Auvai

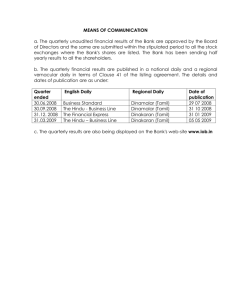

advertisement

Auvaiyar (Auvaiyár) Long before the modern world came to recognize the moral and mental worth of women, some ancient cultures gave the highest respect for womanhood by personifying wisdom and knowledge as a she. Thus, Sarasvati is the goddesses of Wisdom in the Hindu world, as Athena and Minerva were in Greece and Rome, and Isis was in ancient Egypt. There were also women mathematicians, thinkers and women in the ancient world. Hypatia in Alexandria was a mathematician, Lopamudra contributed to the Rig Veda, and Auvaiyar was a poetess in the Tamil world. The Tamil people recall with respect and affection this woman of extraordinary genius and keen intelligence who had the gift for encapsulating wit and wisdom in pithy sayings, verbal vitamins as it were that jolt us to awareness and direct us to enlightened values. Nowhere is the Shakespearean phrase "brevity is the soul of wit (wisdom)" more tellingly exemplified than in Auvai. Her alphabetically arranged maxims are both descriptive and prescriptive, and often within grasp of even young minds. Over the centuries millions of children in the Tamil world have read, learnt, and recited her immortal Átti Cúdi (aatti-chooDi), an alphabetically arranged series of simple didactic aphorisms: First the vowels, then the consonants of Tamil. Átti is the name of a flower, favored by Lord Genesha. ChooDi means one who wears. Thus the work is dedicated to Lord Ganesha. But the contents go beyond race and religion, creed and culture. A companion work she wrote is another mound of maxims. It is called Konrai Véndan: each maxim here is a string of four terse words. Konrai is the name of another flower associated with Lord Shiva. Véndan means king. This work is thus dedicated to Lord Shiva. It begins with: annaiyum pitávum munnaRi deivam: Mother and father are the first Gods to be reckoned. The genius of the Tamil language sparkles in these precious nuggets in rhythmic meters. These two works of Auvaiyar have acquired extraordinary prestige in Tamil culture. During many centuries when writing on palm leaves was in vogue, children began their education by reciting and writing the maxims of Auvaiyar, even as passages from scriptures are learned by rote in some other cultures. Auvai's precepts are nondenominational, though there is the customary invocation to the Almighty at the beginning. In the Auvai-inspired tradition, the letters of the alphabet introduce the young to values and wisdom, rather than to apples, boys, cats, and dogs. Auvai doesn't speak of átman, karma, devas, or mantra. Nor does she tell us how to achieve moksha. She is a down-to-earth mother of maxims, a teacher who utters wisdom as common sense and in simple language. She shows the path for balanced and meaningful living without the metaphysical mumbo-jumbo that is characteristic of more highly venerated Hindu writings. She was humble too. "What is learned has the measure of a fistful of sand, " she reflected, "what is not learned is vast as the world." This blessed lady was a child prodigy who talked poetically at the age of four. She grew up to be a lovely young woman, but when her father began to seek a beau to marry her off, she is said to have prayed to the Almighty to transform her into a wrinkled old grandma, white hair, curved spine and all, for wedded wifehood wasn't her goal in life. The boon was granted, so says the legend, and the dainty damsel was metamorphosed into an aged lady right away, and she became the doyenne of Tamil poetry. What a contrast from the normal obsession of many of the fairer sex to look younger than what the calendar reveals. So no one knows how Auvai looked as a damsel, for artists have always sketched her as a grandmotherly matron: indeed, that is what the name Auvai actually signifies. This is how she is sculpted on a pedestal in Chennai’s Marina beach, standing tall with a staff in one hand and a sheaf of writings on the other. Auvai was not a saint in the religious sense of the world, but she has been regarded as such in the Tamil world. She is perhaps the only secular poetess who has been enshrined in temples. She richly deserves to be venerated in temples, not only for having enriched her language with verbal gems, but also because those who enlighten the world through wisdom are truly divine. There is also more confusion than clarity regarding the name of Auvaiyar. Books on Tamil literature tell us that there were at least two Auvaiyars, perhaps three. The one we are talking about here is reported to have been the poet Tiruvalluvar's sister. Nobody knows for sure when she lived: between the first and the second century of the Common Era is what some scholars say. She had many royal patrons. She traveled places. As is not unusual when it comes to ancient history, many legends are associated with the name of this great personage, one of which is the Murugan once came to play with her. Or again, once she was told by a priest not to sit in a temple with her legs pointing in the direction of the icon of the deity, a not uncommon matronly posture in the Tamil world. Auvaiyar promptly asked the man to please show her a direction which pointed to a place where the Almighty wasn't present. The man realized he was confusing the icon for the Divine. Auvaiyar stands tall among the women-poetesses of the world, though she is hardly known beyond the Tamil-speaking people, even within India. As with all great writers, only those who have read her works can know her real greatness. She was the closest to Sarasvati in flesh and blood. Áttichúdi, simple as it is in enunciation, is in archaic Tamil. Not as undecipherable as Chaucer to modern English speakers, yet not readily understandable to many modern Tamil. So I am presenting this work to the reader with word by word meanings of the terse lines. It is my hope this will add to the interest in this masterpiece of world literature. Acharya Vidyasagar V. V. Raman Ames, IA March 10, 2013