chapter28

advertisement

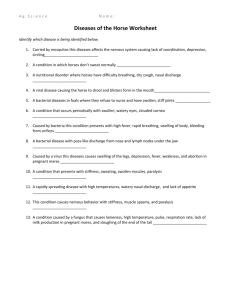

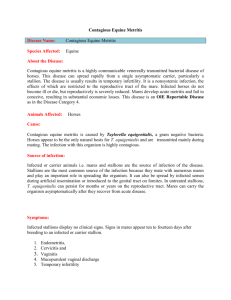

‘... Sisyphos’ son Glaukos was killed by [his] horses at the time Akastos organized funeral games to honour his father’ (Pausanias 6.20.19) Epilogue 28. CRAZY HORSES IN GREEK MYTHS: A PREVIEW OF “MAD COWS?” It is tempting to suggest that if modern cattle and horse breeders in Great Britain or elsewhere had taken some time to study Greek mythology, they could have prevented such phenomena as ‘mad cow disease’ and similar ailments in other animals. This statement may seem incredible but it is justified. The Greek tragedians included elements of ancient myths in their plays, and, although they were not breeders or veterinary experts, at least two Greek poets, Aischylos and Euripides, as well as the historians Apollodoros and Diodoros, dealt with ‘crazy horses’ in detail and arrived at identical conclusions. It comes as no surprise that all of them, like contemporary Hellenes, accepted as an inviolable moral principle of Nature that the human hubris of feeding meat to herbivorous animals must lead inevitably to tragedy and disaster. If we briefly revisit the ancient myths and the works of the two tragedians, we discover that they predicted the noxious consequences of man’s arrogant disregard of Nature. In Aischylos’ lost tragedy Glaukos Potnieus, which was part of his tetralogy (with Fineus, Perses and Prometheus Pyrophoros) and won the first prize at the Dionysia festival of 472 BCE, the eponymous hero lived in Boiotia and bred ‘savage’ mares. In order to make them more ‘warlike’, Glaukos fed them with human flesh. When the son of Sisyphos and Merope went to Iolkos to take part in the funeral games held by Akastos in honour of his father Pelias, these mares in their frenzy at not finding their customary food in the fields of the Thessalian city, devoured their owner. In another version of the same myth the mares were turned crazy by Aphrodite, who had been enraged by Glaukos’ treatment of his own animals. Glaukos, it seems, had never permitted his mares to breed with stallions for fear that they would lose their speed! Whether the cause of the mares’ madness was the flesh on which they had been fed, or frustrated maternal instinct, in either case, it was man’s hubris in the face of the gods and nature. Interestingly enough Glaukos was later worshipped by the Corinthians under the name of Taraxippos (horse terrorizer, see Chapter 17). In fact, every contestant at the Isthmian horse races would sacrifice to Glaukos, prior to the games, in order to appease him (Pausanias 6.20.19): ‘There is Τaraxippos at the Isthmus, the son of Sisyphus Glaukos’ 1 A similar myth to that of Glaukos’ Boiotian mares was recorded by Euripides in Alkestis which refers to the eighth athlon of Herakles. The renowned Greek hero was ordered by Eurystheus to bring to him the horses of Diomedes, son of the Olympian god Ares and king of Thrace. Diomedes had four mares, which were wild and, fittingly, bore masculine names, Podargos, Lampon, Xanthos and Deinos. The mares were not fed hay but were given human flesh instead. Each time a xenos (foreigner) arrived in Thrace, Diomedes would kill the intruder and cut his body in pieces, throwing them to the four horses. The meat turned the mares so savage that the king was forced to keep them tethered with iron chains and post armed guards around the stable. Herakles realizing the enormity of the task, extended an invitation to any riend who was brave enough to meet the challenge. Several heroes responded, among them young Abderos from Lokris, a purported son of Poseidon. The men sailed to Thrace via the isle of Thasos and, in a lightning strike Herakles killed Diomedes’ guards, took the man-eating mares back to his ship, and asked Abderos to guard them. As soon as he saw the guards dying and his mares gone, Diomedes, ordered his army to pursue Herakles. Leaving the horses in the safe hands of Abderos, Herakles rushed back to face Diomedes and, aided by his brave companions, killed him with his club. Having accomplished his mission, the hero and his companions returned to the shore where they were shocked by a horrible sight. The mares of Diomedes had devoured Abderos. Herakles could find only a few parts of the body and these he buried on the spot. To honor his friend he founded the city of Abdera and instituted athletic contests to be held annually. The mares were taken back to Mykenai where, surprisingly, king Eurystheus allowed them to roam free. They wandered throughout Greece, finally reaching Olympus in the north where they were devoured by wild beasts (probably lions). In another version of the myth, at once more interesting and plausible, Herakles reached Thrace on foot and alone. His plan to secure the mares was simple: he wrestled Diomedes, defeated him, and threw him to the mares, who devoured him (Fig. 28.1). As soon as the animals had eaten the cruel king they became docile, thus making it easy for Herakles to lead them back to the city of Mykenai. King Eurystheus was so happy with the gentle mares that he offered them to the goddess Hera. Surprisingly the goddess, a sworn enemy of Herakles, accepted the gift from King Eurystheus, and set the horses free. These mares, according to Diodoros (4.15.3), foaled a great number of colts and fillies with later generations spreading throughout Greece down to the time of the Macedonians, their numbers supplying the cavalry of Alexander Great: ‘…when the horses were brought to Eurystheus, he rendered them sacred to Hera. The breed of these mares reached in fact [the times of] Alexander’s reign’ Thus, thanks to Diodoros, we know the genitors of the Macedonian cavalry horses: the man-eating mares of king Diomedes of Thrace. After being tamed by Herakles, they were taken to Peloponnesos, set free by Hera, and roamed back to the north reaching Thessaly and Macedonia. 2 At the same time, we should be grateful to Aischylos and Euripides for demonstrating that, when Nature is violated by Man, the gods respond to such hubris by rendering the animals crazy. God may forgive always, man may be able to forgive from time to time, but Nature reacts harshly to every blasphemy committed by humans—and never forgives. There is a hard lesson to learn from the Greek tragedians and their poetry. In our days, people have reverted to eating horses for fear of the BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy). Horses and ponies are being exported or, worse, stolen, to supply the kitchens of ‘modern’ consumers. This is exactly how men treated horses some 40,000 years ago, hunting them for their flesh. Then came the time for the Mesopotamians, Assyrians, Hittites and Egyptians to turn the horse into a war machine. Finally, it was the culture of the Hellenes, who gave wings to Pegasus, had him bridled by Athena, and turned their stallions, mares, colts, fillies and mules into Olympic athletes for thirteen centuries. Several eons later, in our present days, Homo erectus europeensis has taken a giant step backwards, and, as a result of his blasphemy, has regressed to eating horses. Greeks and Portuguese (who are among the few people who abstain from eating horse flesh) consider this as cruelty and most uncivilized behavior. I concur. Fig 28.1 Black-figured kylix, ca. 510-500 BCE, Ermitage, St. Petersburg. Αn iconographic presentation of the eighth athlon of Herakles, which is much earlier than the literary ones. The Greek hero is seen holding a stallion with his right hand and at the same time threatening the animal with his club. The horse seems trying to escape in fast gallop, and out of his mouth the remains of a man (Abderos or Diomedes) are discernible 3