Dialogues

advertisement

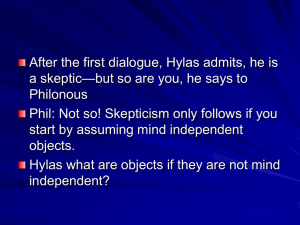

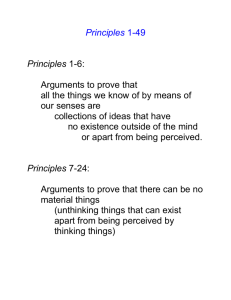

Hylas’s Accusations Philonous “professes an entire ignorance of all things [and] advances such notions as are repugnant to plain and commonly received principles.” (p.8) Philonous maintains “the most extravagant opinion that ever entered into the mind of man, to wit, that there is no such thing as material substance in the world.” (p.8) Philonous “denies the reality and truth of things.” Specifically, he “distrusts the senses, denies the real existence of sensible things, and pretends to know nothing of them.” (pp.9-10) Philonous’s Project Show that Hylas’s belief in the existence of external, independently existing bodies drives Hylas into scepticism and paradox while Philonous’s view that all that exists is minds and their ideas is actually consistent with commonly received principles Hence, that it is Hylas’s view that actually deserves to be considered extravagant. Philonous is the one who is in a position to affirm the existence of sensible things (ideas) while it is Hylas who is forced to confess that he knows nothing of the sensible things (externally and independently existing bodies) he believes in. A preliminary point Someone who denies the existence of body* is not on that account to be considered a sceptic. (Berkeley does not just think that the existence of body* is not provable. He thinks there can be no such thing.) * Here “body” means something considered to exist outside of all minds and independently of being perceived. Berkeley does not deny the existence of “body” considered as sensible things. Philonous’s Opening Move What is a sensible thing? Hylas’s Reply A thing that is immediately perceived by the senses. So a colour, sound, thing that is hot or heavy. Not the cause of these things. (Hylas starts off expressing a commitment to “naive realism”) Consequences Sensible things are nothing other than the sensible qualities or combinations of sensible qualities: light, colours, figures, sounds, tastes, smell, and tangible qualities. So if you take away all sensible qualities no sensible thing remains. Philonous’s Thesis (esse est percipi) A sensible thing can only exist insofar as it is perceived. Arguments for “esse est percipi” Identification of sensible objects with pains and pleasures Pain and pleasure are states of sentient beings. They do not exist apart from being perceived or outside of minds. But a very great degree of heat just is a form of pain, … … a more moderate degree just is a form of pleasure, … a yet less degree is a lesser pleasure, … … and an insensible degree is insensible This same identification holds for smells, and tastes, which are all either pleasant or unpleasant and so forms of pleasure & pain. Arguments for “esse est percipi,” cont.’d Perceptual relativity No object can have contrary states at the same time. But the same object can be felt to be both hot and cold at the same time. (The same holds for tastes, smells, colours, and magnitudes) So these qualities must be states of the percipient rather than of some independently existing object. Arguments for “esse est percipi,” cont.’d Causal parity (an “ad hominem” argument that might otherwise appear to be inconsistent with Berkeley’s principles) No one thinks that the sensation caused by a pin dividing the flesh is in the pin. By parity of example, no one should think that the sensation caused by an object affecting a sense organ is in the object. e.g., sound sensations and undulations in the air e.g., sensations of colour and waves or particles of light An objection Sensible qualities may be considered in two ways: as they are perceived by us as they are in bodies As they are perceived by us, they are degrees of pleasure or pain. But as they are in bodies they are not. Reply Sensible things are things immediately perceived by the senses, not the causes of those immediate perceptions. Moreover, there is no resemblance between the sensible qualities and their supposed causes. So sound causes cannot be acute or grave, loud or soft; colour causes cannot be bright or dark, red or green. And sound causes, being shapes (waves) are not the sort of things that can be heard, but only the sort of things that can be felt or seen. While colour causes turn out to be invisible motions and figures rather than anything that we actually see. Insisting that these things are “sounds” or “colours” brings us into conflict with common sense. A further objection Even if we grant that some sensible qualities (the “secondary”) only exist in us and only exist when they are perceived, there are other, “primary” qualities that exist in external, unthinking bodies. Problems with Primary Quality Realism Perceptual relativity arguments are as effectively employed against the mindindependent existence of the primary qualities as the secondary qualities. The primary qualities cannot be conceived to exist apart from the secondary. (So if the secondary qualities are granted to exist only in the mind and only when perceived, the primary must exist only in that way as well.) A Further Objection Though the act of perceiving may not exist outside of the mind, the object perceived by means of this act may exist outside the mind. Reply The mind can only be said to act insofar as there is volition involved. But in perception there is no volition. So the so-called “act” of perceiving turns out to be something that the mind does not do and so, on the account, it could exist outside of the mind (though this is absurd). Worse, the so-called “object” of perception could not possibly exist outside of the mind in many cases, e.g., the perception of pain. So the attempt to divide perception into an act that must exist in the mind from an object that must exist outside of it is incoherent. Yet another Objection Sensible things are all merely modes or qualities. But it is inconceivable how modes or qualities could exist on their own, without inhering in some material substratum or substance. Replies Substance and substratum are not sensible things. Neither can they be relative notions, implied by the existence of sensible things. Because we have no idea what we mean when we talk about these things. Neither could the group of sensible qualities mutually support one another. Because it has already been established that each sensible quality could not possibly exist outside of a mind (whether combined with others or not). Berkeley’s “Master Argument” It is impossible to conceive of something existing unconceived. Because when you conceive of something existing unconceived you yourself conceive that thing. [or you conceive nothing at all, in which case you still don’t conceive anything existing unconceived] So, nothing can legitimately be supposed to exist apart from being conceived. (Maintaining that something does exist unconceived when you cannot even so much as conceive or imagine something to exist unconceived is unacceptable.) Another Objection We see things at a distance from us. So things must exist outside of us and hence independently of being perceived. Replies We perceive things as being at a distance from us in dreams, even though they are not outside us What we see at a distance looks different close up. So what we were seeing when at a distance cannot have been the (then) distant object but must have been something in us. Someone born blind and newly made to see would not perceive things as being at a distance Since distance is a line turned endwise to the eye, the length of the line (and hence the distance) cannot be perceived. It has been shown that colours do not exist outside of the mind, yet they appear as being at a distance. A further objection The ideas or sensible things we immediately perceive are pictures of external things, and we perceive the external things mediately by perceiving these ideas. Reply Before something can be seen as a picture of something else, you need to have some prior acquaintance with that other thing. But the question at hand is what sensory experience, memory or inference could give us that prior acquaintance and so put us in a position to legitimately suppose that there are material things resembling our perceptions. Hylas’s Last Resort The existence of external, independently existing bodies resembling our ideas is at least possible. Reply (The “Likeness Principle”) It is not, because nothing can be like an idea but another idea … e.g., nothing invisible can be like a colour, nothing inaudible like a sound … because nothing we find in our ideas can be conceived to be the sort of thing that could exist outside of a mind. Conclusion Hylas: Upon inquiry, I find it impossible for me to conceive or understand how anything but an idea can be like an idea. And it is most evident, that no idea can exist without the mind. Philonous: You are therefore by your principles forced to deny the reality of sensible things, since you made it to consist in an absolute existence exterior to the mind. That is to say, you are a downright sceptic. So I have gained my point, which was to show your principles led to scepticism.