Chronic Training Adaptations - Wikispaces

Chronic Training Adaptations

Exercise or training regularly over an extended period of time (3 times per week for 6-8 weeks) leads to the development of long-term or chronic adaptations to training. Evidence of these adaptations can occur at various stages

Once achieved, these adaptations are retrained unless training ceases.

Upon cessation, the body will gradually revert to its pre-training condition

(de-training).

Unlike acute responses to exercises, chronic adaptations to training vary greatly and are dependant upon:

Type and method of training undertaken – aerobic vs anaerobic training. Chronic responses are very specific to the type of training performed.

The frequency, duration and intensity of the training undertaken – the greater these things, the more pronounced the adaptations

The individual’s capacities and hereditary factors (genetic make-up)

Chronic Adaptations to Aerobic (endurance) Training:

Minimum period is 6 weeks

More evident over 12 weeks

Adaptations occur at both tissue and system levels.

Cardiorespiratory Adaptations to Aerobic (endurance) Training

Chronic cardio-respiratory adaptations are primarily designed for more efficient delivery of larger quantities of oxygen to working muscles.

They decrease cardiovascular disease (CVD)and other health-related illnesses.

Cardio-respiratory adaptations are best developed through continuous, fartlek and longer interval type training.

Cardiovascular Adaptations:

Cardiac hypertrophy (increased ventricular volume):

Enlargement of the heart muscle itself

Increase in size and volume of the ventricular chambers, particularly the left ventricle occurs.

Significantly increases stroke volume

Increased capillarisation of the heart muscle:

Increase in capillarisation of the heart muscle itself (Increase in capillary density and blood flow to the heart muscle)

Increased supply of blood and oxygen allows the heart to beat more strongly and efficiently during rest and exercise

Coronary protective benefit (therefore decreased risk of heart attack)

Increased stroke volume of the heart:

Heart ejects a greater volume of blood with each beat

Stroke volume is greater at rest, during sub-max and max workloads for a trained athlete compared to an untrained person

Eg. Average stroke volume at rest:

Untrained male - 70-80millilitres/beat,

Trained male endurance athlete -

100millilitres/beat or more.

During maximal exercise:

Untrained person – 110 millilitres/beat

Trained person – 130 millilitres/beat

Elite endurance athletes – 190 millilitres/beat

Trained and untrained females have lower stroke volumes than their male counterparts under all exercise conditions, mainly due to a smaller heart size

Lower resting heart rate:

The amount of oxygen required by an individual at rest does not alter as a result of their training status.

At rest, it takes about 5 litres of blood per minute (cardiac output) to circulate around the body to supply the required amount of oxygen to the body cells

Cardiac output (Q) is equal to stroke volume (SV) multiplied by heart rate

(HR).

Q = SV x HR

However, if an individual has developed a greater stroke volume, the heart does not have to beat as frequently to supply the required blood flow

Eg.

Before training:

Q = SV x HR

5L/min = 70 mL/beat x 71 beats/min

After training:

Q = SV x HR

5L/min = 100 mL/beat x 50 beats/min

This is why resting heart rate is a useful indicator of aerobic fitness.

Lower resting heart rate – greater level of aerobic fitness

Elite – 35bpm (marathon runners, triathletes, distance swimmers)

Average adult male – 70bpm

Lower heart rate during sub-maximal workloads:

Mainly a result of increased stroke volume.

The heart works more efficiently - (More blood is pumped with each beat, and therefore the heart doesn’t have to work as hard to supply the required blood flow and oxygen supply)

Slower increase in heart rate during exercise and a lower and faster attainment of steady state during exercise

Improved heart-rate recovery rates:

Heart rate of a trained athlete will return to pre-exercise levels (resting rate) in a much shorter time than that of an untrained individual.

Increased cardiac output at maximum workloads:

Cardiac output – unchanged at rest and even during sub-maximal exercise regardless of training status. Does increase during maximal exercise.

Maximal exercise – may increase to values of:

20-22 litres per minute for untrained male

15-16 litres per minute for untrained females

30 litres per minute or more – highly trained athletes

Lower blood pressure:

May lower blood pressure, especially among people who suffer from hypertension (high blood pressure)

Systolic and diastolic pressure levels may decrease during both rest and exercise

Helps to reduce resistance to blood flow and reduces strain on the heart, thereby decreasing the risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular conditions

Increased arterio-venous oxygen difference (a-VO2 diff):

Trained individuals are able to absorb more oxygen from their bloodstream into their muscles during exercise performance compared to untrained subjects.

This is due to:

Increased muscle myoglobin stores

Increased number and size of mitochondria within their muscles

As a result of this, the concentration of oxygen within the venous blood is lower

Subsequently the arterio-venous oxygen difference is increased during both sub-max and maximal exercise

Therefore, and increased arterio-venous oxygen difference (a-VO2 diff) indicates a greater uptake of oxygen by the muscles with trained individuals

Increased blood volume and haemoglobin levels:

Total blood volume may rise by up to 25% (from 5.25L to 6.6L) for an average adult male with regular and sustained aerobic training.

Red blood cells may increase in number and the haemoglobin content and oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood may also rise.

Increased capillarisation of skeletal muscle:

The average number of capillaries supplying each muscle fibres is:

5.9 for trained athletes

4.4 for untrained athletes

Changes to blood cholesterol, triglycerides, low- and high-density lipoprotein levels:

Results may include a decrease in blood cholesterol levels, triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein (LDL).

These substances are associated with the development of coronary heart disease.

Aerobic training increases the ratio of high-density lipo-protein (HDL) to low-density lipoprotein.

High-density lipoprotein is thought to provide a coronary protective effect, lessening the risk of developing coronary heart disease.

Respiratory Adaptations

Increased lung ventilation:

More efficient and improved lung ventilation

At rest and during sub-maximal exercise, ventilation may be reduced due to improved oxygen extraction

However, during maximal workloads, ventilation is increased because of increased tidal volume (amount of air breathed in and out in one breath) and respiratory frequency (the number of breaths taken per minute).

Pulmonary diffusion (the ability of the blood to extract oxygen from the alveoli) is also enhanced.

Increased maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max)

Increase in the maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max) during maximal exercise

Improvement can be between 5–30% following a regular and sustained training program

This occurs because of adaptations such as:

Increased cardiac output

Increased red blood cell numbers

Increased a-VO2 difference

Increased muscle capillarisation

Greater oxygen extraction by the muscles

Increased anaerobic or lactate threshold

As a result of the adaptations that improve oxygen delivery and utilisation in the muscles, a higher lactate threshold (the point at which oxygen supply cannot keep up with oxygen demand) is developed.

Advantage:

The anaerobic glycolysis (lactic acid) system is not utilised as much until higher exercise intensities are reached.

Consequently, lactic acid and hydrogen ion accumulation will be delayed until these higher work-load intensities are attained

The athlete can “work harder and for longer periods”

Muscle Tissue Adaptations to Aerobic (Endurance) Training:

Chronic aerobic training adaptations within muscular tissue are best produced through continuous training or high-repetition resistance training

The following tissue-level changes can be observed within skeletal muscles following extensive endurance training:

Increased oxygen utilisation:

Aerobic training enhances the body’s ability to attract oxygen into the muscle cells and then utilise it to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for muscle contraction

This process occurs in the following ways:

Increased size and number of mitochondria –

Mitochondria are the site of ATP synthesis and where glycogen and triglyceride stores are oxidised

(Greater oxidisation of fuels to produce ATP)

Increased myoglobin stores – Myoglobin is the substance in the muscle cell that attracts oxygen from the bloodstream into the muscle. (Increase ability to extract oxygen)

Increased muscular fuel stores:

Increase in the muscular storage of glycogen, free fatty acids and triglycerides, along with the oxidative enzymes required to metabolise these fuel stores and produce ATP.

Increased oxidation of glucose and fats:

The muscular adaptations result in an increase in the capacity of muscle fibres to oxidate both glucose and fats

The capacity of the aerobic system to metabolise these fuels is increased

Increased oxidation of fats as a fuel source; due to:

Increased storage of triglycerides and free fatty acids

Increased levels of enzymes associated with fat metabolism

Means that:

At any given exercise intensity, a trained individual has to rely less on glycogen, thereby “sparing” glycogen stores (Glycogen sparing)

Therefore delaying the time to exhaustion due to glycogen depletion.

Decreased utilisation of the anaerobic glycolysis (lactic acid) system:

The enhanced capacity of the muscles to aerobically metabolise glucose and fats and other muscular level adaptations also means that there is less reliance upon the anaerobic glycolysis system to produce energy for ATP resynthesis until higher exercise intensities are reached.

Allows athletes to work at higher intensities without exceeding

OR lactate threshold.

Aerobic training results in an increase in the lactate threshold

Eg. An athlete must run at a faster pace in order to accumulate the same amount of blood lactic acid as before training

Muscle-fibre type adaptation:

Some research has shown evidence that skeletal muscle switches fibre types from fast twitch to slow twitch as a result of endurance training.

Skeletal muscle fibres are classified into three types:

Type 1 – Slow-twitch oxidative fibres:

Contain large amounts of myoglobin, and large numbers of mitochondria and blood capillaries.

Red

Split ATP at a slow rate

Slow contraction velocity

Very resistant to fatigue

High capacity to generate ATP by oxidative metabolic processes.

Type 2A – Fast-twitch oxidative fibres:

Contain an extremely large amount of myoglobin, and huge numbers of mitochondria and blood capillaries.

Red

Very high capacity for generating ATP by oxidative metabolic processes

Split ATP at a very rapid rate

Fast contraction velocity

Resistant to fatigue

Type 2B – Fast-twitch glycolytic fibres:

Contain low myoglobin content, relatively few mitochondria and blood capillaries, and large amounts of glycogen

White

Geared to generate ATP by anaerobic metabolic processes

Fatigue easily

Split ATP at a fast rate

Fast contraction velocity

Individual muscles are a mixture of the three types of muscle fibres, but their proportions vary depending on the action of the muscle and the genetic make-up of the individual

Summary of muscle tissue adaptations to aerobic (endurance) training:

Before Training After Training

Mitochondria (size and number) Increased

Glycogen Stores

Myoglobin

Triglyceride Stores

Oxidation (both glucose and fats)

Increased

Increased

Increased

Increased

Anaerobic Glycolysis (lactic acid system) Decreased

Muscle Type Adaptation (number and type)

Increased

Some conversion of:

Type 2B fibres to

Type 2A fibres

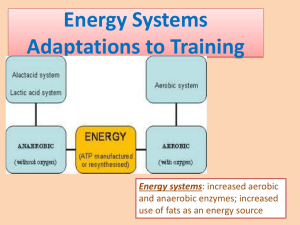

Chronic Adaptations to Anaerobic Training

Anaerobic training effects are best developed through sprint training, shorter and faster interval training, plyometric training, circuit training, and resistance (strength and power) training.

The greatest adaptations occur at the muscle-tissue level. They include:

Muscle hypertrophy:

Significant enlargement of muscle fibres (mainly

Type 2B fast-twitch fibres) resulting in muscular hypertrophy (an increase in the cross-sectional size of the muscle) and subsequently, greater strength

Hypertrophy occurs as a result of an increased size and number of myofibrils per muscle fibre and increased amounts of myosin and actin myofilaments

Muscular hypertrophy is more pronounced in males than females due to greater levels of testosterone.

Increased muscular stores of ATP and PC:

Muscular hypertrophy is accompanied by increased muscular stores of

ATP and PC, as well as enzymes required to break down and resynthesise ATP

Increased capacity of the ATP-PC system – greater energy release and faster restoration of ATP

Benefits athletes in activities that require speed, strength and power

Increased glycolytic capacity:

Enhanced muscular storage of glycogen and increases in the levels of glycolytic enzymes.

Capacity of the anaerobic glycolysis system to produce energy is enhanced

Cardiac hypertrophy:

Most significant circulatory system adaptation resulting from anaerobic training

Increase in heart muscle size

Anaerobic training produces an increase in the thickness of the ventricular walls

No change in stroke volume, however there is a more forceful contraction.

Other anaerobic training adaptations:

Increase in the strength and size of connective tissues such as tendons and ligaments

Increase in the number of motor units recruited for maximum contractions

Increase in the speed of nerve-impulse transmission to the muscle cells and increase in the speed of muscular contraction

Summary of Chronic Adaptations to Training:

Tissue of

System Level

Specific Adaptation to Types of

Training

Rest

Submaximal exercise

Maximal

Exercise

Circulatory

System

Aerobic Training

Cardiac Hypertrophy – increase in size of ventricular cavities

Increased capillarisation of the heart muscle

Increased stroke volume

Lower resting heart rate

Lower heart rate during submaximal workloads

Improved heart-rate recovery rates

Increased cardiac output at maximum workloads

Lower blood pressure

Increased a-VO2 difference

Increased capillarisation of skeletal muscle

Respiratory

System

Muscle

Tissue

Changes to blood cholesterol, triglycerides, low and highdensity lipoprotein levels

Anaerobic Training

Cardiac hypertrophy – increase in thickness of ventricular walls

Aerobic Training

Increased lung ventilation

Increased VO2 max

Increased lactate threshold

Aerobic Training

Increased oxygen utilisation

Increased size of mitochondria

Increased myoglobin stores

Increased muscular fuel stores

Glycogen

Triglycerides

Free Fatty Acids

Oxidative Enzymes

Increased oxidation of fats

Decreased utilisation of the anaerobic glycolysis system

Muscle-fibre type adaptations

Anaerobic Training

Muscle hypertrophy

Increased number of myofibrils

Increased size of myofibrils

Increased amounts of myosin and actin filaments

Increased capacity of the ATP-

PC system

Increased stores of ATP

Increased stores of PC

Increased glycolytic capacity

Increased storage of glycogen

Increased levels of glycolytic enzymes

Increased speed and force of contraction