Testing Hypothesis - Winona State University

advertisement

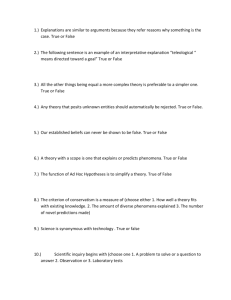

Biology 425 - Animal Behavior TESTING HYPOTHESES IN BEHAVIORAL STUDY Most of the interesting problems in behavior and life history strategies involve generating and testing hypotheses about the functions of observed behaviors. The goal always is to identify the best (most predictive) hypothesis, and eliminate less useful hypotheses. There are three major approaches to testing hypotheses; each amounts to supporting in the end what remains as the most likely hypothesis. (As Sherlock Holmes once pointed out, when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however unlikely, must be the correct answer). The trick, of course, it to be absolutely scrupulous, and make certain your tests are appropriate. The three procedures differ considerably in their effectiveness, and are listed here from least to most effective. 1. Generate your hypothesis, and locate data which agree with it. This is a very weak, but common, approach. The major weaknesses of this approach are that: (1) the data may also support other, unidentified hypothesis; and (2) no direct effort is being made to identify the weakest part of the hypothesis considered. These are the major weaknesses, for example, of Gordon Orians’ 1969 paper on mating systems (Amer. Nat. 103:589-603), and much of the literature (particularly the early papers) on foraging strategies. Once the hypotheses are generated, only supporting data are sought. Please note that I am not arguing that supporting data are insignificant. In some cases it may be truly difficult to generate testable hypothesis, and an author may make a deliberate decision to accumulate all possible data and see where the strength of the data lie. Nonetheless, this is generally a very weak method of testing hypotheses. ` 2. List all alternative hypothesis, and seek to support them, eventually choosing the one that seems best supported. Hoogland and Sherman, for example, did this is in their paper on the advantages and disadvantages of bank swallow coloniality (1976, Ecological Monograph 46:3358). This method has certain weaknesses and has been dismissed by many philosophers of science, including some relatively biological ones such as Ghiselin (1969, The Triumph of the Darwinian Method. University of California Press, Berkely)). First, it leads to the impression that all reasonable hypothesis have been considered -- when in fact it may be true that this end is never accomplished. Second, it leads to the construction of “straw-men” either deliberately or unconsciously, and to a less than rigorous test because of this. And indeed almost by definition this approach amounts to support of one’s consciously or unconsciously favored hypothesis. Third, as with the first method, it fails to focus on the most likely hypothesis and specifically explore its weaknesses. Finally, it may be a tedious method of locating the best explanation for a given phenomenon, because it fails to capitalize on what is already known about the relative merits of existing hypotheses. Imagine, if you will, the case in which you have generated only a single hypothesis: presumably, all you cold do then is to dream up alternatives, however weak, against which to test it. Nonetheless, when this approach is well used (and I think Hoogland and Sherman have used it well) considerable progress can be made in testing hypotheses. 3. The strongest approach to hypothesis testing is to seek explicitly to falsify the hypothesis -- that is, to specify the observations which would without questions show this hypothesis to be false. This method is the most widely used and respected method in scientific endeavors. It is commonly called the Popperian method (after Popper, 1968. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Hutchinson), but Darwin employed it explicitly and repeatedly. Darwin, himself, (1859:228 in the Origin of Species) provided the critical test for natural selection: “If it could be proved that any part of the structure of any one species had been formed for the exclusive good of another species, it would annihilate my theory, for such could have not been produced by natural selection.” Later, Alexander (see review in Alexander’s 1979 book, Darwinism and Human Affairs, Washington University Press) expanded this test to include all behavioral traits as well as morphological ones, and specified most clearly the individual level of selection. The chief virtues of the falsification approach to hypothesis testing are that it seeks the weakest aspect of the hypothesis and exploits them to the fullest; and it does not require the assumption that all alternative hypotheses have been erected and tested. In employing this method, we seek the most easily conducted falsifying exercises -- above all, those observations or experiments which are most likely to prove the hypothesis false from the evidence available about them. In this course, you will be required to generate hypothesis and to test them, or to specify what observations or experiments would test your hypotheses. You will learn to distinguish among these approaches to verify or test hypotheses, and you will be urged to use wherever possible the falsification approach.