Plato`s Theory of Knowledge and the Doctrine of the Forms

advertisement

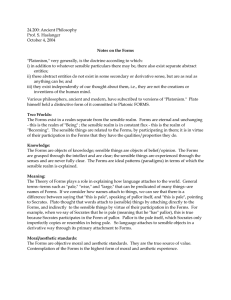

Plato’s Theory of Knowledge and the Doctrine of the Forms Socrates’ Heritage Ethical conduct must be founded on knowledge. Real knowledge must be knowledge of eternal values which are not subject to the impressions of the senses or subjective opinions but are the same for all people and all ages. Plato’s conviction: there can be knowledge in the sense of objective and universally valid knowledge. Main Arguments Knowledge is not Sense-Perception: the mind’s activity is necessary. Knowledge is not “True Judgment”: a judgment may be true without the fact of its truth involving knowledge on the part of the person who makes the judgment. Real knowledge: concern the universal, abiding, stable, unchangeable. To each true universal concept there corresponds an objective reality. Hierarchy of Knowledge The State of Mind Corresponding Objects noesis originals (arkhai) Episteme (Knowledge) dianoia mathematics Doxa (Opinion) pistis eikhasia zoa (real objects) eikhones (images) Theory of the Forms Forms or Ideas: universal, real, objective, unchanging essences. These Forms are the objects of true knowledge. Sensible things are copies or participations in these universal realities. One Form is central to the being and knowability of all the others: the Form of the Good (Republic 505a-509c). Hence the Theory of the Two Worlds: the Ideal World and the Sensible World. Significance Breaking away from the materialism of the preSocratics, asserting the existence of immaterial and invisible Being, a stable and abiding Reality. Agreeing with Heraclitus that sensible things are in a state of flux or becoming. They are not fully real, but they are not mere Non-being, as they have a share in being. Going beyond the interests of the Sophists and Socrates in ethical standards and definitions into the sphere of ontology.