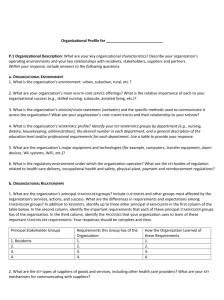

Stakes and Stakeholders - Boston College Personal Web Server

advertisement