Cultural Memory, Constructs of History and Moments of Being

advertisement

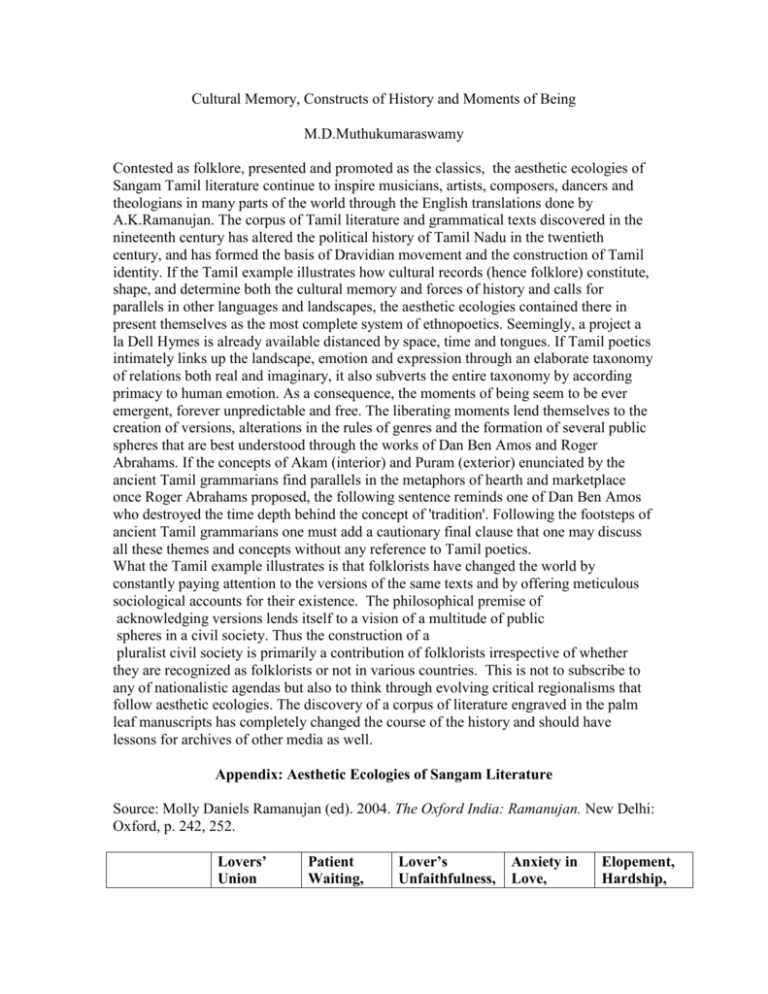

Cultural Memory, Constructs of History and Moments of Being M.D.Muthukumaraswamy Contested as folklore, presented and promoted as the classics, the aesthetic ecologies of Sangam Tamil literature continue to inspire musicians, artists, composers, dancers and theologians in many parts of the world through the English translations done by A.K.Ramanujan. The corpus of Tamil literature and grammatical texts discovered in the nineteenth century has altered the political history of Tamil Nadu in the twentieth century, and has formed the basis of Dravidian movement and the construction of Tamil identity. If the Tamil example illustrates how cultural records (hence folklore) constitute, shape, and determine both the cultural memory and forces of history and calls for parallels in other languages and landscapes, the aesthetic ecologies contained there in present themselves as the most complete system of ethnopoetics. Seemingly, a project a la Dell Hymes is already available distanced by space, time and tongues. If Tamil poetics intimately links up the landscape, emotion and expression through an elaborate taxonomy of relations both real and imaginary, it also subverts the entire taxonomy by according primacy to human emotion. As a consequence, the moments of being seem to be ever emergent, forever unpredictable and free. The liberating moments lend themselves to the creation of versions, alterations in the rules of genres and the formation of several public spheres that are best understood through the works of Dan Ben Amos and Roger Abrahams. If the concepts of Akam (interior) and Puram (exterior) enunciated by the ancient Tamil grammarians find parallels in the metaphors of hearth and marketplace once Roger Abrahams proposed, the following sentence reminds one of Dan Ben Amos who destroyed the time depth behind the concept of 'tradition'. Following the footsteps of ancient Tamil grammarians one must add a cautionary final clause that one may discuss all these themes and concepts without any reference to Tamil poetics. What the Tamil example illustrates is that folklorists have changed the world by constantly paying attention to the versions of the same texts and by offering meticulous sociological accounts for their existence. The philosophical premise of acknowledging versions lends itself to a vision of a multitude of public spheres in a civil society. Thus the construction of a pluralist civil society is primarily a contribution of folklorists irrespective of whether they are recognized as folklorists or not in various countries. This is not to subscribe to any of nationalistic agendas but also to think through evolving critical regionalisms that follow aesthetic ecologies. The discovery of a corpus of literature engraved in the palm leaf manuscripts has completely changed the course of the history and should have lessons for archives of other media as well. Appendix: Aesthetic Ecologies of Sangam Literature Source: Molly Daniels Ramanujan (ed). 2004. The Oxford India: Ramanujan. New Delhi: Oxford, p. 242, 252. Lovers’ Union Patient Waiting, Lover’s Unfaithfulness, Anxiety in Love, Elopement, Hardship, Domesticity “Sulking Scenes” Separation Separation from Lover or Parents palai (desert tree) Characteristic flower (name of region and poetic genre) Landscape kurinci mullai (jasmine) marutam (queen’sflower) neytal (blue lily) mountains Forest, pasture countryside, agricultural lowland Seashore Time Season night, cool season season of morning dew peacock, parrot monkey, elephant, horse, bull Late evening Rainy season morning All seasons Nightfall All seasons Sparrow, Jungle hen Deer stork, heron Seagull dove, eagle buffalo, fresh water fish Crocodile Shark jackfruit, bamboo, venkai (kino) waterfall waterfall Konrai (cassia) mango Punnai (laurel) fatigued elephant, tiger, or wolf, lizard omai (toothbrush tree) cactus Rivers pool Wells hill tribes, guarding millet harvest, gathering honey Plowman pastoral occupations selling fish and salt, fisherfolk Bird Beast (including fish, reptile, etc.) Tree or plant Water Occupation or people wasteland (mountain or forest parched by summer) midday season of evening dew, summer waterless wells, stagnant water wayfarers, bandits “This is not an exhaustive list, only a few of the elements that appear frequently in the poems are given here. The Tamil names of gods, heroes, clans, musical instruments, and kinds of food have been omitted.” (A.K.Ramanujan’s comment) The chart first appeared in The Interior Landscape (Ramanujan 1967). For a more complete table, see Singaravelu (1966:22), or Zvelebil (1973:100). Puram/Akam (Exterior and interior)Correspondences Akam Situation/Theme Puram kurinci, a mountain flower mullai, jasmine First union vetci,scarlet ixora Separation (patience) vanci, a creeper 3. marutam, queen’s flower Infidelity (conflict) ulinai, a cotton shrub 4. neytal, water lily Separation (anxiety) tumpai, white dead nettle 5. palai, desert tree vatai, sirissa tree 6. peruntinai,* “major type” Elopement, search for wealth, fame, etc. Mismatched love 7. kaikilai* “base relation” Unrequited love patan,* “praise” 1. 2. Not a name of a tree or a flower kanci, portia tree Situation/Theme Common Features cattle-lifting, night, prelude to war hillside; clandestine preparation for forest, rainy war, invasion season; separation from loved ones seige fertile area (city, etc.), dawn; refusing entry battle seashore, open battleground, no season; evening; grief ideals of no particular achievement, landscape; victory praise Struggle for excellence; endurance elegy, praise for heroes, asking for gifts, invective no particular landscape; struggle no particular landscape; a one-sided relationship