are not required when: the proposed statutory rule increases fees in respect of a financial year by an annual rate that does not exceed the annual rate approved by the Treasurer in relation to the State Budget for the purposes of this section The annual rate is typically the consumer price index as specified in the budget papers. In addition, s.8(2) provides a further exemption if the fee increase is above the rate approved by the Treasurer if it otherwise complies with s.8(1)(a) but has been rounded to the nearest dollar. This indicates that fees can increase by inflation on an annual basis by the responsible Minister if they are prescribed in regulations without needing to complete a regulatory impact statement. The Subordinate Legislation Act 1994 requires that regulatory impact statements include the following information: a) a statement of the objectives of the proposed statutory rule; b) a statement explaining the effect of the proposed statutory rule, including in the case of a proposed statutory rule which is to amend an existing statutory rule the effect on the operation of the existing statutory rule; c) a statement of other practicable means of achieving those objectives, including other regulatory as well as non-regulatory options; d) an assessment of the costs and benefits of the proposed statutory rule and of any other practicable means of achieving the same objectives; e) the reasons why the other means are not appropriate; f) any other matters specified by the guidelines; g) a draft copy of the proposed statutory rule. The regulations go on to require the assessment to consider the economic, social and environmental effect of the regulation and the compliance and administration costs. The Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (VCEC) is empowered to assess the validity of the regulatory impact statements pursuant to the State Owned Enterprises (State Owned Body – Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission) Order 2003. This Order in Council provides that the VCEC will: review the quality of business impact assessments and regulatory impact statements having regard to relevant guidelines issued from time to time by the Government, and provide comment on these assessments and statements to the Department of the Minister responsible for the proposed legislation. In short, the legislative framework for regulatory impact statements requires an extensive assessment of the purpose, options, costs and benefits of proposed regulatory changes. The VCEC has a gatekeeper role in assessing regulatory impact statements and has the capacity to block their progress (unless the Minister provides an exemption). Any significant changes made to the planning fees will require a regulatory impact statement to be completed. No regulatory impact statement will be required if annual adjustments are made to the fees in line with inflation. State Government Fee Indexation The Monetary Units Act 2004 specifies that the value of fee units increases in line with inflation, as determined by the Treasurer. This Act was introduced to automatically increase specified fees, fines and charges to ensure they maintain their value, although no retrospective increases in the value of fees or penalties were introduced. In the second reading speech, the Treasure enunciated the key purpose of this Act: This legislation implements the government’s policy of automatic indexation as announced in the 2003–04 budget. This initiative will ensure that the original intent in setting fees and fines is maintained over time.2 (Emphasis added) It is illustrative that in introducing the Monetary Units Act, the State Government clearly made choices about the value of indexation for certain prescribed fees. The Act made a number of amendments to fee and penalty values prescribed in other legislation to convert them to fee units (the equivalent of $10 upon commencement of the Act) and penalty units (the equivalent of $100 upon commencement of the Act). 2 John Brumby (2004), Victorian Assembly Hansard, Monday 4 March 2004, p300 The views of Bob Stensholt, Member for Burwood provide some guidance on how the State Government made this determination: A number of fees, fines and penalties will not be automatically indexed: those which are less than $10 and those to the value of less than 0.1 of a penalty unit, which is also $10; fees and penalties subject to price determination regimes established under the Essential Services Commission Act; fees and penalties set by corporatised or privatised entities; and fees and penalties subject to national agreements or regimes — an example of this in the bill is the Petroleum (Submerged Lands) Act, which is covered by a national regime and so is not automatically indexed. Other fees and penalties which will not automatically be indexed are those set by self-funding statutory authorities.3 It would appear from this list of exemptions that local government would fit into the last category: that of a self-funding statutory authority. From this perspective, there is prima facie evidence that the State Government has made a deliberate decision to not automatically index the value of planning fees from 1 July 2004. OPTIONS Incremental adjustments An incremental approach which will see planning fees increased in line with inflation progressively is an option. The Minister for Planning could introduce amendments to the regulations (as he did in January 2006) on an annual basis without the requirement to undertake a regulatory impact statement. In order to achieve this outcome, the MAV could either seek adjustments annually and attempt to delay the review of planning fees until closer to 2010 or to advocate for this option if a full review was undertaken. Retrospective increase in planning fees Local government could seek a retrospective increase in the value of planning fees to ensure that the July 2000 value is restored. This could be combined with annual increments in line with inflation to ensure that the real value of the fees are maintained. Local government would effectively need to argue that the data collection and methodology established at the previous review is still relevant to obtain a successful outcome. However, it is clear that this would require a full regulatory impact statement process before it could be implemented. New planning fee regime 3 Bob Stensholt (2004), Victorian Assembly Hansard, Wednesday, 31 March 2004, p407 The Department for Sustainability and Environment has commenced a review of the planning fee structure, including the fee values and the appropriate classes of fees. This approach would review and establish, from a zero base, the principles which should underpin the planning fee system. A review will present a number of threats to local government planning fee revenue. The current planning fees increase with the value of the development. However, several case studies conducted by the MAV suggests this approach does not reflect the actual cost of delivering the service – that is, the primary drivers of costs in assessing planning applications stems from the complexity of the application rather than the project’s value. Despite this threat, a holistic review will also provide the sector with a number of opportunities to incorporate additional features into the calculation of planning. As outlined above, the functions and activities of councils in planning has changed significantly in recent times with a much greater emphasis on strategic planning. A review provides an opportunity to advocate for a planning fee structure which incorporates strategic planning activities. The public good of the planning system can also be reviewed to ensure that the proportion of cost recovery from applicants is sufficient. This provides an opportunity to redress the blurring of the public good/private good divide caused by the lack of escalation of the current planning fees. CONCLUSION The State Government is constrained in its ability to respond to the local government sector’s concerns about the current value of planning fees by its requirement to conduct a regulatory impact statement which is then submitted to the VCEC. The legislative framework to increase the value of fees introduces an extremely complex procedure unless annual increments are limited to inflation. In the lead up to an election in November 2006 in which the annual increase in the state fees and fines will almost inevitably become an issue (particularly around traffic infringements), it may not be politically feasible for retrospective increases in fees to be adopted nor would a holistic analysis of alternative fee structures be of value. The MAV has been lobbied by its member councils to undertake advocacy for a retrospective increase in the value of planning fees. This would result in approximately a 10 per cent increase in the planning fees across the board as previously outlined. There is considerable risk for the local government sector in pursuing a full review of the planning fee system as it is possible that the review would adopt different principles – a cost recovery system – for the planning fee structure, which could result in significant increases for applications for low valued developments and a reduction in applications for high valued developments. As previously discussed, one of the most contentious areas in the determination of planning fees is the balance of costs borne by the community (ratepayers) and the costs borne by the developer (or instigator of action). Another contentious element that would be discussed during a review of planning fees would be the basis for deciding the fee classes and the quantum of fees in each class. There will be an inherent tension between fees set though an assessment of the capacity and willingness of applicants to pay, taking into account the benefit derived and value of the works, versus a fee structure aimed at simply apportioning fees based on the actual cost of the planning activity. Previous analysis of the costs borne by councils in assessing planning applications indicates that the key cost driver is the complexity of the application rather than the value or type of development.4 Complexity often relates to those applications that receive objections or which require amendment and they cost significantly more to process than simple or high quality and uncontentious applications. Given that both a retrospective fee increase to their real 2000 value or a full review will result in similar regulatory impact statements, it is likely that the State Government prefer the latter option. There MAV therefore needs to balance the views of its members carefully against the risks associated with advocating for either a full review of planning fees or increases in planning fees above the rate of inflation. 4 Based on MAV costing studies for two councils APPENDIX 1: FLOW CHART FOR THE REGULATORY IMPACT STATEMENT