EC - Hormones (AB) - WorldTradeLaw.net

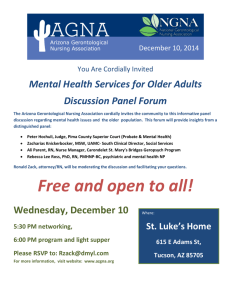

advertisement