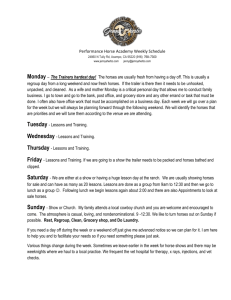

Nutritional Treatment of Equine Cushings and Laminitis

advertisement

NUTRITIONAL TREATMENT OF EQUINE CUSHING'S DISEASE AND LAMINITIS Joyce C. Harman DVM, MRCVS Madalyn Ward DVM Abstract Equine Cushing's disease is a relatively common and complex condition that is difficult to treat with conventional medicine. Cushing's disease involves a hyperplasia or adenoma of the anterior pituitary gland. Biochemical alterations include increased endogenous cortisol, insulin resistance, elevated adrenocorticotrophic hormone and decreased thyroid hormone levels. Symptoms include hirsutism with no loss of the winter coat in the summer, refractory laminitis, weight problems (over-or underweight), polyuria/polydipsia (Pu/Pd), frequent infections, lowered immunity to intestinal parasites, decreased intestinal wall integrity and infertility. A common and often fatal complication is laminitis (an inflammation of the laminae of the foot) that tends to be refractory to conventional treatment. One of the most common therapies used is phenylbutazone, an NSAID known to cause significant changes in the permeability of the intestinal wall. Recent research has shown that an intestinal bacterial exotoxin is one of the triggering factors in laminitis. By removing the phenylbutazone, healing the intestinal wall, many cases of laminitis become responsive to treatment. Correct hoof-care combined with nutritional management and the application of other modalities including acupuncture, Chinese and western herbs complete the healing process. The successful treatment of equine Cushing's disease is one of the best examples of treating a disease using the holistic approach. Each case requires different combinations of modalities, yet the outcome is usually positive with individually selected treatments. Introduction Cushing's syndrome in horses is being diagnosed with increased frequency. It has been in the horse population for many years, but generally went unrecognized. Cushing's actually appears to be increasing in frequency, in part to a better understanding of the diagnostic tests involved. Symptoms of Cushing's such as unexplained laminitis cases occurring in the winter or early spring and older horses with hursitism have been present for many years. However, it appears to these authors and others that the incidence is increasing and that the condition is being seen in younger horses. Laminitis is one of the more frustrating complications of Cushing's disease to treat in equine practice. Chronic cases can take a significant amount of time and energy, and still have unsatisfactory results. Natural medicine provides another toolbox of treatments to help practitioners deal with both acute and chronic cases. One of the major factors in getting laminitic horses to heal is to support intestinal health and repair the basement membrane of the intestinal tract. Pollitt's landmark work discussed the effects of a bacterial exotoxin on the laminae of the foot.1 If, using natural medicine, the basement membrane of the intestinal tract can be strengthened, less exotoxin should be absorbed from the intestinal tract. The goal in natural treatment of Cushing's and Cushing's-based laminitis is to provide nutritional support to prevent and reverse damage from circulating free radicals, prevent further damage to and encourage healthy laminar attachments and return the horse's metabolism to proper balance. When managed correctly, with patience and attention to detail, most chronic cases can return to reasonable work. The poorly responsive cases can often be managed and kept relatively comfortable without the use of drugs. It is important to remember when treating laminitis with natural medicine to approach each case individually. It can be detrimental to any case to use multiple supplements or treatment modalities without carefully evaluating the case. Because a product is natural does not rule out harmful effects or the negative effects of using too many products and overloading the body. Refractory cases may require many products, however, they should not be used all at once. Pathophysiology of Cushing's disease It has been thought that as an almost normal part of aging horses get pituitary adenomas of the pars intermedia.2, 3 However, there are conflicting reports in the texts as to the prevalence of the true adenoma. Some sources feel that the actual adenoma is less common and that there is a hyperplasia of the pars intermedia instead.4, 5 Both adenomas and hyperplasia cause similar sets of symptoms, however, the hyperplasia, being a functional disturbance rather that a tumor may be easier to treat. Many horses respond well to treatment; these cases are probably more functional than cancerous. The pars intermedia has melanotropes, cells that normally use dopamine to process its beta endorphin hormones.3 In Cushing's horses the dopamine is not present, so the melanotropes produce a small amount of corticotrophin also which stimulates glucocorticoid production by the adrenal cortex. The normal negative feedback to decrease production of corticotropin does not work since the melanotropes in the pars intermedia do not have glucocorticoid receptors.6 So the corticotropin release continues endlessly. The pars distalis, which has glucocorticoid receptors, decreases its production of corticotropin. Normally the hypothalamus coordinates the activity of the pituitary gland through the secretion of peptides and amines.7, 8 Why Cushing's is occurring is not understood. Is it just a hyperplasia of the pars intermedia, or is it from loss of dopaminergic control by the hypothalamus? If so, what is causing the hyperplasia? One theory is that chronic stress could affect dopamine secretion by the hypothalamus, causing a loss of control of the intermediate lobe and leading to the development of hyperplasia.7 There are no clear answers at this point. Clinical signs The clinical signs most commonly associated with Cushing's syndrome in horses are hirsutism or long hair that does not shed out in the summer9, refractory laminitis, weight problems (over-or underweight), lethargy/poor performance, polyuria/polydipsia and hyperhydrosis [table 1]. 10 Many other symptoms appear in certain individuals, with some horses exhibiting very few clinical signs, while others have many. One of the most serious symptoms of Cushing's is laminitis, often with no outward reason for its occurrence. 9, 11 It is not uncommon to have some of the most refractory cases of Cushing's based laminitis to occur in the winter, an uncommon season for typical cases. Even the more common summer laminitis that appears to be caused by overeating of grass can be quite refractory to treatment, especially when other clinical signs of Cushing's are present. Many horses diagnosed with Cushing's are overweight and are very easy keepers, sometimes unable to eat more than a small amount of hay each day to try to control their weight. In some cases, horses who were previously easy keepers suddenly start requiring more food to maintain their body weight. The overweight horses generally have fat pads in specific places2, 9 and cresty necks. The fat pads are generally behind the shoulder blades, on each side of the tail and along the lumbar area, In addition, the fat on their body is often visibly lumpy. Some of the horses who are beginning to loose weight also maintain their fat pads despite the obvious weight loss. Diabetes along with polyuria/polydipsia (Pu/Pd) 12, 9 are seen occasionally.2,5 Pu/Pd can also be caused by the compression of the pars nervosa by the enlarging pars intermedia, causing a decrease in antidiuretic hormone production.5 Frequent infections of the skin or other organs occur 2, 6 probably due to the hypercortisolism and hyperglycemia 11, 12, 10 It is well known that increased levels of cortisol are immunosuppressive and that diabetics are prone to infections due to the high levels of sugar in their blood. Sluggish thyroid glands or thyroid dysfunction are common in horses yet it has been difficult to associate clinical signs with laboratory findings.13 Some of the conditions previously attributed to thyroid problems, such as muscle soreness are also part of the Cushing's syndrome.14 Colic9 and poor teeth, with multiple dental abnormalities have been reported as clinical signs associated with Cushing's disease.5 It is unclear in the western literature exactly what the connection of Cushing's to colic and poor teeth is, however they may be part of the general breakdown of the system. The literature also indicates these horses have lowered immunity to intestinal parasites.5, 7 The author's hypothesis for a cause of Cushing's-based laminitis may have to do with poor integrity of the gut wall since there is evidence of colic and poor immune system function in Cushing's horses. Preliminary intestinal function laboratory tests performed by one of the authors in horses indicate that Cushing's horses can have decreased intestinal wall integrity (Harman, unpublished data). Infertility occurs, possibly due to a disturbance of gonadotropin secretion in conjunction with the disturbance of the pars intermedia function.7 Examining the problem from a Chinese perspective, the Kidney Yang deficiency described below gives rise to infertility problems. When studying the disease from the Chinese medical perspective, one of the more common diagnoses for Cushing's disease is Kidney (KI) Yang deficiency. Many of the symptoms fit the classic signs of Kidney Yang deficiency such as sore back muscles, weakness, lassitude, increased clear urine, stocking up in the legs and infertility. 15, 16 Chronic illness from other sources can lead to KI Yang deficiency. Retention of Dampness from Spleen deficiency can affect the kidneys by obstructing the movement of fluids. Just old age contributes to the deficiency of Kidney Yang. Kidney Yang deficiency affects the digestive tract and can produce diarrhea.15 Diagnosis The most important diagnostic tool for identifying Cushing's as the primary problem, or as the cause of laminitis, is the history and clinical signs discussed above. A thorough physical exam may reveal some of the less obvious signs such as poor teeth and reproductive problems. The supporting lab work can be inconclusive, but can be helpful and should be performed if possible.2, 5, 8 Laboratory diagnosis Laboratory work can be very unrewarding in the Cushing's patient. Part of the problem is that in equine practice single blood samples are taken whenever the practitioner is at the farm, so there is little standardization of the timing of the samples. Many parameters used have diurnal variations and may change due to stress or other factors including the amount of exercise a horse has had before the blood was drawn. Elevated blood cortisol can indicate high levels of stress in the body. Is the high cortisol coming from the Cushing's or has the Cushing's come from chronic stress affecting the feedback system in the pituitary gland? Cortisol as a single sample appears to be an inaccurate test for Cushing's disease.10, 14 Resting insulin levels 17, ACTH 10, 18 and glucose are sometimes used. Most of the time a more useful diagnostic test is the ACTH stimulation test.19 The low dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDS) is perhaps the most often used4, 10. However, in holistic practice this author avoids using the LDDS and stressing the adrenals further. Some of these horses have insulin resistant hyperglycemia, which can be identified with a single insulin and glucose sample or an insulin/glucose tolerance test.6, 20, 21 Another possible test is the oral glucose absorption test.22 A thyroid panel can be done, however the single sample test usually performed in equine practice is little more than a window into thyroid function and rarely proves valuable, except in motivating the clients to work hard to improve a low test. 13 Some new laboratory profiles are being offered that combine certain tests taken at certain times of the day. These may be more accurate in positively diagnosing Cushing's disease, but research needs to be performed before these tests can be considered more accurate than those that are already available. While doing the other laboratory tests, a complete blood count (CBC) is advisable to help check the immune system status. Many horses seen in these authors' practices have low white blood cell (WBC) counts. The neutrophil and lymphocyte counts vary, with one or both contributing to the low WBC. A chemistry screen is also advisable since some of these horses have a variety of metabolic problems associated with their condition, including liver disease and chronic infections. Insulin resistance Many Cushing's horses have elevated insulin levels in their blood17 without concurrently raised or lowered glucose levels.14, 21, 23 A relatively new condition is being recognized in human medicine, currently called syndrome X.24 Syndrome X is a group of symptoms related to insulin resistance or hyperinsulinemia.25 The cells show an inability to transport glucose into them. Insulin resistance occurs in as much as 25% of the nondiabetic population.26 Cushing's syndrome in horses has some of the same characteristics as syndrome X 17, 27 has in people. Some of the specific symptoms are obviously different, however, the general seriousness of the metabolic derangements are very similar. The reason the insulin is elevated is that it is not able to get into the cells. Normally when a sugar or carbohydrate is eaten, the blood sugar levels increase, insulin is secreted by the pancreas, glucose is carried into the cells by the insulin and the blood sugar goes back to normal. In insulin resistance, the cell wall insulin receptors cannot transport glucose correctly.28, 29 People that are susceptible to syndrome X are frequently from a genetic type considered "thrifty"30 or in horse terms, "easy keepers."31, 32 In this type of individual, horse or human, the body is very efficient at storing fat for times of need, and in fact, if fed less, they often become more efficient at storing fat. In humans much of the fat stored from impaired glucose metabolism is distributed centrally, especially around the abdomen. Many horses store their fat in specific places; fat pads on their body and cresty necks. The treatment of people with Syndrome X using natural medicine incorporates many of the ingredients used when treating the Cushing's horses. The permeability of the cell walls to insulin is enhanced and nutrients are provided to help insulin and glucose pathways function better.26 The details are discussed below in the treatment section. Conventional medical treatment The accepted drug therapy for Cushing's disease and its related complications is pergolide mesylate.11, 5 Pergolide is an expensive, type 2 dopaminergic receptor agonist that works on the melanotrope cells in the pituitary gland. The drug replaces dopamine, so must be given for life, however, horses have been removed from the drug successfully in this author's experience. This drug seems to help for a period of time, but does not seem to be a permanent cure. Cyproheptadine is an anti-serotonin drug that seems to be partially effective, less expensive, but has no real scientific basis for its use, as serotonin does not play a role in Cushing's. Therefore the reasoning behind its use is anecdotal, and most horses that do respond only seem to get help for a year or two. It may act in a secondary way. 5 The standard treatment used with laminitis as well as in many other of the complications associated with Cushing's disease is the non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAID's) to relieve pain and decrease inflammation. In cases of laminitis very high doses may be used as the horses are in extreme pain. Other drugs that may be used in the laminitis cases to alter the circulation or reduce swelling, such as DMSO, nitroglycerine patches and isoxuprine or heparin. Since many of the horses have chronic infections, high doses or repeated courses of antibiotics may be used. Intestinal permeability and its relationship to laminitis Research has been done regularly on NSAID's effects and toxicity in the horse as well as in humans.33 One recent equine necropsy study showed inflamed small and large intestinal walls after 12 days of phenylbutazone administration.34 This study also showed the comparative toxicity of several NSAID's (phenylbutazone, flunixin, and ketoprofen). Phenylbutazone caused edema in the small intestine and erosions and ulcers in the large intestine. Phenylbutazone toxicity studies showed hypoprotenemia and suspected protein-losing enteropathies in a majority of horses in the studies.35-37 Gastric ulcers in horses are common and may be due in part to the use of phenylbutazone. Pollitt's recent work indicates involvement of a leaky basement membrane in the intestinal wall as part of the pathophysiology of carbohydrate overload laminitis.1 A leaky basement membrane allows the (Streptococcus bovis) bacterial exotoxin to cross into the bloodstream. This exotoxin is capable of essentially melting the basement membrane of the laminae in the foot.38 Much research has been done in human medicine concerning the involvement of the leaky intestinal tract basement membrane in the pathophysiology of many diseases.39, 40 In the leaky bowel the basement membrane allows large molecules to pass through the portal circulation into the liver and form immune complexes which are then distributed to the joints and other locations in the body.39 Bacteria and bacterial products are well known to leak through the basement membrane.40 It has been shown that a single dose of endotoxin increases intestinal permeability in humans.41 Human studies have linked "leaky bowel" to various diseases including arthritis, which is significant since NSAID's are commonly used to treat arthritis in both the human and animal populations.39 Many horses spend much of their lives receiving phenylbutazone on a daily basis for weeks, months and even years, leaving the intestinal tract basement membrane in poor shape. The implications of the research are that high doses of the NSAID's could be detrimental to the integrity of the intestinal wall in laminitis cases. Consequently, the use of NSAID's in treating laminitis should be questioned. Also, a potential cause of laminitis, especially chronic laminitis, may lie with the integrity of the gut wall. Preliminary results from a well-established human functional medicine testing laboratory support the hypothesis of poor intestinal function in some of the Cushing's and laminitis horses (Harman, unpublished data). Clinically, in these authors' experience the removal of the NSAID's is one of the most important aspects of the success of the holistic treatment. The horses' symptoms are usually worse for three to five days after removing the NSAID's, so they lie down more. That can be alarming to the owners and attending veterinarians, however, it is best for the horse, since they take the pressure off the feet and allow the antioxidants to work. When the horses feel better with natural medicine it is because they are better, not because the pain was masked. Repairing the gastro-intestinal tract The integrity of the gastro-intestinal system is vital in preventing formation and release of exotoxins into systemic circulation. The authors have adapted many of the treatments that have been used successfully in humans. The gastrointestinal tract is also responsible for the breakdown and assimilation of nutrients needed to maintain and restore health. The most important first step is to stabilize the intestinal wall and restore the beneficial flora. Antibiotic use leads to unbalanced intestinal flora that contributes to the leaky bowel syndrome.42, 43 Probiotics may restore the pH and gut flora to a healthier environment. Beneficial bacteria such as Enterococcus faecium, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. casei, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Streptococcus faecim are indigenous to the horse's digestive system. The bacteria help maintain proper pH levels in the system, 44, 45 manufacture vitamins such as biotin and digest fiber. Supplementation using a variety of equine probiotics should be considered. Glutamine is an amino acid that is a primary fuel for the enterocytes of the small intestine. Glutamine levels are affected by any decrease in feed intake as well as any stress placed on the intestine such as sepsis or endotoxemia.46 Glutamine has been shown to reduce bacterial translocation across the gut wall47 and should be considered in any horse that is not eating correctly, as well as any horse where intestinal wall integrity may be questionable. Doses range from 10 to 35 gm per day, depending on the size of the horse. Processed grains and hays may lose key ingredients during manufacturing since pellets and extruded feeds are made at high temperatures. In some cases horses have difficulty digesting processed feed, yet in these author's experience, when many horses are fed plain grains they gain weight and are healthier. Some horses digest their food better when digestive enzymes are added. The aphanizomenon flos-aquae strain of blue-green algae is high in chlorophyll and anti-oxidant nutrients such as beta-carotene. It also contains active digestive enzymes so it provides concentrated nutrition to help support healing without placing any additional stress on the digestive tract. Aloe vera is an herb that has shown some clinical efficacy in treating the side effects of the NSAIDs. Its antiinflammatory effects are possibly from its inhibitory action on the arachidonic acid pathway via cyclooxygenase.48 Slippery elm bark is another nutritional herb, which protects and aids in healing the intestinal wall. It has a mucilage effect that appears to sooth the intestinal wall, however, there is little research to support its use.49 Nutrition Nutritional support is critical in the laminitic horse and includes the basics of feed, water and hay as well as specific nutrients. The nutrients discussed here are ones these authors have found clinically useful. Feed Once the digestive system is supported, high quality nutrients should be provided. The nutritional requirements for horses with laminitis appear to be higher than normal horses. Horses with Cushing's-based laminitis need high fiber, low carbohydrate diets. Wheat bran can be added as a source of fiber taking care to keep the calcium phosphorus ratio correct in the overall diet. Blue-green algae can be added to the bran to provide amino acids and trace minerals. Grass or other lower protein hays can be given free choice. Some horses can tolerate an alfalfa/grass hay, especially if more protein is needed. Generally alfalfa should not be used alone and should not be fed to the very overweight horse. The feed should be low in sugar if the horse has signs of Cushing's syndrome with altered insulin levels or diabetes. Sweet feeds should be avoided. In humans increased insulin levels can begin in childhood.50 Cushing's in horses may begin during their younger years. Most of the prepared diets for foals and young growing horses are extremely high in sugar. The connection between feeding high sugar diets and Cushing's disease has not been proven in horses, but there is a strong connection being made in humans with high sugar diets and insulin resistance.51 When evaluating the feeding program, examine the treats being given. Many people feed treats high in sugar including large quantities of apples and carrots. Plain corn (about 25%), barley (about 35%) and oats (about 45%) make a simple, clean grain mixture without sugar. Some of these grains may not be available or useable in certain parts of the country depending on harvest situations. Some horses react poorly to eating oats; if that seems to be the case, barley and corn together are enough. Higher levels of protein (up to 14%) and calories may be needed in the horses with weight loss problems, but should not be fed to normal or overweight horses.52, 53 Cushing's horses that are normal weight or underweight often do well on the senior diets, which are higher in protein and fat. Many chronic laminitis horses lose weight due to the stress of walking in pain and actually need increased amounts of feed. Practitioners often restrict feed in all laminitic horses, however, some horses need extra calories to maintain normal physiologic functions. Increased calories can be given as fats (vegetable oils or rice bran) and are well digested by most horses. Increasing total calories with oils may be preferable to using high-protein feeds and hays. Antioxidants Coenzyme Q10 is useful in reversing free radical damage secondary to sepsis from an endotoxin overload. This is thought to occur with the coenzyme Q10 acting as an oxygen free radical scavenger, thus stabilizing mitochondrial membranes, and by inhibiting the arachidonic acid metabolic pathway and the formation of various prostaglandins.54 Coenzyme Q 10 clinically seems to be one of the best antioxidants for use in laminitis cases. Horses become less painful rapidly when Co Q 10 is used without concurrent NSAID's. The therapeutic dose is 300-600mg per day for the first week or two, then the dose can be decreased slowly to a maintenance of about 100 mg per day. Vitamin C is an excellent antioxidant that can regulate the phagocytic process in endotoxic shock, mainly by decreasing free radical production.55 Vitamin C is also a nutrient for collagen manufacture as well as offering some immune system support. Doses range from 3 to 8 gms per day. Horses tolerate these doses well with few cases of diarrhea or stomach irritation. Other antioxidant nutrients that may be useful are Vitamin E, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and dimethylglycine (DMG). These antioxidants are generally used by the authors in the more refractory cases. Minerals One of the most important aspects of any nutritional program for horses is the use of free choice minerals with the salt fed separately. Many laminitis horses will eat large quantities of minerals for extended periods of time indicating their need for minerals. A commercial salt-mineral block contains about 94% salt so horses that do not crave salt will not consume the amount of minerals they need. The authors have observed horses consuming large quantities of minerals when provided mineral supplementation with salt fed separately. There are several key minerals needed for glucose metabolism that help the Cushing's horses. Magnesium affects insulin secretion and its action in the cells. Magnesium also helps the cells be more flexible and permeable to insulin.56 Chromium helps make muscle more sensitive to insulin so glucose can be taken into the muscle cells more easily. Chromium is also related to elevated blood sugar and has been shown to be effective in reducing fasting blood sugar levels.57, 58 Vanadium or vandyl sulfate has actual insulin-like effects on glucose metabolism59 which helps transport glucose into the cells.60 MSM is a natural source of sulfur. Sulfur is important as it helps make up the disulfide bonds in the laminae. The disulphide bonds are an important part of the connects the hoof wall to the healthy lamina.61 Sulfur may be an important nutrient for these horses and can be fed free choice or in a supplement such as MSM. Vitamins It is important to supply high quality supplements to help these horses heal. Prepared foods cannot have all the vitamins needed by a sick animal. However, formulated supplements which contain low quality, synthetic vitamins, inorganic minerals, and fillers may actually cause the horse's system to become more out of balance. Food-source vitamin mineral supplements include: blue-green algae, kelp, apple cider vinegar, carrots, and oranges. Several companies manufacture additive-free supplements. Essential fatty acids Essential fatty acids (EFA's) are needed to help make the cell wall more sensitive to insulin.62, 63 Omega 3 fatty acids are especially deficient in human diets and may be deficient in many equine diets. Most of the high fat equine foods use animal fat that is high in saturated fats rather than vegetable oils. Flax and hemp oil provide Omega 3 fatty acids that are palatable to the equine, though fish oils may have an even better fatty acid profile.63 Other compounds that may be useful The authors have used several other forms of complementary medicine when treating Cushing's cases. Chinese medicine, both acupuncture and Chinese herbs, homeopathy and glandulars are used in many of the cases treated. The research does not support their use so the inclusion here is purely anecdotal, yet in these author's cases these modalities have proven useful. Management factors Cold therapy The use of cold baths to cool the foot has at times been advocated. In light of Pollitt's research cold should be used regularly in the first 48 hours, especially in known grain overload or toxic case situations.1 Hoof Care The damage to the hoof in laminitis cases can be kept to a minimum by following a few guidelines. 1: Do not use drugs to mask the pain. If the pain is masked, the horse will continue to walk on the damaged lamina and cause more damage. Natural antioxidants will allow healing without masking the pain. The best thing a horse with severe laminitis can do is lie down and take weight off the damaged feet. 2: Provide deep sand bedding if possible, or use Styrofoam taped to the bottom of the feet-- 2 inch thick blue builder's Styrofoam. Washed river sand will shift under the horse allowing him to stand in the most comfortable position. It will also shift under pressure points to keep pressure sores to a minimum. Horses with tight tendons will often stand with the toes buried in the sand and the heels elevated. The way the horse stands in sand is a good way to determine how to shoe him. 3: Keep the hooves soft and pliable. Horses with laminitis generally have swelling within the hoof capsule and a soft hoof will expand to relieve pressure. If the hoof gets too hard, a poultice should be applied overnight. Using a rasp to thin the hoof at the toe can also give relief. 4: Shorten the toe to ease breakover. A long toe will act like a lever and cause more tearing of the hoof lamina. The natural balance approach to trimming the foot in line with the coffin bone, then raising the heels and slowly lowering them to relieve the tendon pull with special shoes can be extremely beneficial. Natural balance trimming must be done correctly in order to work. If the farrier does not understand the principles, more damage can result. 5: Encourage abscesses to drain. Avoid treating abscesses with systemic antibiotics or anti-inflammatory drugs. Drugs may temporarily suppress the maturation of an abscess allowing it to spread deeper into the foot. Abscesses are natures way of debriding the dead tissue from the damaged laminae so it is important they are allowed to drain. Soaking in Epson salts or poulticing will encourage the abscess to mature and open to the outside of the hoof. Rasping the hoof wall thin at the toe will give the abscess a place to drain. 6: Avoid shoeing procedures when the feet are extremely sore. Horses with acute episodes have very sore feet, pulling shoes and hammering will cause extreme pain. If the toes are long, carefully remove the shoes and bed in deep sand. Toes can be rasped back more easily if the hoof has been softened with a poultice. Several pads are available which can be taped on to provide frog support or raise the heels. Environment Many horses are kept in high stress situations that contribute to adrenal stimulation and cortisol release. If it is possible to decrease environmental stress, the horse will benefit greatly. Many of these horses may be past their high-stress years, and the current owner may not be showing heavily or keeping the horse in the high stress environment, yet Cushing's disease is still a factor. These horses are experiencing the previous lifetime of stress, excessive drug use and poor nutrition. Cushing's is the result of many years and many factors. Pasture turn-out time is very important; however many horses cannot be on rich pasture without exacerbating their symptoms. Clients should be encouraged not to fertilize their fields or mow and manage them too carefully. Natural fertilization with trace minerals is a good practice, though if grass becomes too rich from good organic practices an overweight horse will result. A few weeds (herbs) are a good thing. For many horses a "fat pen" will need to be built, just a small area outside with minimal grass so they can be out in the sunshine and near their friends, but not have too much grass. Conclusion Prevention is still the best way to manage laminitis in horses, however, chronic laminitis cases can recover with a multi-faceted, long-term natural treatment plan. Treat each horse as an individual and seek quality practitioners to help you. Use as much whole food nutrition as possible, supplement with specific nutrients as needed, reduce stresses and vaccinations, and support a healthy digestive tract. References 1. Pollitt, C. Equine laminitis: A revised pathophysiology. Proceedings Am Assoc Eq Pract, 1999:45: 188-192. 2. Boujon CE, Bestetti GE, Meier HP et al. Equine pituitary adenoma, a functional and morphological study. J Comp Path. 1993;109: 163-178. 3. Millington WR, Dybal NO, Dawson R Jr, et al. Equine Cushing's disease: differential regulation of _ endorphin processing in tumors of the intermediate pituitary. Endocrinology. 1988;123: 1598-1604. 4. Dybal NO, Hargreaves KH, Madigan JE et al. Diagnostic testing for pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction in horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;204: 627-632. 5. Dybal, N. Pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (equine Cushing's-like disease). In: Robinson NE, ed. Current Therapy in Equine Medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997:499-503. 6. Orth DN, Holscher MA, Wilson MG et al. Equine Cushing's disease, plasma immunoreactive proopiolipomelanocortin peptide and cortisol levels basally and in response to diagnostic tests. Endocrinology. 1982;110: 1430-1441. 7. Greco, D and Stabenfeldt GH. Endocrinology. In Cunningham JG, ed. Textbook of Veterinary Physiology, Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997:385-403. 8. van der Kolk H. Diseases of the pituitary gland, including hyperadrenocorticism. In: Watson TDG ed. Metabolic and Endocrine Problems of the Horse, Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998: 41-59. 9. Kolk JH van der, Kalsbeek HC, Garderen E van et al. Equine pituitary neoplasia: a clinical report of 21 cases (1990-1992). Vet Rec. 1993;133: 594-597. 10. Hillyer MH, Taylor FGR, Mair TS, et al. Diagnosis of hyperadrenocorticism in the horse. Equine Vet Edu. 1992;4: 131-134. 11. Love S. Equine Cushing's disease. Br Vet J. 1993;149: 139-153. 12. Heinrichs M, Baumgartner W, and Capen CC. Immunocytochemical demonstration of propiomelanocortin-derived peptides in pituitary adenomas of the pars intermedia in horses. Vet Path. 1990;27: 419-425. 13. Sojka JE, Johndon MA and Bottoms GD. Serum tri-iodothyronine, total thyroxine, and free thyroxine concentrations in horses. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54: 52-55. 14. Beech J and Garcia M. Hormonal response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone in healthy horses and in horses with pituitary adenoma. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46: 1941-1943. 15. Xie H. Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine. Beijing Agricultural University Press. Beijing, China. 1994:255-287. 16. Maciocia, G. The Foundations of Chinese Medicine. Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY. 1989:253-254. 17. Garcia MC, and Beech J. Equine intravenous glucose tolerance test: glucose and insulin responses of health horses fed grain or hay and of horses with pituitary adenoma. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47: 570-572. 18. Auer DE, Wilson RG, Groenendijk S, et al. Glucose metabolism in a pony mare with a tumour of the pituitary gland pars intermedia. Aust Vet J. 1987;64: 379-382. 19. Allen JR, Barbee DD and Crisman MV. Diagnosis of equine pituitary tumors by computed tomography, part 1. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 1988;10: 1103-1106. 20. Baker JR and Ritchie HE. Diabetes mellitus in the horse: a case report and review of the literature. Eq Vet J. 1974;6:7-11. 21. Loeb WF, Capen CC and Johnson LE. Adenomas of the pars intermedia associated with hyperglycemia and glycosuria in two horses. Cornell Vet. 1966;56: 623-626 22. Field JR and Wolf C. Cushing's syndrome in a horse. Eq Vet J. 1988;20: 301-304. 23. Reed, SM. Pituitary adenomas: equine Cushing's disease. In: Reed SM and Bayly WM, eds. Equine Internal Medicine, Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1998: 912-915. 24. Zavaroni I, Bonini L, Fantuzzi M, et al. Hyperinsulinemia, obesity and syndrome X. J Int Med. 1994;235: 51-56. 25. Bogardus C, Lillioja D, Mott M, et al. Relationship between degree of obesity and in vivo insulin action in man. Am J Physiol. 1985;248 (Endocrinol Metab II):E286-E291. 26. Reaven, GM. Pathophysiology of insulin resistance in human disease. Phys Rev. 1995;75(3): 473-485. 27. Reaven, GM. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37: 1495-1507. 28. Adamo M, LeRoith D, Simon J. Effect of altered nutritional states on insulin receptors. Ann Rev Nutr. 1988;149-166. 29. Cline GW, Peterson KF, Krssak M, et al. Impaired glucose transport as a cause of decreased insulinstimulated muscle glycogen synthesis in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1999;341: 240-246. 30. Neel JV. The "thrifty genotype" in 1998. Nutr Rev. 1999;57(5): S2-S9. 31. Coffman JR, Colles CM. Insulin tolerance in laminitic ponies. Can J Comp Med. 1983;47:347-351. 32. Jeffcott LB, Field JR, McLean JG et al. Glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in ponies and standardbred horses. Eq Vet J. 1986;18: 97-101. 33. Bjarnason I, Williams, et al. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prostaglandins on the permeability of the human small intestine. Gut. 1986;27(11):1292-1297 34. MacAllister CG, Morgan SJ et al. Comparison of adverse effects of phenylbutazone, flunixen meglumine, and ketoprofen in horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993;1:202 (1):71-77. 35. Lees P, Creed RF et al. Biochemical and hematological effects of phenylbutazone in horses. Equine Veterinary Journal. 15 (2):158-167, 1983. 36. Snow DH, Bogan JA et al. Phenylbutazone toxicity in ponies. Vet Rec. 1979;14:105(2):26-30. 37. Snow DH, Douglas TA, et al. Phenylbutazone toxicosis in equidae: a biochemical and pathological study. Am J Vet Res. 1981;42(10): 1754-1759. 38. Pollitt CC, and Daradka M. Equine laminitis basement membrane pathology: loss of type IV collagen, type VII collagen and laminin immunostaining. Equine Hoof Equ Vet J Suppl. 1998;27: 139-144. 39. Inman RD. Antigens, the gastrointestinal tract and arthritis. Rheum Dise Clin N Am. 1991;17(2):309321. 40. Wells CL, Jechoreck RP et al. Relative contributions of host and microbial factors in bacterial translocation. Arch Surg, 1991;126:247-252. 41. O'Dwyer ST, Michie HR, et al. A single dose of endotoxin increases intestinal permeability in healthy humans. Arch Surg, 1988;123(12): 1459-1464,. 42. Darlington, LG. Dietary therapy for arthritis. Nut Rheum Dis/Rheum Dis Clin N Am, 1991;17(2):273285. 43. Schmidt, MA, Smith, LH, & Sehnert, KW. Beyond antibiotics. North Atlantic Books, Berkley, CA. 1993. 44. Clarke LL. Feeding and digestive problems in horses. Vet Clin N Amer Eq Prac. 1990;6(2):433-450. 45. Moore JN, Garner HE, Berg JN, et al. Intracecal endotoxin and lactate during the onset of equine laminitis: A preliminary report. Am J Vet Res 1979;40: 722-723. 46. 4Souba WW, Herskowitz K, et al. The effects of sepsis and endotoxemia on gut glutamine metabolism. An Surg. 1990;211(5): 543-549. 47. Souba WW, Klimberg VS, et al. Oral glutamine reduces bacterial translocation following abdominal radiation. J Surg Res. 1990;48(1): 1-5. 48. Vazquez B, Avila G, Segura D, Escalante B. Antiinflammatory activity of extracts from Aloe vera gel. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;55(1): 69-75. 49. Physicians Desk Reference for Herbal Medicines. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company. 1999:1196. 50. Barnard R, Ugianskis E, Martin D, et al. Role of diet and exercise in the management of hyperinsulinemia and associated atherosclerotic risk factors. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69: 440-444. 51. Garg A, Bantle H, Henry R, et al. Effects of varying carbohydrate content of diet in patients with noninsulin-dependant diabetes mellitus, JAMA. 199;271: 1421-1428. 52. Glade MJ, et al. Dietary protein in excess of requirements inhibits renal calcium and phosphorus in young horses. Nut Res Intern. 1985;31: 649-660. 53. Miller-Graber PA, Lawrence LM, Foreman JH, et al. Dietary protein level and energy metabolism during treadmill exercise in horses. J Nutr 1991;121: 1462. 54. Lelli JL, Drongowski RA, Gastman B, et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 on the mediator cascade of sepsis. Circ Shock. 1993;39(3): 178-87. 55. Victor VV, Guayerbas N, Puerto M, et al. Ascorbic acid modulates in vitro the function of macrophages from mice with endotoxic shock. Immunopharm. 2000;46(1): 89-101. 56. Paolisso G, Sgambato S, Gambardella A, et al. Daily magnesium supplements improve glucose handling in elderly subjects. Am J Clin Nut. 1992;55: 1161-1167. 57. Linday LA. Trivalent chromium and the diabetes prevention program. Med Hyp. 1997;49:47-49. 58. Evans GW, Bowman TD. Chromium picolinate increases membrane fluidity and rate of insulin internalization. J Inorg Bio. 1992;46:243-250. 59. French RJ, Jones PJ. Role of vanadium in nutrition: metabolism, essentiality and dietary considerations. Life Sci. 1992;52:339-346. 60. Schechter LI, Meyerovitch, et al. Insulin-like actions of vanadate are mediated in an insulin-receptorindependent manner via non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases and protein phosphotyrosine phosphates. Mol Cell Biochem. 1995;153(1-2): 39-47. 61. Grosenbaugh DA, Hood DM. Keratin and associated proteins of the equine hoof wall. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53(10): 1859-63. 62. McCarty MF. Complementary measures for promoting insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle. Med Hyp. 1998;51:451-464. 63. Gerbie A, Maixent JM, Ansalki JL, et al. Fish oil supplementation prevents diabetes-induced nerve conduction velocity and neuroanatomical changes in rats. J Nutr. 1999;129: 207-213. Table 1 hirsutism not shed out in the summer hyperhydrosis refractory laminitis winter laminitis weight problems (over-or underweight). sluggish thyroid glands insulin resistance thyroid dysfunction muscle soreness diabetes polyuria/polydipsia (Pu/Pd) collagen breakdown poor hair coat. frequent infections of the skin or other organs colic poor teeth < multiple dental abnormalities lowered immunity to intestinal parasites altered intestinal function laboratory tests decreased intestinal wall integrity. infertility muscle wasting.