book extract: defiant images

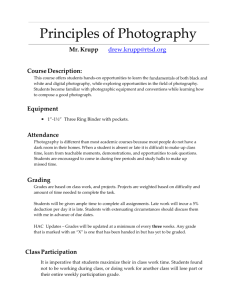

advertisement

Defiant images. Photography and Apartheid South Africa Darren Newbury. Unisa Press Format 193 x 250 mm (Laminated softcover) Pages 356 Published November 2009 ISBN 13 978-1-86888-523-7 Unisa Press Item no 8137 SA price: R215.00 (VAT incl) Rest of the world: Africa: R228.60 (Airmail incl) USA: Contact ISBS: http://www.isbs.com/ Europe: Contact Eurospan: http://www.eurospanbookstore.com/ Subject: South Africa; photography; social documentary; politics; apartheid “This book is much more than just a discourse on photography in the land of apartheid. And it goes well beyond sophisticated debate on the artistic merits of images. While keeping the lens trained on the evolution of photography it plunges the reader into a sharp and evocative socio-cultural history of a country in deep conflict.” – Albie Sachs Photography is often believed to 'witness' history or 'reflect' society, but such perspectives fail to account for the complex ways in which photographs get made and seen, and the variety of motivations and social and political factors that shape the vision of the world that photographs provide. Defiant Images develops a critical historical method for engaging with photographs of South Africa during the apartheid period. The author looks closely at the photographs in their original contexts and their relationship to the politics of the time, listens to the voices of the photographers to try and understand how they viewed the work they were doing, and examines the place of photography in a postapartheid era. Based on interviews with photographers, editors and curators, and through the analysis of photographs held in collections and displayed in museums, Defiant Images addresses the significance of photography in South Africa during the second half of the twentieth century Contents Foreword vii Acknowledgements xi List of figures xv Introduction 1 1 An African Pageant: Between Native Studies and Social Documentary 15 2 ‘A Fine Thing’: The African Drum 3 ‘Johannesburg Lunch-hour’: Photographic Humanism and the Social Vision of Drum 113 4 An ‘Unalterable Blackness’: Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage 173 5 An Aesthetic of Fists and Flags: Struggle Photography 219 6 ‘Lest We Forget’: Photography and the Presentation of History in the Post-apartheid Museum 271 81 Epilogue 317 Select Bibliography 323 Introduction 1 Index 332 About the author Darren Newbury is Professor of Photography at Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, Birmingham City University. He studied photography and cultural studies at undergraduate and postgraduate level, and completed his PhD in 1995. His research interests are in photography, photographic education and visual research methods. He has published in journals including: Disability and Society; Journal of Art and Design Education; Journalism Studies, Visual Anthropology; British Journal of Sociology of Education; The Curriculum Journal; Visual Anthropology Review, Visual Communication, Visual Culture in Britain, Visual Studies. He is also current editor of the international journal Visual Studies (since 2003). His book on photography in apartheid South Africa has involved fieldwork, interviews and archival research in South Africa, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States, and has been supported by two awards from the Arts and Humanities Research Council. He has served as an AHRC Peer Review College member, Postgraduate Panel member and convener, and Postgraduate Committee member. He has also been involved in the development of doctoral education and training in art and design since the mid 1990s. Other recent and forthcoming publications Picturing an ‘ordinary atrocity’: photographs of the Sharpeville Massacre, 21 March, 1960. In Picturing Atrocity: Reading Photographs in Crisis. Edited by Geoffrey Batchen, Mick Gidley, Nancy Miller and Jay Prosser. Reaktion Books, London. Forthcoming 2010. Living historically through photographs in post-apartheid South Africa: reflections on Kliptown Museum, Soweto. In preparation for: Curating Difficult Knowledge. Publication planned for 2010. Image, theory, practice: reflections on the past, present and future of photographic education. Photographies Vol.2 No.2, 2009, pp.117-24. ‘Lest we forget’: photography and the presentation of history at the Apartheid Museum, Gold Reef City and the Hector Pieterson Museum, Soweto. Visual Communication Vol.4 No.3, 2005, pp.259295. Documentary practices and working-class culture: an interview with Murray Martin (Amber Films and Side Photographic Gallery). Visual Studies Vol.17 No.2, 2002, pp.113-128. Telling stories about photography: the language and imagery of class in the work of Humphrey Spender and Paul Reas. Visual Culture in Britain Vol.2 No.2, 2001, pp.69-88. Reprinted in Peter Hamilton (ed.), Visual Research Methods, Volume 2, London: Sage, 2006, pp.295-320. Contact the author Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, Birmingham City University, Gosta Green, Birmingham, B4 7DX, United Kingdom. Email: darren.newbury@bcu.ac.uk BOOK EXTRACT: DEFIANT IMAGES Introduction At a seminar on ‘Photography, Politics and Ethics’, in Johannesburg, 2004, 1 Susan Sontag talked about being struck, on what was her first visit to South Africa, by the strong moral and ethical Introduction 2 dimension within South African photography, and the attention given to the politics of photographic representation. It was an observation that resonated with my own experience, like Sontag an outsider, when visiting the country for the first time just two years previously. The power of photography as a means of documenting reality or showing the truth about society, 2 which was exploited most compellingly during the apartheid period, remained central to debates about the medium ten years after the first democratic elections. Unlike Europe and the United States of America (US), where during the 1970s and 1980s documentary photography had been ‘problematised almost to the point of paralysis’,3 in South Africa there persisted a strong sense of its value as a means of commenting on issues of social and political importance within a visual public sphere. At the same time, the charge of naïve and uncritical humanism that had been levelled at documentary photography elsewhere did not apply.4 There could hardly be a society in which the politics of making and showing images was more apparent. The debates about representation and photographic truth were sophisticated and the photographers articulate. I was left with the sense that South African documentary could not be fitted easily into histories of photography written, as they largely have been, from the point of view of Europe and the US. My desire to understand the complex relationship between photography and the social and political context as it had developed during the apartheid period brought me back to South Africa. This book is the result. Recent years have seen a substantial critical and curatorial interest in African photography from both the colonial and postcolonial periods. A series of major international exhibitions from the early 1990s onwards launched African photography on the world stage and attracted a great deal of critical attention, as well as generating an increase in the popularity of African photography amongst an international gallery visiting public.5 But the position of South African documentary photojournalism in this emerging discourse on ‘African’ photography is not straightforward. Whilst South Africa is well represented in surveys of twentieth century photography, such as Revue Noire’s hugely significant Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography,6 theoretical efforts to define an African photographic aesthetic have tended to be more exclusive in their approach. Two exhibitions have been particularly influential, establishing a lineage for African photography and framing its interpretation within an international cultural arena: the 1996 Guggenheim exhibition In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present (curated by Clare Bell, Okwui Enwezor, Danielle Tilkin and Octavio Zaya); and ten years later, Snap Judgements: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography (curated by Enwezor and exhibited at the International Center of Photography in New York). Accompanying catalogue essays by Enwezor situate African photography within a postcolonial theoretical framework. In the first of these, Enwezor offers a sensitive and sympathetic reading of the photojournalism in Drum,7 referring to Jürgen Schadeberg’s ‘sharp clarity and great compositional skill’, Peter Magubane’s ‘intimate humanism’, and the insights the magazine provides into the popular culture and everyday life of 1950s South Africa and the ‘disparate African subjectivities that existed apart from the constructs of the colonial enterprise’. 8 Yet, the argument is distorted by the need to discern an essentially African style or quality. The photographers are described as ‘defying the conventions of traditional documentary’9 when it would be more realistic to argue that they were in the Introduction 3 process of establishing these conventions in a South African setting; the documentary paradigm in South Africa, it seems, is compromised by its close association with photographic practices imported from Europe and the US. And documentary’s significance is closely tied to historical events – ‘an eyewitness to those events defining the course of South Africa’s political and social landscape’ 10 – setting limits on its ability to transcend the context of apartheid. Despite concluding with the idea that this work ‘opens up routes to many discourses’, 11 Enwezor draws no line forward from the work of Drum in his later writings. The documentary tradition, which provided a ‘tent pole of mid-century African modernism’ in the earlier exhibition,12 subsequently disappears from view. For those African photographers considered to be working in a documentary photojournalist tradition, the later rhetoric emphasises their escape from, rather than their development of, this tradition, which appears only as a force for ‘Afro-pessimism’.13 Documentary photography is qualified as either ‘straight’ or ‘Western’ and where it is discussed at all, seems to provide the antithesis of a genuinely African photography. African agency is only possible, it seems, by marking a distinction from the documentary tradition, never within it. South African documentary photography and photojournalism are relegated to a footnote in history and appear bounded both historically and geographically by apartheid: ‘Because of the depredations of apartheid, the documentary style became the dominant photographic genre in South Africa. Photography was consistently used in the service of news reportage and in the ideological struggle between the apartheid state and its opponents’.14 In/Sight appears in retrospect to have been an obituary for the documentary tradition in Africa.15 Postcolonial writers on African photography have looked elsewhere to ‘rediscover’ African agency. 16 Central to the argument is the priority given to the West African portrait photography produced during the 1940s and 1950s, specifically the paradigm examples of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé from Mali, who in a series of stunning images dramatised the ‘burgeoning and self-conscious modernity’17 of an urban African population on the cusp of decolonisation. The theoretical and historical weight these images are asked to carry is their embodiment of the distinction between colonial photography and postcolonial African photography: ‘Most modern African portrait photography constitutes an attempt at straightforward depiction of a social self, more specifically, the African self. In these portraits, beginning in the late nineteenth century, the point of view is always direct and always centred on the subject, unlike colonial photography, which usually imaged the African subject as a specimen of some exotic investigation’. 18 In short, Enwezor argues, ‘to look at Keïta’s portraits of the urban inhabitants of Bamako is to witness the near disappearance of colonial subjectivity’.19 Olu Oguibe, writing in the catalogue for Flash Afrique (2001), makes essentially the same point when he states that, ‘the ritual of self-imagining would become the singular, most important sustaining framework for photography in Africa’.20 For both writers vernacular portraiture is synonymous with African agency.21 Introduction 4 The African portrait tradition is clearly important, but its dominance within postcolonial photographic theory threatens to obscure or devalue a broader understanding of photography in Africa, and particularly South Africa where documentary photojournalism has been, and remains, so important. The discovery of agency in vernacular modernist photographic practices has been the leitmotif of postcolonial photographic theory. However, in combination with a search for the ‘authentically African’, it has served to position the documentary tradition, with its inevitable association with the West, outside of the frame of recent scholarship.22 It is this critical lacuna that I intend to address in this book. Departing from recent writing about photography on the continent of Africa, I want to reconsider the documentary tradition in South Africa, not as an authentically African tradition, whatever that may mean, but rather as a complex set of photographic ideas and practices that were self-consciously both modern and international, and yet at the same time thoroughly South African. 23 At the centre of this book is the ambition to understand how and why documentary photography developed in the way that it did within apartheid South Africa. The extent to which the fact of apartheid shaped the possibilities for photographic practice during this period renders any attempt to construct a history of South African photography divorced from this context beside the point. William Beinart’s argument that ‘apartheid became so dominant a feature of life over the next forty years [from 1948] that it must be intrinsic to a description and understanding of this period’ applies equally to photography and visual culture in South Africa as it does to society and politics.24 The narrow election victory of D. F. Malan’s National Party (NP) in May 1948 represented the beginning of the apartheid period. Of course South Africa was far from an equal society before 1948. A more thorough historical account would consider exploitation and oppression during the earlier colonial periods, and in the Union of South Africa established in 1910, not least the Native Land Act (1913), which consolidated a deeply iniquitous division of land ownership to the benefit of the white settler population. Nevertheless, the Nationalists were ‘more determined and more confident of state power than most of their predecessors’;25 they established ‘a more intense system’ of segregation and ‘enshrined racial distinctions at the heart of [their] legislative programme’;26 ‘half a century of oppression and confusion began’.27 The NP quickly enacted the key pieces of legislation that would form the architecture of the apartheid state. The Population Registration Act (1950) and the Group Areas Act (1950) were centrepieces in this programme. The former put in place the notorious ‘pass laws’, racial classification became compulsory, and documents stating an individual’s racial group were issued. The Race Classification Board was set up to adjudicate disputes. The Group Areas Act (1950) along with the Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act (1951) facilitated the work of apartheid planners in creating separate racial zones to control the movement and residence of the population. This led to the forced removal of black, Indian and coloured people from city centres, and the redesignation of areas as ‘white’.28 Residents of Sophiatown, the Johannesburg suburb immortalised in the writing and photography of Drum as the vibrant centre of African intellectual and cultural life, were subject to forced removal; the area became a white suburb renamed Triomf. The population of District Six, a central area of Cape Town and now the subject of an important post-apartheid museum, was Introduction 5 similarly displaced, although in this case the area remained largely unoccupied more than ten years after the first democratic elections. The Bantu Education Act (1953) saw central state control of African education. The mission schools, with their ‘emphasis on English and dangerous liberal ideas’29 were replaced with a poorly funded technical education, using African vernacular languages at the lower levels with a mix of Afrikaans and English at the higher levels. The underlying aim of the system was ‘retribalization’ and the production of ‘a cheap but not entirely illiterate labour force’. 30 The government used the Suppression of Communism Act (1950) widely to restrict political organisation on the part of Africans and to disrupt and ban the activities of the African National Congress (ANC), the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) as well as the South African Communist Party (SACP). Apartheid legislation also reached into the personal lives of South Africans with the Mixed Marriages Act (1949) and Immorality Act (1950) making sex and marriage between individuals of different racial groups illegal, and expressing the fear of miscegenation and the symbolic threat it presented to the ideology of purity that informed the Afrikaner state. And in acts such as the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act (1953) ‘petty apartheid’ legislation created some of the most obvious and visible signs of apartheid in the daily lives of the South African population; signs which would become ‘a favoured target of opposition cartoonists and foreign photographers’,31 and provided a visual shorthand for apartheid. To set against the implementation of increasingly oppressive legislation, it is possible to draw a picture of resistance: the ANC Defiance Campaign of the early 1950s, a collective, non-violent response to the passing of unjust laws; the adoption of the Freedom Charter by the Congress of the People at a mass meeting in Johannesburg in 1955; the anti-pass campaigns, one of which, supported by the PAC, in March 1960 led to the Sharpeville Massacre, and the increasingly brutal oppression of black political activity that followed; the setting up of the armed wing of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), under Nelson Mandela’s leadership and the subsequent exile and imprisonment of many in the leadership of both the ANC and PAC; the Black Consciousness Movement; and the Soweto Uprising against the increasing use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in schools. The photography that emerged from South Africa during this period was interwoven with these events and this history. It cannot be defined solely in terms of the political context, but neither can it be separated from it. The photographers somehow had to position themselves in relation to the central fact of apartheid. Photography provided a means of recording some of the key events of the apartheid period – the Defiance Campaign, the Treason Trial, the Sharpeville Massacre, the Soweto Uprising – all of which provided material for photographic work and that now forms the archive on which many contemporary museums displays draw. The representation of black politics was relatively new in the 1950s: when Jürgen Schadeberg photographed at the ANC conference in Bloemfontein in December 1951, he was the only photojournalist to do so. 32 Equally important are the ways in which the practice of photography interacted with the apartheid system. Many of the stories that the photographers recount from this period involve negotiating the terrain of apartheid. The encounter Schadeberg recalled of being arrested under the Immorality Act whilst photographing Dolly Rathebe for the cover of Drum dramatised one instance of the constant negotiation with the social and political environment Introduction 6 that being a photographer demanded. Other photographers tell stories of cameras concealed in milk cartons or loaves of bread. At times photography served a more active stance, becoming a means of resistance, a site of struggle. It was the black photographer Ernest Cole’s manipulation of the racial classification system in order to get himself reclassified as ‘coloured’ that facilitated his classic photographic indictment of apartheid, House of Bondage;33 and the pursuit of this project that made his departure into exile inevitable. These many acts of defiance were part of the culture of South African photography. But photography was about more than the politics of apartheid. Whilst political events provided the key landmarks of the period, South African society also experienced profound social change. The decades prior to the advent of apartheid saw a rapidly growing permanent urban black population, establishing itself alongside older patterns of migrant labour. Between 1936 and 1948 the black population of Johannesburg nearly doubled in size.34 This new environment provided a rich mix of subject matter for photographers. Urban poverty, the growth of informal squatter settlements, and the work of social reformers all came under the scrutiny of the camera; so too did the black culture of the city, the township streets, the illegal brewing of alcohol, gang culture and the various musicians, politicians and sports figures who came to prominence. The early 1950s were a moment of intense black cultural creativity, centred particularly on Johannesburg, and often likened to the Harlem Renaissance. In this fertile environment, photography provided an eloquent medium with which to portray the social and cultural landscape of urban black South Africa. Although, the first attempts to document urban black existence were made by white photographers and sprung from a liberal-reformist ethos, it was to be the social and cultural aspirations of middle and working class urban blacks forced to live cheek by jowl in inner-city locations, such as Sophiatown, that did most to shape the black photography which emerged in the early apartheid years. The combination of urban working class cultural resistance and middle-class achievement gave a distinctive quality to Drum and its photography. It is impossible to describe the photography of this period without reference to this self-confident modern urban sensibility. The apartheid system was undoubtedly oppressive and often brutal; it set the context in which photographers worked, shaped much of the subject matter which they photographed, and often restricted the images that could be shown. But its control was far from total. Despite the economic injustice and political oppression of the apartheid period, black South Africa remained open to global cultural influences;35 this was especially true during the early apartheid years, before Sharpeville. Photography was a significant channel through which these influences arrived in South Africa; directly in some cases, in the form of photographers and editors from Europe, but also indirectly as South African photographers absorbed the visual culture of Europe and the US. Illustrated magazines, such as Life and Picture Post, were familiar to many of the photographers, and Drum was shaped in their image. It was also to the wider world that photographers looked for an audience for their work. It was not by accident that Leon Levson’s major exhibition on the subject of black South Africa travelled first to London; the journey had long been familiar to those petitioning the colonial power on behalf of black Introduction 7 South Africans. Nor is it surprising that it was in New York, London and Paris, rather than Johannesburg, that Cole found support for his book House of Bondage. Whilst the style of documentary photography that emerged during the apartheid years has its own distinctive characteristics, it can only be properly understood as part of an international photographic scene. From the beginning, South African photography existed within a complex network of international social, political and cultural relations. The approach I have developed in order to do justice to the subject has entailed a number of methodological commitments. Rather than treating the images as speaking for themselves, in either an ideological or aesthetic sense, I have sought to reconstruct the context from which they emerged. Through close attention to primary sources, I have attempted to trace the flow of ideas and images across countries and continents. In some cases this has involved literally tracing an often fugitive trail of evidence across the world, as well as within South Africa itself. In the case of Cole, for example, this led simultaneously inward to the township of Mamelodi where he lived in the 1960s, and outward to private and public collections in New York, London, Gothenburg and Amsterdam. I have engaged predominantly with photographs made for dissemination in the public sphere, both within South Africa and increasingly, towards the later years of apartheid, circulating internationally. Some of the photographs have become familiar points of reference, for example, as icons of resistance or as symbols of the depredations of the apartheid period. One of my primary sources of evidence, therefore, has been the images as they were published or shown. Many of the photographs have complex biographies, and I have attempted to follow their transition from first publication, for example, as photo-essays in Drum, into archival collections, exhibitions and museum displays in the post-apartheid era. I am concerned not so much with the single image, but the photo-essay, exhibition or body of work; interrogating each for the intentions of the photographers or editors and their possible meanings for their audience. I have studied the visual repertoires of photographic humanism and struggle photography, and the compelling descriptions of South African society they have provided. Wherever possible, I have paid close attention to the photographers themselves; what it was that they felt they were doing and how they perceived the meaning of their work. The theme of photographic creativity runs through the book. Photographers do not merely record, but rather construct an image of society. I have therefore conducted interviews or exchanged correspondence with many of the photographers discussed, as well as others who knew or worked with them. I hope the path I have taken avoids the many pitfalls of naïve oral history – I do not consider photographers the final arbiters on the meaning of their images – whilst at the same time keeping in mind that photographs are made by photographers, and without them there would be no visual record to inspect. The book is organised into six chapters. Although they are presented chronologically, I do not pretend to offer a comprehensive survey of South African photography during the apartheid period. Instead, my approach has been to discuss specific publications, organisations and photographers selectively. Introduction 8 The material I have chosen conforms to three criteria. First, all of the examples have shaped the use of photography as a creative visual medium. In other words, their significance is cultural as well as social or political. Second, they have evolved not simply against the backdrop of apartheid, but also in an international context; they cannot be understood apart from cultural exchanges between South Africa and the rest of the world. Third, they have contributed to a public visual discourse about South African society at critical points in its history. Specifically, I have chosen to focus on bodies of photographic work that stood more or less self-consciously in opposition to apartheid; they are examples of photography against apartheid. Whilst there is a convincing argument to be made that since the 1940s the leading edge of photographic practice in South Africa has been aligned with opposition to apartheid, readers should be aware that my selection of material is deliberate. There are of course omissions. I have not discussed, except in passing, the role of the white illustrated press. Nor have I paid much attention to vernacular photographic practices, which in their own way resisted or provided refuge from the oppression of the apartheid state. I have focused predominantly on the city, most often Johannesburg, and the townships, especially in the early years of apartheid. Quite simply this is where much of the work took place. But there are no doubt other histories of photography in South Africa during this period that could and should be written. Although the NP did not come to power until 1948, I have taken the immediate post-war years as my starting point (Chapter One). Apart from the fact that racial segregation itself has a long history, there are two reasons for doing so. It was during this period that photography began to develop selfconsciously as a means of commenting on South African society. The Second World War had propelled photographers such as Constance Stuart Larrabee into the public eye and the growth of the illustrated press provided a locus for the production and dissemination of photographic essays. Against a backdrop of rapid urbanisation, there emerged a social documentary photographic repertoire for the description of urban black African society to sit alongside the dominant paradigm of ‘native studies’, which until then had accounted for most photographs of black South Africans. The photographers were exclusively white and their politics predominantly liberal and paternalist. However, although somewhat hesitant and equivocal, in this period the first uses of photography as a means of opposition to the policies of the South African government can be seen. Tracing the different trajectories of Stuart Larrabee and Levson, both of whom were influenced by the growing status of photography as an art form and sought international audiences for their work, I hope to offer an insight into the articulation of photography, society and politics in post-war and early apartheid South Africa. If it proved to be a false dawn for a critical documentary tradition, this period nevertheless represented an important moment in the history of South African photography. Drum has a somewhat mythical status in the history of South African photography; and from the mid1980s onwards there has been a substantial re-publication in book form of many of the images from its first and most significant period (1951--1965), along with first-hand accounts by a number of its photographers and editors. However, there has yet to be a thorough critical and historical evaluation of this work. Drum photography has become synonymous with urban black South Africa in the 1950s. Introduction 9 Although in its first incarnation it drew on a somewhat limited repertoire for the visual depiction of black life, before long it gave rise to a new photography quite unlike anything South Africa had seen before. Looking first at its launch as The African Drum (Chapter Two) and the shape it subsequently took as it sought to appeal to an urban black readership (Chapter Three), I follow the development of Drum photography during a period of remarkable creative intensity. On one level, the documentary photography associated with Drum can be viewed as a cultural import from Europe and the US. Drum was one of the main publications providing a vehicle for the expression of an international humanist style and philosophy of photography in South African visual culture. However, I hope to demonstrate why this explanation is too simple. Drum was crucial to the development of black photojournalism in South Africa, providing a training ground, and connecting photographers such as Peter Magubane, Bob Gosani and Alf Kumalo to the international world of photojournalism. If the Drum era was distinguished by a sense of optimism and creative possibility, then the Sharpeville Massacre in March 1960 brought it to an abrupt end, ushering in an increasingly hostile climate for photographers. The 1960s were a difficult time for photography. By the end of the decade opportunities for publication were severely restricted and photographers found themselves increasingly subject to restrictions, state violence and oppression. Amongst them was Ernest Cole whose life and work is symbolic of the fate of humanist documentary photography in this bleak period in South African history. Although he worked for a brief while at Drum, his most significant work was completed alone and had to be smuggled out of the country before it could be seen. In 1966 he went into exile in the US to publish House of Bondage, a damning photographic critique of apartheid, which was both more comprehensive and systematic than any of the work that had been published previously. The book was banned in South Africa, but despite its scarcity became a key point of reference for subsequent anti-apartheid photographers. In Chapter Four, I examine the complex history of Cole’s book and how it can be read as a response to both the mundane brutality of apartheid and the limits of photographic humanism. Following a barren spell for political and cultural opposition to apartheid, the late 1970s and 1980s saw a resurgence and the development of a more politically focused collective photographic practice (Chapter Five). Associated particularly with Afrapix, an anti-apartheid photographic collective and picture agency, the emphasis in the 1980s was on a collective rather than individual practice. There was a self-conscious shift away from valuing the individual vision and creativity of the photographer, to asking how photography could be used as a tool of the struggle for liberation and democracy. Although some may have been ambivalent or even hostile to the title, this is often framed as ‘struggle photography’, where creativity was subservient to the needs of the liberation movement. As with Drum, though more explicitly, the emphasis on training black South African photographers was an important part of this practice. I also examine here the work of Eli Weinberg, a trade union activist photographing from the 1950s, which provides one of the earliest examples of ‘struggle photography’ and a precursor to the activist photographic tradition of the 1980s. Following his death in 1981, Weinberg’s archive was housed as part of the photographic collection of the London-based, anti- Introduction 10 apartheid International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF), which was central to the international distribution of images of the South African situation during the last years of apartheid, and has since become one of the most significant post-apartheid collections. The advent of democracy in South Africa in 1994 led to a re-appraisal of the role of photography; and, some might argue, its creative release from the oppression and discipline of the apartheid period. But this was also a moment when the images of the apartheid period began to be repositioned; often literally as they returned from exile to archives and collections in South Africa. Photographic archives were key repositories for imaging the past, and photographs taken for Drum or Afrapix became central to many exhibitions, memorials and museum displays, commemorating the victims of the past and presenting histories of the apartheid period. In 2001, for example, Cole’s House of Bondage was installed as an exhibit at a major museum in Johannesburg. In Chapter Six, taking the Apartheid Museum and the Hector Pieterson Museum as case studies, I consider this final transition, and the ways in which these images have been re-used and re-interpreted in post-apartheid South Africa. The new democratic South Africa provided a radically altered setting within which photographers had to work. As Santu Mofokeng has suggested, this presented a challenge for those who photographed during the apartheid years: ‘things have changed, it has become more difficult to legitimise my role as a documentary photographer in the traditional sense. As I get more intimate with my subjects, I find I cannot represent them in any meaningful way. I see my role becoming one of questioning rather than documenting’.36 And increasingly there are photographers for whom the new South Africa is not new at all, but the only South Africa they have known. Nevertheless, I believe this makes an understanding of the documentary photography of the apartheid period more, rather than less, important. In writing a history of photography during the apartheid period, I hope to inform debates about the purpose and direction of photography in the present. Knowledge of the medium’s past is a necessary condition for the development of a critical photographic practice, and can enable photographers, editors and curators to see the continuities as well as the discontinuities with the present. But it is more than that. Histories of photography have been dominated by examples from Europe and the US; where photographic historians have looked to Africa they have been selective, often searching for something essentially African. This book is not offered as some ‘other’ history of photography. The photography that developed in the unique circumstances of South Africa during the apartheid period deserves to be better known, its richness and sophistication more widely appreciated. Taken as a whole it offers a fascinating microcosm for examining the complex interrelationship between photography, society and politics, which remains central to any interpretation of the documentary image. There are moments in research when one is brought up short, moments when some incident or observation throws into sharp relief the whole of one’s investigation. I want to end this introduction with one such moment. In March 2004, I travelled to the township of Mamelodi on the eastern edge of Introduction 11 Pretoria in Gauteng, where Cole had lived in the 1960s. I had gone there to interview Geoff Mphakati, a close friend of Cole’s. We were discussing Cole’s book House of Bondage, when Geoff turned to me and asked what I saw when I came into the township, and what I saw in the other townships I had been through in South Africa. This reversal of the interview caught me by surprise, and my stuttered response, that I saw people living in difficult circumstances, seemed to both of us completely inadequate. The brief exchange exposed my position as an outsider, a white European researcher trying to make sense of images of the black townships of apartheid South Africa, and seemed to throw into doubt the very basis of such a project. Yet, on reflection, the question – ‘What do you see?’ – is significant in another sense. I was there because Cole had made the photographs he did, because in other words, he was compelled to show to others, in Europe and the US as well as South Africa, what he saw. It was this ‘invitation to pay attention, to reflect, to learn’ 37 that had brought me to South Africa, and this invitation to a dialogue about the world that is at the heart of documentary photography. In the pages that follow, I hope to do justice to the complex political, practical, ethical and aesthetic issues to which this simple question gives rise. 1 ‘Photography, Politics and Ethics’, University of the Witwatersrand, 12 March 2004. 2 Patricia Hayes used the phrase ‘agendas of visibility’. See P. Hayes, ‘Power, Secrecy, Proximity: A History of South African Photography’, in Zeitgenössiche Fotokunst Aus Südafrika (Contemporary Art Photography from South Africa), ed. A. Tolnay (Heidelberg: Neuer Berliner Kunstverein und Edition Braus im Wachter Verlag GmbH, 2007). 3 I. Walker, City Gorged with Dreams: Surrealism and Documentary Photography in Inter-War Paris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 4. 4 Roland Barthes’ damning critique of Edward Steichen’s Family of Man exhibition provides the paradigm example. See R. Barthes, Mythologies (London: Paladin, 1973), 109. I have always been dissatisfied with those critiques of documentary that seemed to argue that the supposedly ‘straight’ photographic image was inevitably aligned with an uncritical stance and that only the constructed image could serve a progressive political position. Such arguments draw on a partial reading of Walter Benjamin’s 1931 essay ‘A small history of photography’. See W. Benjamin, ‘A Small History of Photography’, in One Way Street and Other Writings (London: New Left Books, 1979), 240--57. 5 See, for example, O. Enwezor, Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography (New York and Göttingen: International Center for Photography and Steidl Publishers, 2006); C. Bell, O. Enwezor, D. Tilkin and O. Zaya, In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present, catalogue of exhibition held 24 May--29 September 1996, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, introduction by C. Bell and essays by O. Enwezor, O. Oguibe and O. Zaya (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1996); Revue Noire’s Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography (Paris: Revue Noire, 1999); T. Mieβgang and B. Schröder, Flash Afrique: Fotografie aus Westafrika (Göttingen: Steidl Verlag, 2001). 6 Revue Noire. 7 Drum, an illustrated magazine, was first published as The African Drum in Cape Town in March 1951. Introduction 12 8 O. Enwezor, ‘A Critical Presence: Drum Magazine in Context’, in In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present, ed. C. Bell et al (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1996), 182--90. 9 Ibid. 10 Ibid. 11 Ibid. 12 V. Rocco, ‘After In/sight: Ten Years of Exhibiting Contemporary African Photography’, in Enwezor, Snap Judgments, 350. 13 See, for example, Enwezor’s discussion of Kevin Carter’s Pulitzer prize-winning image of a Sudanese child dying of hunger, Snap Judgments, 17--18. 14 Enwezor, Snap Judgments, 45. 15 Enwezor further elaborates this argument in Snap Judgments. Echoing the thesis advanced in In/Sight, he suggests that ‘the paradigmatic shift from colonial and Western documentary photography in Africa to modern and contemporary African photography is captured in the attempt by African photographers and artists to re-establish the priority of an extant African visual archive’. But this conflation of colonial photography and the documentary tradition is problematic, and nowhere more so than in South Africa; see Enwezor, Snap Judgments, 28. 16 This approach offered a way out of the cul-de-sac which writing on colonial photography had reached, within which photographs were simply the index of social forces, and neither the subject nor the photographer had any agency within the photographic process. 17 Rocco, ‘After In/sight’, 350. 18 Enwezor, Snap Judgments, 25. 19 Ibid., 26. It may also be argued that the privileging of the portrait form in contemporary African photography, and the relative lack of landscape photography, may itself be a legacy of colonialism. 20 It is perhaps ironic that the dramatic example which Oguibe used to frame his argument was that of a migrant worker come to work in the mines in South Africa and wishing to send an image home to show how well he is doing in the city; see O. Oguibe, ‘The Photographic Experience: Toward an Understanding of Photography in Africa’, in Flash Afrique: Fotografie aus Westafrika, ed. T. Mieβgang and B. Schröder (Göttingen: Steidl Verlag, 2001), 117. The example comes from ‘Sizwe Bansi is Dead’, a play by Athol Fugard, John Kani and Winston Ntshona, first performed at The Space in Cape Town, 8 October 1972. 21 The valuing of vernacular photographic practices and the relationship between photography and self-fashioning is not exclusive to Africa. Chris Pinney’s seminal study of Indian photography is extremely important in this regard and forms part of the same postcolonial theoretical landscape as studies of West African portrait photography. See C. Pinney, Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs (London: Reaktion Books, 1997). See also H. Behrend, ‘“I Am Like a Movie Star in My Street”: Photographic Self-creation in Postcolonial Kenya’, in Postcolonial Subjectivities in Africa, ed. R. Werbner (London: Zed Books, 2002), 44--62. 22 There are some exceptions, such as Revue Noire’s more inclusive Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography; nevertheless, the accompanying critical-historical writing is not extensive. Introduction 13 23 This is not the place for a long discussion of South African national identity, but writing in the 1960s Nat Nakasa offered a definition that carries the complexity and emphasis that I wish to invoke here: ‘Who are my people? I am supposed to be a Pondo, but I don’t even know the language of that tribe. I was brought up in a Zulu-speaking home, my mother being a Zulu. Yet I can no longer think in Zulu because that language cannot cope with the demands of our day. I could not, for instance, discuss negritude in Zulu . . . I have never owned an assegai or any of the magnificent tribal shields . . . I am more at home with an Afrikaner than with a West African. I am a South African . . . “My people” are South Africans. Mine is the history of the Great Trek. Gandhi’s passive resistance in Johannesburg, the wars of Atewayo and the dawn raids which gave us the treason trials in 1956. All these are South African things. They are a part of me’, N. Nakasa cited in United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), Apartheid, Its Effects on Education, Science, Culture and Information (Paris: UNESCO, 1967), 180. 24 W. Beinart, Twentieth Century South Africa, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 144. 25 Ibid. 26 Ibid. 27 F. Welsh, A History of South Africa (London: Harper Collins, 2000), 428. 28 In discussing South Africa under apartheid it is occasionally necessary to resort to the official racial terminology used by the Nationalist government. 29 Beinart, Twentieth Century South Africa, 160. 30 Ibid. 31 Ibid., 152. 32 Anthony Sampson interviewed by Darren Newbury, Westbourne Grove, London, 19 December 2003. 33 E. Cole, House of Bondage (A Ridge Press Book, New York: Random House, 1967). 34 P. Bonner, ‘The Politics of Black Squatter Movements on the Rand, 1944--52’, Radical History Review, 46--47 (1990b):92. 35 Beinart, Twentieth Century South Africa, 144--5. 36 S. Mofokeng, cited in O. Enwezor and O. Zaya, ‘Colonial Imaginary, Tropes of Disruption: History, Culture, and Representation in the works of African photographers’, in In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present, ed. C. Bell et al (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1996), 22. 37 S. Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 117. Introduction 14