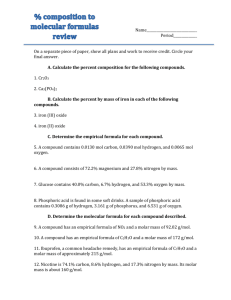

Chapter 3: Formulas, Equations, & Moles

advertisement

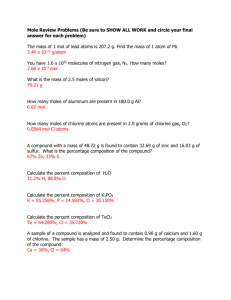

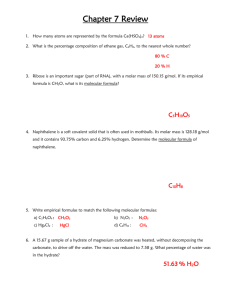

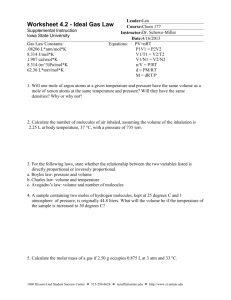

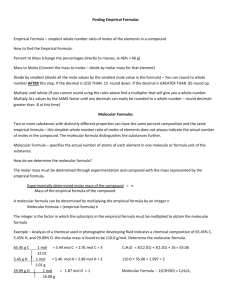

20 Chapter 3: Molecules, Compounds, & Chemical Equations I) Chemical Bonds 1) Compounds are composed of atoms held together by chemical bonds. 2) The interaction of electrons between elements is what results in chemical bonding. 3) Two broad types of chemical bonds. A) Ionic Bonding involves the transfer of electrons from a metal to a nonmetal. B) Covalent Bonding involves the sharing of electrons between nonmetal atoms. II) Chemical Formulas: Representing Compounds 1) Compounds are most easily represented using chemical formulas for the individual constituent elements and whole number subscripts to denote how many atoms of that element are present. 2) Types of Chemical Formulas A) empirical formula - simplest whole # ratio of atoms in a compound. B) molecular formula i) true formula for a compound ii) actual whole # ratio of atoms in a compound ii) usually a multiple of the empirical formula C) structural formula i) shows connectivity of atoms using dashed lines to denote covalent bonds ii) be able to distinguish between single bonds ( ─ ), double bonds ( = ), and triple bonds ( ≡ ) 3) Molecular Models A) Ball-and-Stick models represent atoms as spheres and chemical bonds as sticks; how the two connect reflects a molecule’s shape. B) Space-filling models are so named because the atoms fill the space between them and are our best estimate of how a molecule might appear to us. 21 III) Classifying Matter Revisited: An Atomic Level View 1) Review Figure 3.4 as well as definitions for pure substance, element, and compound. 2) Atomic vs. Molecular Elements A) Atomic elements are those that exist in nature with single atoms as their base units. Most elements fall into this category. B) Molecular elements exist as molecules in nature and not as atoms. These are called the diatomic molecules (H2, N2, O2, F2, Cl2, Br2, I2) and the polyatomic molecules (P4, S8, Se). 3) Covalent Bonds: Molecular Compounds A) Covalent bonding results when electrons are shared between nonmetal atoms. B) Molecule - two or more covalently bonded atoms. C) Molecular compounds have covalently bonded molecules as their building blocks 4) Ionic Bonds: Ionic Compounds A) An ionic bond results from a transfer of electrons from one atom to another. The transfer, usually from the metal to a nonmetal, results in the formation of ions. B) ion - charged atom or group of atoms. There are two types of ions. i) Cations: ii) Anions: lose electrons gain electrons (+) ion (- ) ion metals nonmetals C) The basic unit for an ionic compound is the formula unit which is the smallest electrically neutral collection of ions. D) A polyatomic ion is a charged group of covalently bonded atoms. IV) The Language of Chemistry: Naming Compounds 1) It is imperative to remember that compounds are chemically neutral; that means that all the positive charges must be equally balanced with all negative charges that are present. 22 2) Binary Ionic Compounds A) Binary Compounds have two parts. B) To name a binary ionic compound i) ii) iii) First identify the positive ion and the negative ion. The positive ion, usually a metal cation, is named first and is the same as the name of the element. The negative ion, usually a nonmetal, is named second. Here the name of the nonmetal element is used, but the ending is changed to –ide. C) Examples i) KCl ii) CaF2 iii) BaO potassium chloride calcium fluoride barium oxide D) Study Tables 3.2 through 3.5 and commit these to memory! 3) Ionic Compounds with a Transition Metal Cation A) Some metals form more than one type of cation. These are typically found in the transition metals. B) To avoid confusion when naming ionic compounds that contain a transition metal cation, the charge of the metal cation is enclosed in parenthesis as a Roman numeral. The remaining rules for naming a binary ionic compound are the same as shown above. C) An older system uses the endings –ous and –ic to denote the different charges on a transition metal. The metal cation with the higher charge takes the –ic ending. D) Examples i) ii) FeCl2 FeCl3 Iron (II) chloride Iron (III) chloride Ferrous chloride Ferric chloride 4) Naming Binary Molecular (Covalent) Compounds A) To name a binary covalent compound i) Find which nonmetal element is more cationlike from its position in the periodic table. This nonmetal is named first in the same fashion as a metallic cation. The other nonmetal is named as the anion with the –ide ending. 23 ii) iii) iv) Use Greek prefixes to account for # atoms in both nonmetals. If first element contains only 1 atom, drop mono prefix. Be familiar with Greek prefixes (see section 3.6). B) Examples i) CS2 ii) SO2 iii) PCl5 iv) N2O4 carbon disulfide sulfur dioxide phosphorus pentachloride dinitrogen tetroxide (dinitrogen tetraoxide) 5) Naming Compounds that contain Polyatomic Cations and Anions A) Compounds that contain polyatomic cations or anions are named exactly as shown in Table 3.5. B) Must commit to memory the name, formula, and charges for the cations and anions in Tables 3.2 to 3.5. C) Examples i) NaNO3 ii) (NH4)2SO4 iii) KC2H3O2 sodium nitrate ammonium sulfate potassium acetate 6) Naming Hydrates A) Hydrates are compounds that contain a specific number of water molecules (called waters of hydration) associated with each formula unit. B) Waters of hydration can be removed by heating a hydrate, the resulting product is the anhydrous salt (anhydrous means without water). C) Examples i) Na2CrO4 * 4H2O ii) BaCl2 * 2H2O sodium chromate tetrahydrate barium chloride dihydrate V) Acids & Bases: An Introduction 1) An acid is a substance that produces hydrogen ions (H+ ions) when dissolved in water. A) Binary acids named using the form hydro + nonmetal + -ic ending. B) Examples i) HCl ii) HF hydrochloric acid hydrofluoric acid 24 2) Most acids are oxyacids meaning that they contain hydrogen and an oxyanion (an anion containing a nonmetal and oxygen). A) Common oxyanions listed in Table 3.5. B) Review oxyanions and be familiar with various prefix & suffix rules. i) ii) iii) The –ate ending is found with the oxoanion that has the higher number of oxygen atoms. The –ite ending is found with the oxoanion that has the lower number of oxygen atoms. If there are more than two members in a series, then one must also be familiar with when to use the prefix per- and when to use the prefix hypo-. C) Naming oxyacids i) If oxyanion base name ends in –ate then the acid name takes the form base name of oxyanion + -ic acid. Examples: ii) HNO3 H2SO4 nitric acid sulfuric acid If oxyanion base name ends in –ite then the acid name takes the form base name of oxyanion + -ous acid. Examples: HNO2 H2SO3 nitrous acid sulfurous acid 3) A base is a substance that produces hydroxide ions (OH- ions) when dissolved in water. A) Bases are often named as metal hydroxides (the word hydroxide appears in the name). B) Examples: i) lithium hydroxide ii) sodium hydroxide iii) potassium hydroxide LiOH NaOH KOH VI) Formula Mass & Mole Concept for Compounds 1) Recall from chapter 2 that the formula mass (FM) represents the sum of atomic masses of all atoms in a formula unit of any compound (ionic or molecular). 25 2) Other terms that are equivalent to formula mass include molecular mass, molecular weight, and formula weight. Each of these refer to the same calculation. 3) To calculate formula mass (FM), one uses the following formula. FM = Σ (# atoms of each element in formula * atomic mass each element) 4) Example Formula Mass of Water (H2O): FM = (2 x 1.01 amu) + (16.00 amu) = 18.02 amu Formula Mass Carbon Dioxide (CO2): FM = (12.01 amu) + (2 x 16.00 amu) = 44.01 amu 5) Recall also from chapter 2 that chemists rely on the mole as the basis for measuring the amounts of substances. 1 mole of X = NA units (units = atoms, ions, molecules) NA = Avogadro’s Number = 6.022 x 1023 units/mole mass of 1 mole of a substance X = molar mass of X in grams. Molar mass is equal to formula (molecular) mass of X in grams. Molar mass values are expressed in grams/mole. VII) Composition of Compounds 1) Ways of Describing Composition of a Compound A) number of atoms in chemical formula B) % by mass of elements (called a mass % or weight %) mass % of element X = (mass of element X in compound / total mass) * 100% 2) Example Calculations A) Ethyl Alcohol C2H5OH ? % C, % H, and % O in compound 1 mole ethyl alcohol = 2 mole C = 6 mole H = 1 mole O MM: [(2 mol x 12.01 g/mol) + (6 mol x 1.008 g/mol) + (1 mol x 16.00g/mol)] 26 MM ethyl alcohol = [ 24.02 g + 6.048 g + 16.00 g] = 46.07 g === 1 mole MM ethyl alcohol = 46.07 g /mole 46.07 g == 1 mole Mass % = (mass X / total mass) * 100 % C = (24.02 g / 46.07 g) * 100 % = 52.14% C % H = (6.048 g / 46.07 g) * 100% = 13.13% H %O = (16.00 g / 46.07 g) * 100 % = 34.73% O 100.00 % B) Carvone MM of Carvone C10H14O ? %, C, H, and O 1 mole Carvone = 10 mol C = 14 mol H = 1 mol O MM = [(10 mol C x 12.01 g/mol) + (14 mol H x 1.008 g/mol) + (1 mol O x 16.00 g/mol)] MM Carvone = [ 120.1 g + 14.11 g + 16.00 g] = 150.2 g Carvone === 1 mole MM Carvone = 150.2 g /mole 150.2 g === 1 mole % C = (120.1 g / 150.2 g) * 100% = 79.96 % C % H = (14.11 g / 150.2 g) * 100% = 9.394% H % O = (16.00 g / 150.2 g) * 100% = 10.65% O 100.00% 3) The mass percent composition of an element in a compound is a conversion factor between the mass of the element and mass of the compound. 4) Always keep in mind that percent means per hundred, so we know for example that in 100.00 g of Carvone, there are 79.96 g of carbon. 100.00 g Carvone : 79.96 g carbon 5) Since chemical formulas contain within them inherent relationships between atoms (or moles of atoms) and molecules (or moles of molecules), we can use these to find mass. The general approach often uses the following concept map. Mass compound → moles compound → moles element → mass element 27 VIII) Determining Formula of a Compound 1) Terminology A) empirical formula - simplest whole # ratio of atoms in a compound. B) molecular formula i) true formula for a compound. ii) usually a multiple of the empirical formula iii) must be given MM to figure out the multiple factor. 2) Methods for Determining Formulas from % Composition A) Example Problem Given & Unknowns: 71.65 % Cl 24.27 % C 4.07% H Solutions: MM of compound = 98.96 g/mol ? empirical formula ? molecular formula Two Methodologies Method 1: Traditional Approach (Works Every Single Time) Step 1: Assume 100.00 g sample of compound (Why?) [% s = mass of element (g)] 71.65 g Cl x ( 1 mol Cl / 35.45 g Cl) = 2.021 mol Cl 24.27 g C x ( 1 mol C / 12.01 g C) = 2.021 mol C 4.07 g H ( 1 mol H / 1.008 g H) = 4.04 mol H Note: Although one expresses the intermediate # moles to the proper # sig. figs., always remember the DNRUD principle!!! Step 2: Divide # moles obtained from step 1 by smallest # moles present. This gives the number of atoms present. 2.021 mol Cl / 2.021 mol = 1.000 Cl atoms 2.021 mol C / 2.021 mol = 1.000 C atoms 28 4.04 mol H / 2.021 mol = 2.00 H atoms Note: If one obtains a value that is very close to the next whole # (e.g., 1.98 or 2.03), then one may round those values to the next whole number. DO NOT round values like 2.5, 3.67, 1.33, etc. to the nearest whole number.... Step 3: Check to see that # atoms from step 2 is a whole # for each entry. If so, then one has the empirical formula directly. If the values are not whole #s, one must now introduce a factor to convert the values to whole #s. Since # atoms above are all whole #s, the empirical formula is CH2Cl Step 4: Using the empirical formula obtained in step 3, find empirical MM (molecular mass corresponding to the given empirical formula). From that value, one finds molecular formula by using the molecular MM (must be given in problem) as shown in the following equation empirical MM (x) = molecular MM where x is the factor that must be used to go from empirical formula to molecular formula. Empirical MM = [ (1 x 12.01 g/mol) + (2 x 1.008 g/mol) + (1 x 35.45 g/mol)] Empirical MM = (12.01 g/mol + 2.016 g/mol + 35.45 g/mol) = 49.48 g/mol 49.48 g/mol (x) = 98.96 g/mol x = 2.00 Step 5: Once the factor (x) is known, simply plug into equation shown below and write out the molecular formula Molecular formula = (Empirical formula) * x. Molecular Formula = (CH2Cl) * 2 = C2H4Cl2 = Answer _____________________________________________________________________ 29 Method 2: Combustion Analysis involves burning a sample in the presence of pure oxygen and isolating the products CO2 and H2O. The mass of each product is obtained and from this data the empirical formula is evaluated. Step 1: Write as given the masses of each combustion product (CO2 and H2O) along with mass of sample if it is provided. Step 2: Convert mass of CO2 and H2O to moles using molar mass values for CO2 and H2O. Step 3: Convert moles of CO2 and H2O from step 2 to moles of C and H using chemical formulas for CO2 and H2O. Step 4: If the compound contains an element other than C and H, find the mass of the other element by subtracting the sum of the masses of C and H (obtained in step 3) from the mass of the sample. Finally convert the mass of the other element to moles. Step 5: Divide # moles obtained for each element by smallest # moles present. This gives the number of atoms present. Step 6: Check to see that # atoms from step 5 is a whole # for each entry. If so, then one has the empirical formula directly. If the values are not whole #s, one must now introduce a factor to convert the values to whole #s. Review Example Problem 3.19 & 3.20 IX) Chemical Reactions: 1. Components of a Chemical Equation A) Reactants (left side) B) Arrow (produces or yields) C) Products (right side) D) Physical States (s) = solid, (l) = liquid, (g)=gas, (aq) = aqueous E) Other information (catalysts, temperature, pressure, etc.) 2) Example Reaction A) Combustion of Methane CH4 (g) + O2 (g) ------> CO2 (g) + H2O (g) 3) Characteristics Shared by All Reactions A) Bonds are broken; atoms rearrange; new bonds are formed 30 B) Conservation of Matter must hold true. i) All reactions must be balanced! ii) Balancing a chemical reaction involves finding out how many formula units of each different substance takes part in the reaction. A formula unit is one unit, (atom, molecule, or ion), corresponding to a given formula. Most simple chemical reactions can be balanced by inspection. Ex: CH4 (g) + 2 O2 (g) ------> CO2 (g) + 2 H2O (g) 1C 4H 4O 1C 4H 4O iii) Use coefficients (written in front of reactant or product) to balance the reaction. iv) Only coefficients can be changed when balancing an equation; the formulas themselves can not be changed. v) Any species that lacks a coefficient is ALWAYS understood to be 1. The coefficient 1 is NEVER written in a chemical reaction... vi) Get into habit of checking your reactions to see that all atoms are balanced. 4) Reaction Classification (General Scheme) A) 4 Main Classes of Reactions (A + B AB) (AB A + B) i) Synthesis (Combination) ii) Decomposition - heat required for decomposition reactions. iii) Single Replacement iv) Double Replacement (A + BC ------> AC + B) (AB + CD ------> AD + CB) - also termed metathesis reaction. 31 5) Methodology for Balancing Chemical Reactions A) Write out reaction correctly, including all necessary information about the reaction. Determine what is occurring. B) Construct the table listing the individual elements and how many of each species is initially present. C) Balance the reaction using whole number coefficients. Keep track of how many atoms are present once the coefficients are changed (coefficients affect the entire reactant or product species). D) As a general rule, start with most complicated molecule or an item that appears by itself on either side of the reaction. E) Examples C2H5OH (l) + O2 (g) -------> CO2 (g) + H2O (g) 2C 6H 7O i) Balance C first ii) Balance H next iii) Balance O next 2C 6H 7O (need 2 in front of C product) (need 3 in front of H product) (need 3 in front of oxygen reactant) C2H5OH (l) + 3 O2 (g) -------> 2 CO2 (g) + 3 H2O (g) iv) check to make sure it is balanced 2C 6H 7O 2C 6H 7O Example 2 heat (NH4)2Cr2O7 (s) Cr2O3 (s) + N2 (g) + H2O (g) 2N 2 Cr 7O 8H 2N 2 Cr 4O 2H i) Cr and N are already balanced, so leave them alone. ii) Balance H next (place 4 in front of water) 32 iii) O is balanced once coefficient is placed in front of water. heat (NH4)2Cr2O7 (s) Cr2O3 (s) + N2 (g) + 4 H2O (g) iv) Check your answer! 2N 2 Cr 7O 8H 2N 2 Cr 7O 8H X) Introduction to Organic Compounds 1) Combustion reactions involve an organic compound reacting with oxygen to form carbon dioxide and water. 2) Organic chemistry investigates the chemistry of carbon containing compounds. A) Carbon is essential to all life. B) Carbon is unique because it has the ability to bond with itself forming chain, branched, and ring structures. C) Carbon always forms four bonds. 3) Organic compounds that contain only carbon and hydrogen are called hydrocarbons. A) Alkanes contain only C-C single bonds. B) Alkenes contain one C=C double bond. C) Alkynes contain one C ≡ C triple bond. 4) Functionalized hydrocarbons contain a functional group which is a characteristic atom or group of atoms that are incorporated into the hydrocarbon. 5) The functional group gives rise to the unique chemistry found in each organic family. 6) Know Table 3.8 and be able to recognize organic functional groups.