Amin - PTC Wind Energy

advertisement

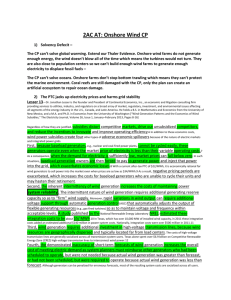

Meeren Amin Energy Law Professor Palmiter, Fall 2011 I. Introduction Wind power is the future of energy in the United States. It is clean, renewable, and relatively cheap. For years, the U.S. has wanted to reduce its dependence on both foreign energy sources and carbon emitting coal, in favor of green, renewable energy. Over the past thirty years, the U.S. has shifted towards this goal by incentivizing wind energy. Wind energy was introduced in the 1980’s in California and Denmark. Early turbines were expensive and inefficient. Today, however, wind power has become more efficient and less expensive through improvements in technology. As costs have declined, companies have become less hesitant to invest in large wind projects. It is now the fastest growing source of new power generation in the U.S. and the leading form of alternative energy. However, even with increased growth, wind energy accounts for only 1% of all electricity generated in the country. This low percentage is attributed to the high cost of large wind projects. Power companies and investors are more eager to invest in coal and natural gas sources, due to large, long-term government subsidies. As this paper will discuss, while subsidies—through the use of the Production Tax Credit (“PTC”)—are also available to wind producers, they offer only short-term benefits, discouraging long-term investment. Without long-term incentives, firms are unwilling to make large investments in a wind infrastructure, due to an uncertain future market. This paper will analyze the PTC and offer recommendations to allow it to reach its full potential of incentivizing the production of wind power. It will focus on the problem of shortterm extensions, but will not discuss design defects or limitations on availability. First, it will discuss why wind energy is important for America’s energy future. Next, it will provide an overview of the PTC and discuss its impacts on wind investment. It will then discuss the problem of providing short-term extensions and offer a long-term solution. Lastly, it will briefly discuss the lack of investment in the nation’s transmission infrastructure. II. Why Wind Energy? Wind energy is said to have many benefits over traditional sources of electricity production, such as coal. It is renewable and uses the movement of the air to generate power. It does not rely on a mineral found in the earth, which must be mined and extracted. It is therefore a free fuel, which guarantees supply and eliminates large mining and transportation costs. Because it relies on the wind, supply will always be steady and prices will therefore be stable. However, the most important benefit to using wind energy is that it is “clean.” It does not produce harmful emissions and will allow the U.S. to decrease its production of harmful C02, which can lead to long-term climate change. Global climate change is currently one of the biggest issues facing our planet. It is well accepted by many in the scientific community, that for whatever reason, average world temperatures are increasing and will continue to increase. Since 1880, temperatures have increased by 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates a temperature rise of 3.2 to 7.1 degrees by the end of the century. This would wipe out over 30 percent of all animal and plant species, lead to famine and flooding, and have many other adverse consequences. One of the major culprits of global warming is C02 emitted from cars and the burning of coal. The atmosphere cannot handle all of the C02 being emitted from anthropogenic sources. In order to decrease the amount of C02 released into the atmosphere, and thus slow down or stop global warming, the U.S. and other large industrialized countries must limit the burning of coal. The easiest way to decrease C02 production would be to switch to wind energy. Currently, the energy [electric power?] industry is responsible for 40 percent of all C02 emissions. By switching to wind energy, that number could end up near zero. A wind turbine does not emit any C02 and within three to six months of operation, it will offset all emissions caused by construction. Therefore, for the rest of its projected twenty-year life, it will produce carbon-free electricity. In fact, through the use of wind power, the global wind industry has set the goal of saving 10 billion tons of C02 by 2020. The Global Wind Energy Council believes that this goal is likely to be met through the increased use of wind energy. III. The Production Tax Credit The PTC was created by the Energy Policy Act of 1992, which sought to stimulate the use of renewable technology. The PTC provides a tax credit of 2.2 cents per kilowatt-hour (“kWh”) to independent power producers (IPPs). It was created in order to subsidize the emerging wind industry and close the cost gap between renewable energy and traditional forms of power generation. The credit acts as a subsidy, giving IPPs a 2.2 cent credit for each kilowatt hour generated for a facility’s first ten years of operation. It was originally codified to give a 1.5 cent credit, but has been adjusted upwards due to inflation. The credit is available to companies that generate wind, solar, geothermal, and closed-loop bio energy. It is only available to producers that sell the electricity to independent third parties, thereby making it available only available to IPPs and not to investor owned utilities (“IOUs”). This results in the credit being unavailable to those that do not pay taxes, such as rural electric cooperatives, non-profits, and publicly owned utilities. Since 1992, the PTC has expired three times, and has been extended on five occasions. However, the credit has lapsed for six months, two months, and nine months, in 2000, 2002, and 2004, respectively. During each of these periods, there has been no credit available to producers of wind energy. Each lapse occurred because of Congress’ failure to extend the credit past its expiration date. Throughout the credit’s history, Congress has only extended its viability for 1–2 year periods. It was most recently extended in 2009 as part of the federal stimulus package, but is set to expire again at the end of 2012 if Congress is unable to reach an agreement. The result would be a temporary or permanent end to the PTC. With expiration looming, stakeholders in the wind industry are running to Congress to secure an extension by the end of the year, in order to eliminate potential market uncertainty. H.R. 3307, which extends the PTC an additional four years to the end of 2017, is currently in the House Ways and Means Committee. This bill, if passed, would create the longest PTC extension in recent history, and allow wind investors to secure the credit until the end of 2017. In opposition to H.R. 3307, H.R. 3308 eliminates the PTC. The bill would cut $90 billion in energy tax subsidies over the next ten years, while reducing corporate tax rates at the same time. The bill would cut a vast majority of the government’s support for renewable energy projects. IV. Impact of the PTC When it comes to total wind power produced, the United States is second to only China, which only recently took over the top spot. While the typical price for producing a kWh of wind energy is about 6–7 cents, the PTC reduces the cost by 2.2 cents/kWh, which is roughly one third of the total price per hour. This decreased cost creates an incentive for firms to invest in wind and allows for wind power to compete more successfully with traditional fossil fuels that also receive large subsidies. Since the PTC’s inception, the use of wind energy has greatly increased, with an aggregate investment of over $13 billion. Wind capacity has increased every year from 1997, with the exception of years in which the PTC has lapsed. It is no coincidence that this increase began the year that the PTC went into effect. Before the PTC, annual wind capacity in the U.S. was consistently under 500 MW. However, after passage, this number steadily grew, and in 2008 it reached over 8,000 MW. This number will continue to climb as the cost of production decreases. The true impact of the PTC can be seen during the lapse years of 2000, 2002, and 2004. The credit has expired three times and for periods ranging from 3–9 months, there has been no PTC available to wind producers. Investment has fallen drastically when the credit has expired, as investors have been uncertain about the future of the credit. In lapse years, investment fell 73– 93%. This is not an indication that investors were simply waiting for the PTC to be reapplied, as each time it expired, there was uncertainty about its return. There was no evidence indicating that the PTC would be reapplied, causing firms to halt investment to pre-PTC levels. During these lapse years, annual installed capacity fell back down to below 500 MW. The years following the lapse, installed capacity rose back up to above 1,500 MW in 2001 and 2003, and close to 2,500 in 2005. The dramatic decrease in investment during lapse years shows that companies are unable and unwilling to invest in wind projects without the PTC. V. Short Term Extensions While the PTC promotes wind investment, providing only short-term extensions before expiration limits its potential. Every time the PTC has been extended, it has been for short 1–2 year periods. This has led to boom and bust cycles of “tight and frenzied” periods of development. During years of PTC viability, investors fear its long-term existence, causing a scramble on investment. Because firms want to invest in wind, they attempt to take advantage of the credit by investing in wind projects during the extension period and then almost completely chilling investment when the credit lapses. They are hesitant to devote resources to the production of wind energy without the certainty of long-term credits. Short-term credits restrict the ability of investors and manufacturers by creating future market uncertainty, which has adverse effects on investment, cost, commitment to transmission infrastructure, manufacturing, and R&D. There are five ways in which temporary 1–2 year extensions can hinder the effectiveness of the PTC. First, the risk of PTC expiration can slow wind development in certain years. Wind technology is an expensive and risky investment. Wind projects require extensive planning and take years to complete. Without the proper time to plan, research and implement a project, companies will be less likely to invest in a venture. Second, the temporary extensions have raised project costs. The cost of wind projects decreased substantially between the 1980s and early 2000s, but even with improved technology, they have increased since 2002. While the market crash of 2008 has had an effect on prices, the greatest effect has been the “erratic market cycle of frenzied investment.” Without an ability to project future earnings, supply and operation costs have increased. Third, U.S. firms have either slowed manufacturing of equipment or shifted focus overseas. U.S. companies have been hesitant to manufacture wind technology for domestic projects due to future uncertainty. Domestic manufacturers are unable to accurately determine future demand due to insecurity in the wind market. Foreign, state-backed firms have taken their place to provide more expensive technology. These firms are able to manufacture technology for their respective domestic markets and are backed by national governments, allowing them to take speculative risks in the U.S. wind market. Domestic companies, which do not have such backing, are unable to take the same risk. Fourth, the U.S. has under-invested in the transmission grid in recent years. Without the ability to predict the future growth in wind technology, FERC and the states have been unwilling to invest in the expensive transmission infrastructure necessary to expand availability of wind power. While effective transmission exists in certain regions in the country where wind power is already prevalent, the lack of investment in a more whole scale manner greatly limits the willingness of investors to engage in wind projects. Lastly, short-term PTC extensions decrease the willingness of private firms from investing in long-term wind technology R&D. Alternative energy R&D is seen as a long-term investment, and with the wind market predictable for only a year or two at a time, companies do not have an incentive to engage in long term technological research. VI. Solution: 10 Year Extension With the inadequacy of the short-term PTC, the most practical alternative would be a 10year extension of the PTC, upon expiration at the end of 2012. A longer-term PTC could lead to a more stabilized wind market that could encourage investment and drive down the cost of wind energy. A study conducted at Berkley National Laboratory suggests that a longer-term PTC could drive down the cost of wind energy and increase availability. The study found that a 5–10 year extension would 1) have diverse benefits; 2) increase growth in domestic wind turbine manufacturing; 3) encourage R&D; and 4) significantly reduce installation prices. The study found that the most important benefit to a longer-term PTC would be the greater number of wind installations resulting from policy stability. The boom and bust cycle would end, as a long-term guarantee would allow for firms to make informed investments over a ten-year period, rather than a short 1–2 year window. A ten-year extension promotes long-term planning by a firm and encourages large-scale projects that would be infeasible to accomplish in a short credit availability window. While impossible to tell exactly how much investment would increase by, it is estimated that just a four-year extension would increase PTC claims by about $4 billion. [source?] A ten-year extension would likely increase claims by even more, potentially creating greater stability in the wind market. The second benefit is an increase in domestic turbine manufacturing. A long-term PTC would encourage investment in manufacturing, as firms would be able to more easily calculate long-term demand, by planning for a ten-year period. For example, in 2006 when the PTC was extended for two years, GE increased wind turbine sales and companies built new wind manufacturing plants in three different states. While the increased manufacturing was in response to a short-term extension, it was done immediately following passage of the bill, indicating that companies were reacting to the potential for two years of increased demand. If demand for wind technology were incentivized over a ten-year period, domestic companies would likely emulate the 2006 trend and re-invest in the domestic wind infrastructure. The Berkley study suggests that a ten-year PTC extension would increase the domestic manufacturing share from 30%, to an astounding 70%. This increase would greatly decrease dependence on foreign manufacturing, while boosting the domestic economy, specifically in the local economies home to manufacturing plants. The third benefit is that a longer-term PTC would encourage private R&D. A ten-year PTC would encourage companies to improve technology as they increase long-term investment. Because a firm would be committed to make investments for longer than a 1–2 year period, it would have an incentive to make their technology less expensive and more efficient. It would have a guaranteed ten-year window to improve technology, rather than only a guaranteed shortterm window. The fourth benefit is the significant potential for reduced installation costs. While the cost for producing wind energy has been rising, a ten-year extension would reverse this trend. A tenyear extension of the PTC would decrease installation cost by about 15 percent. [sour ce – how calculated?] It is difficult to determine the exact reduction in cost a longer-term PTC would lead to, but it can be estimated that a five-year extension would decrease cost by about 8 percent, while a ten-year extension could decrease cost by about 15 percent. This would be caused by an aggregate of benefits—namely improvements in wind technology through R&D, increased domestic manufacturing, and reductions in project development and financing costs that are currently driven by rushed development schedules. The result would be savings passed onto the consumer due to the decreased cost of production. While a ten-year extension would increase credit claims by companies and require the Federal government to spend billions of dollars in the form of direct subsidies, it is possible that the overall cost to the government would be zero. Increased investment would also lead to increased tax liabilities as companies would increase expenditures and produce higher income. This would also boost certain industries and local economies, also creating greater tax liability. It is also possible that increased tax liabilities would not completely cover the cost of a long-term credit. A potential response to this problem would be to limit the subsidies available to traditional fuel sources. Coal producers enjoy over $14 billion a year in tax credits. [source – what kinds of subsidies?] Decreasing these subsidies would allow for the Federal government to make the credit revenue neutral, while also making wind more competitive with coal. VIII. Can the PTC Stand Alone? Cost is not the only reason wind power only accounts for only 1 percent of the total electricity generated in the United States. The lack of a transmission infrastructure has prevented companies from engaging in wind projects that would provide power to consumers in distant locations. Electricity produced from wind energy is not fully integrated in the U.S. transmission grid, allowing wind energy to only reach customers in a proximate geographic location. Wind sources are often far from large demand centers, making it impossible for the energy produced to reach these costumers. It is often too expensive for companies to build transmission lines to the large demand centers, where the energy would be available to a large number of consumers. However, investment into the transmission infrastructure of wind energy can solve this problem by allowing wind energy to be used by consumers far removed from the wind sources. Without the ability to reach a large number of consumers, companies have been reluctant to invest in expensive wind projects. However, with investment and integration into transmission infrastructure, wind power would be a far more attractive investment to energy companies. The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that that constructing about 12,000 miles of new transmission lines, at a cost of $20 billion, coupled with the PT, would allow wind energy to account for 20 percent of the electricity generation in the United States by 2030. This improvement in the wind energy transmission grid is technically feasible, as long as states and FERC are able to reach joint agreements allocating costs. With increased production of wind energy, state and Federal governments and agencies would be more willing to invest in transmission, as they would face pressure not only from wind producers, but also customers that desire a cleaner, cheaper, source of energy. Without a commitment to improving transmission infrastructure, it is likely that the use of wind power will plateau well below the 20 percent desired by the DOE. IX. Conclusion With the supply of traditional sources of energy disappearing and threat of global climate change looming, it is imperative that the U.S. moves towards a greener, more renewable source of energy. Wind energy offers the most effective way to move towards this goal. However, without a PTC that offers market certainty for a period longer than 1–2 years, wind energy will not be able to reach its full potential. If the government creates market stability with a longerterm PTC, and commits to improving the nation’s transmission infrastructure, the US should be able to transition to a cleaner, greener, and renewable way of life.