thesis - Fire Archaeology

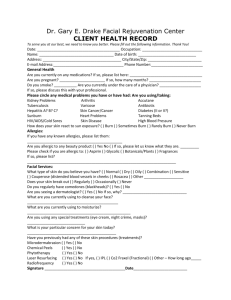

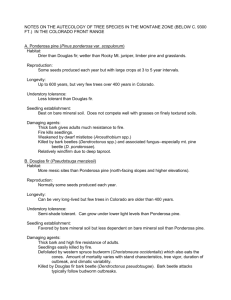

advertisement