Principles 1-50

advertisement

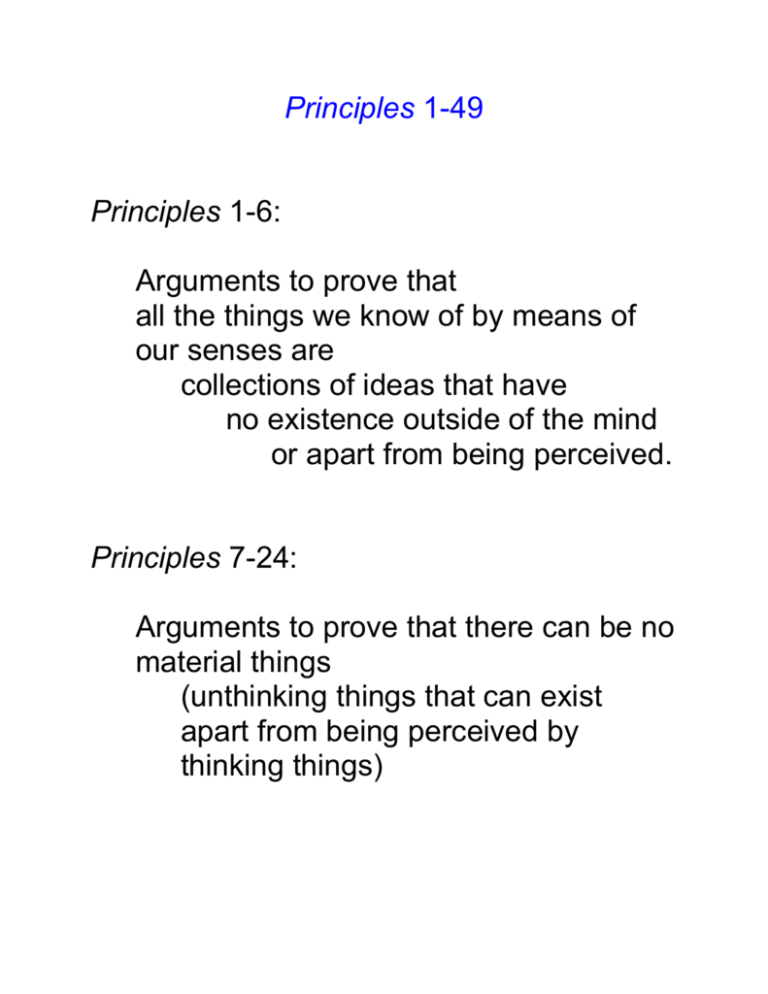

Principles 1-49 Principles 1-6: Arguments to prove that all the things we know of by means of our senses are collections of ideas that have no existence outside of the mind or apart from being perceived. Principles 7-24: Arguments to prove that there can be no material things (unthinking things that can exist apart from being perceived by thinking things) Principles 25-33: The distinction between real and unreal things and the nature of scientific knowledge. Principles 34-49: Replies to 6 objections. Principles 1-6 Principles 1-2: Survey of the objects of human knowledge. Principles 3: Analysis of what it means to say that a sensible thing exists. Conclusion: The things we know by means of the senses cannot exist apart from being perceived. Principles 4-6: Supplementary arguments in support of Principles 3. Principles 1-2 Sources of human knowledge (according to Principles 1, 18, 89) sense “inward feeling or reflection” memory & imagination reason What is known by sense, memory, & imagination: ideas What sensible things are: collections of ideas commonly observed to go together and so given one name. Is this true? Are (compound) things collections of ideas? Or collections of the things ideas are of? Phrases from Principles 1: “ideas of light and colours” “Other collections of ideas constitute a stone” Principles 49: “[extension and figure] are in the mind only as they are perceived by it, that is, not by way of mode or attribute, but only by way of idea; and it no more follows that the soul or mind is extended because extension exists in it alone, than it does that it is red or blue, because those colors are on all hands acknowledged to exist in it, and nowhere else.” Are ideas red or blue, extended and figured, or of red and blue, extension and figure? If the mind is not red or blue, extended or figured, and ideas are not red or blue, extended or figured, but sensible objects are red and blue, extended and figured, then how can sensible objects be collections of ideas, and how can it be said that they are in the mind? Dialogues III (p.82): “when I speak of objects as existing in the mind or imprinted on the senses; I would not be understood in the gross literal sense, as when bodies are said to exist in a place, or a seal to make an impression upon wax. My meaning is only that the mind comprehends or perceives them” Two ways of making sense of ideas Hume: ideas are literally coloured, extended and figured. There is no mind. There are just bundles of ideas. Reid: An idea is an act performed by the mind whereby the mind refers to an object that exists independently of that act. Berkeley seems to want to have it both ways. Another problematic phrase: “or else such as are perceived by attending to the passions and operations of the mind” (compare Principles 25) Solution (following Principles 89): “inward feeling or reflection” must supply us with “notions” rather than “ideas” and must be a distinct, non-sensory, form of intuitive knowledge restricted to self-consciousness This is the source of knowledge we rely upon in Principles 2. Principles 3 Q.: What does it mean for an idea to exist? A.: To be perceived by some mind. (or to be such that it would be perceived were some mind present) This is obvious for thoughts, passions and ideas formed by imagination. It is also all that we can mean when we speak of the existence of ideas imprinted on the senses, however complex. (See Dialogues I) But sensible things are nothing more than collections of ideas. So, sensible things cannot exist apart from being perceived. Principles 4-6 Arguments against the view that sensible objects exist apart from being perceived. Principles 4: The view is self-contradictory. Because sensible things are collections of ideas and ideas cannot exist apart from being perceived. Principles 5-6: The view requires an impossible abstraction Namely, of the being of a sensation, idea or impression on the sense from its being perceived. “It is impossible for me to see or feel anything without an actual sensation of that thing.” “My conceiving or imagining power does not extend beyond the possibility of real existence or perception.” “So it is impossible for me to conceive … any sensible thing … distinct from the sensation or perception of it.” Principles 7-24 Arguments against the existence of matter Principles 7-15: There is no known quality that could be ascribed to matter. Principles 8: The “likeness principle.” Principles 16-17: There is no meaningful way matter can be described. Principles 18-20: There is no reason for supposing that matter exists. Principles 21: Supposing that matter does exist leads to scepticism and irreligion. Principles 22-23: The master argument. Principles 24: The notion of matter is either self-contradictory or meaningless. Principles 7-15 There is no known quality that could be ascribed to matter. Principles 7 Matter could not have any of the sensible qualities. Because these are all ideas and no idea can exist in an unperceiving thing. Principles 8 Matter could not have any qualities that are like any of the sensible qualities Because these are all ideas and nothing can be like an idea but another idea. Principles 9-15 Matter could not have any of the primary qualities. Because the primary qualities are also sensible qualities and hence only ideas. Because the primary qualities could not exist apart from the secondary qualities, and the secondary qualities are granted by all to exist only in the mind. Because the same arguments (from perceptual relativity) that are used to prove that the secondary qualities exist only in the mind apply to the primary qualities (which are also relative to circumstances). Matter could specifically not be: Extended or mobile because the specific degrees of extension and mobility are relative to mental estimation and the notions of extension in general and motion in general are illegitimate abstractions. Compounded from a number of parts because unity and number depend on arbitrary decisions made by the mind. Principles 16-17 There is no meaningful way matter could be described. To say that it some substratum or support of unknown qualities is to employ metaphorical terms. Principles 18-20 There is no reason to suppose matter exists. Because it is not known by the senses, which only tell us about our ideas. And not inferred by reasoning from our ideas, considered as effects, to their causes. Because in dreams our ideas do not have material causes so there is no necessary connection between ideas and a material cause. Because no one understands how a material thing could affect a mind to give it ideas. Because a “brain in a vat” (actually, “an intelligence, without the help of external bodies”) has as much reason to suppose there are material objects as we do. Principles 22-23 The “master argument” “If you can but conceive it possible for … any one idea or anything like an idea, to exist otherwise than in a mind perceiving it, I shall readily give up the cause.” Note: Conceiving it possible involves more than conceiving an object without conceiving anyone standing in its vicinity perceiving it. It involves explaining what it is about the idea in question that would make it possible for it to exist apart from being perceived by a mind. No such explanation could ever be given because it is a “manifest repugnancy” for an idea to exist unperceived. Hume’s response to the master argument Each of our ideas is entirely complete in itself and so capable of existing on its own, apart from anything else. Principles 25-33 Reality. Principles 25: Ideas are inert. Principles 26: But they continually change. So there must be something or things that produce and change them. Principles 27: We cannot have any idea of the things that perceive and cause ideas, though we can form some “notion” of them by reasoning from their effects. (Principles 89: And by inward feeling or reflection.) Two Classes of Ideas. Sense produced Metaphysical independently of Difference my will Phenomenal strong, lively, and Difference distinct Phenomenological steady, ordered, Difference and coherent Imagination produced by my will weak, dim, and confused excited at random Ideas of sense are real things. Ideas of imagination are “ideas” in the proper sense or images of real things. Both ideas of sense and ideas of imagination only exist in our minds. Ideas of sense must be produced by some other, vastly superior, wise and benevolent spirit. The laws of nature are the rules this spirit invariably follows in exciting ideas in us. We mistakenly suppose that earlier ideas in a regular sequence cause those that come later. Principles 34-49 5 objections: 1. Berkeley’s theory absurdly denies the existence of a real world. 2. Berkeley’s theory absurdly rejects the distinction between reality and imagination. 3. Things must exist outside of the mind because we see them at a distance from us. 4. Berkeley’s theory absurdly entails that things are constantly popping in and out of existence. 5. If extension and figure exist only in the mind, then the mind must be extended and figured. 1. Principles 34-40 Berkeley’s theory turns the sun, moon, and stars; houses, mountains, trees and stones into mere chimeras and illusions. Ans.: Ideas that are imposed on your mind against your will are as real as you could want anything to be. And only philosophers and atheists look for anything more in reality. Berkeley’s theory denies the existence of all corporeal substances. Ans.: It does not deny the existence of what ordinary people mean by “corporeal substance”; it only denies the absurd notion of a mindindependent support of accidents and qualities. It is absurd to say we eat and drink ideas and are clothed with ideas. Ans.: This only sounds absurd because in common language “idea” is only used in the proper sense, not in the expanded philosophical sense. Proper sense: an image made by the imagination of a sensible object. Philosophical sense: whatsoever is the object of the mind in thinking. As a matter of fact, we eat sensible things and are clothed with sensible things, and sensible things are collections of ideas in the expanded sense. So we do eat and drink ideas and we are clothed with ideas. Berkeley’s theory is contrary to what our senses tell us. Ans.: The belief that things continue to exist when not being sensed goes well beyond anything the senses could possibly tell us. 2. Principles 41 Berkeley ignores the distinction between real things and illusions. Ans.: (additional to what has already been said on this topic) The distinction between reality and illusion has nothing to do with the distinction between what exists inside the mind and what exists independently of the mind, as is proven by the case of the distinction between real pain and imagined pain. 3. Principles 42-44 Berkeley’s theory is inconsistent with the fact that we see things existing outside of the mind, since what we see is at a distance from us. Ans. 1: Objects seen in dreams appear to be outside of us, yet they are not. Ans. 2: Outwardness is not immediately seen, but is rather inferred from signs in what is seen, as explained in the New Theory of Vision. Remark 1: These signs are nothing like the objects they signify. Remark 2: The objects signified by the signs are not in fact external objects. They are actually just collections of tangible ideas that we anticipate we would experience if we were to perform certain acts of will that are regularly followed by those collections of ideas that we call motions of our bodies. 4. Principles 45-48 It is absurd to imagine that things are constantly popping into and out of existence. Ans. 1: The absurdity is rather in supposing that an idea or a collection of ideas should exist unperceived. Ans. 2: In presenting this supposed absurdity, I am saying nothing more than is accepted by those philosophers who accept the doctrine of constant creation, which is well founded in meditations on the nature of time. (What is past no longer exists, so the mere passage of time is sufficient to annihilate the universe from moment to moment, necessitating its constant recreation if it is to be preserved in existence) Ans. 3: In addition to the reasons already given for this conclusion, it follows from the doctrine of infinite divisibility that whatever it is that is supposed to exist unperceived could have none of the qualities we learn of through our senses. Ans. 4: Bodies that are unperceived by us may still continue to exist as long as they are perceived by some other spirit. But would these bodies perceived by others be the same ones I perceive? How could a collection of ideas in my mind be identified with a collection of ideas in some other mind so as to constitute the same body? 5. Principles 49 If extension and figure exist only in the mind, then the mind must be extended and figured. Ans.: Extension and figure exist in the mind “by way of idea” rather than “by way of mode or attribute.” Remark: Existing in the mind “by way of idea” is in fact the only way extension and figure could exist since the notion of existing “by way of mode or attribute” involves the meaningless notion of a substance. What does it mean for extension and figure to exist in the mind “by way of idea?” Is the idea is an image of extension and figure (hence something extended and figured?) If so, then since what is extended and figured must be in some place and the mind is not supposed to be extended and figured it follows that ideas must exist somewhere outside of the mind contrary to what Berkeley has maintained If the idea is not an image then Berkeley’s argument against abstract ideas loses much of its force. And we have to wonder what else it would be. Whatever it is, since the object the idea is of is extended and figured, it must be in some place, and if the idea is not extended and figured the object must exist outside of it contrary to what Berkeley maintains.