crime and punishment revision notes 1

advertisement

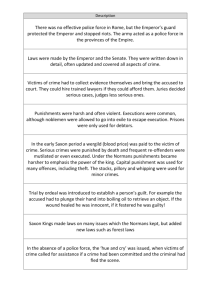

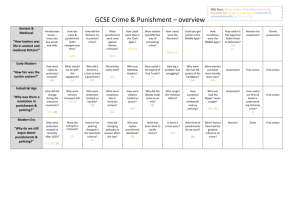

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT REVISION NOTES 1 Key ideas Ideas of what ‘crime’ is have changed over time. Causes of crime have been different in different time periods. Ideas of punishment have changed over time. Policing has changed over time. Different people have different experiences of the law. Different people have different ideas about crime and punishment. Change sometimes happens because of important people. Change sometimes happens because of the way society is changing. These causes are linked. 1450-1750 Crime and punishment at the end of the Middle Ages (Medieval period) about 1450 Rich people were in power. They wanted to protect money and property. Stealing was seen as just as bad as murder and rape. Most people could not vote so they could not change things. Royal Courts dealt with serious crimes. The punishment for murder, rape and stealing was death by hanging. Anyone aged over 10 could be hanged. The punishment for cheating, breaking agreements or assault was a fine of money. Another punishment was being forced to leave the country (outlawed). Manor Courts dealt with less serious crimes. The main punishment was fines. Prisons were not used as a punishment. They were just places to hold people waiting for trial. 1 The crime rate went up and down. Reasons for the crime rate going up: Rising prices Rising unemployment War Weak government Corrupt judges Reasons for the crime rate going down: Cheap food Plenty of jobs Peace Strong government Honest judges There were no police, so…. How did the authorities try to prevent crime? Making groups of people responsible for each other’s actions Tithing – every freeman belonged to a group of 10 men Hue and cry – everyone had to hunt for the criminal Scaring (deterring) people by the threat of punishment Church teaching about right and wrong How did they try to catch criminals? It was up to ordinary people to catch criminals Getting local people to decide if the person they knew was likely to commit a crime How did they decide if someone was guilty or innocent? Witness of neighbours Trial by jury It was therefore very difficult to find out who had committed a crime. 2 Vagrants, vagabonds and beggars In the late 14th and 15th century many people wandered from town to town looking for work. Why? Problems in the cloth industry Large numbers of people with no jobs Prices going up faster than wages Monasteries closed down (they had supported poor people) End of wars in England so lots of soldiers with no work Growing population – more people wanting jobs and food No system to help the poor and sick Begging was treated as a crime and harshly punished. Why? People felt threatened by the large numbers of beggars on the streets Communities did not like having to pay for the beggars that turned up in their areas Acts of charity were not enough to help all the poor people Poor people were more likely to turn to stealing How were they treated? Some places gave special badges to sick or disabled beggars (‘the deserving poor’) and allowed them to beg. Others (‘study beggars’) were seen as lazy and punished. Some sturdy beggars made themselves disabled to get the badges. 1494 Vagrancy Act - vagabonds and beggars could be put in the stocks and forced to leave the town. 1547 Vagrancy Act - beggars were forced to work. They had to be whipped and branded. This law was later changed because it was too strict. 1572 prisons (houses of correction’) were built to keep beggars The number of beggars grew because of changes in society. Healthy beggars were treated as criminals. It was impossible to stop people begging because they were poor as a result of wider causes. 3 CRIME AND PUNISHMENT REVISION NOTES 2 Traitors and treason Treason = rebelling against the king. Between 1485 and 1745 there were many rebellions against the kings and queens. The idea was that kings got their power from God (divine right), so treason was against God as well as the king. The Gunpowder Plot On 5th November 1605 a group of Catholics tried to blow up King James I in Parliament. Their punishment was to be hanged, drawn and quartered. Hanged by the neck, cut down when still alive and then cut open. Body divided into 4 quarters. This punishment of mutilation lasted until 1870, for anyone who tried to overthrow the king or queen. Punishment was so harsh because the people in power were afraid of rebellion. Rulers and ruled Early 16th century: many changes led to crimes. Growing towns led to street robbers (footpads) in dark alleys. Changes in religious belief led to people refusing to follow official religion. Increased unemployment led to beggars wandering from town to town. Better roads led to highwaymen robbing travellers. Rich people made the laws to protect their property from the poor. Rich people had power over poor people. Men had power over women. Adults had power over children. But the population was growing fast. Big towns were harder to control. 4 Poaching Before, land had been common and shared. Now rich people were buying and enclosing common land. In the past ordinary people had the right to hunt animals like rabbits. Now there was a law against poaching. Poachers sometimes worked in gangs. Main punishments Humiliation – stocks or pillory Fines – paying money Execution – hanging (for ordinary people) or beheading (for rich people) If a woman killed her husband she was strangled and burnt. The idea? Retribution (punishment) and Deterrence (preventing crime) The ‘Bloody Code’ This was the system of punishment that had death as the punishment even for small crimes. In 1688 50 crimes were punished by death; by 1815 death was the punishment for 225 crimes. Stealing sheep, damaging trees and stealing rabbits all had the death penalty. One famous criminal was Jack Shepherd, a thief who made very clever escapes from prison. When he was hanged, 250,000 people were in the streets to cheer him as a hero. Hangings were at Tyburn just outside London. Preventing crime No police force. Constables and watchmen. Thieftakers. The most famous thieftaker was Jonathan Wild. He pretended to catch thieves. In fact he was a criminal in charge of a gang of thieves. He was hanged in 1725. 5 CRIME AND PUNISHMENT REVISION NOTES 3 1750-1900 Crime and punishment at the time of the Industrial Revolution Changing society Britain was changing because of growing industry. Huge growth in sizes of towns and cities led to Extreme poverty More street crime and burglary Alcoholism and riots More chances for crime with rich and poor living close together Prostitution (including children) Immigrants moving into areas of poverty, many turning to crime to survive In the cities it was harder to know and keep track of people Dealing with protest and unrest Poor living and working conditions. Many workers desperately wanted change. They saw the Revolution in France (1789) and hoped for the same thing in Britain. Some of the people’s demands: The right to vote The right to strike The right to criticise the government No police force, so the government used soldiers against the people. They also used law against people who protested. 1817 a new law said prisoners could be held without trial 1819 soldiers attacked a peaceful protest in Manchester – 18 people killed and 500 injured. This was known as the ‘Peterloo Massacre’. So the government passed strict laws: No training with weapons except for soldiers No public meetings unless the government agreed Heavy punishment for criticising the government 6 The Tolpuddle Martyrs 1833 peaceful farm workers formed a trade union to stop their wages going down. It was against the law to swear a secret oath. Rich farmers and the government used this against the farm workers. They were arrested and transported to Australia for 7 years. Big protests led to their release in 1836. Later in the 19th century governments improved conditions for poor people. As a result there were less protests. Smugglers The government put up taxes on tea and alcohol. So gangs of smugglers made money from illegal trade. The Hawkhurst gang was very well organised and very violent. There was huge demand for smuggled goods. Taxes went up to pay for the war against France. This led to more smuggling. Many ordinary people supported the smugglers. Many people living near the coast helped the smugglers. Smugglers were punished very harshly. This made people see them as heroes. When the government reduced the tax in the 1840s, smuggling ended. Police. Policing before 1829: Watchmen who kept an eye on property Part-time soldiers to put down riots Constables who dealt with minor crimes and beggars Bow Street Runners, a small private force in London A few horse patrols in London to deal with highwaymen The first government run police force was set up by Sir Robert Peel (the Home Secretary) in 1829. This was the Metropolitan Police in London Peel was careful to make the police look different from the army. Their main job was to deter people from being criminals. In the next few years other cities set up police forces. At first the police were not popular but this slowly changed during the 19th century. Police pay and training got better. Police became better at catching criminals. In 1842 the first detectives began work in London. Their job was to solve crimes. The detective department was later called the CID. Police began to use photos of suspects to help them catch criminals. 7 CRIME AND PUNISHMENT REVISION NOTES 4 New ways of dealing with crime in the 19th century The end of the ‘Bloody Code’ By the start of the 19th century the ‘Bloody Code’ was not working. Although the punishment for most crimes was death, the number of criminals actually being hung was small. The crime rate was going up. Reasons why the ‘Bloody Code’ was failing: People on juries often refused to find a person guilty if the punishment was death. Public executions did not scare most people: people found them entertaining. Crime was caused by growing population, poverty and industrialisation. It was also a time when the authorities did not have wide support from the people. Most people could not vote Times were hard There were many protests against the government. In 1823 Robert Peel reduced the number of crimes punishable by death. In 1869 public executions were banned. New punishments (a) Transportation. Convicts were sent to America and the Caribbean to work on plantations. In 1776 America won its independence so Britain could no longer transport convicts there. After 1776 criminals were transported to Australia by ship. Reasons for transportation Prisons and prison ships (hulks) were overcrowded and diseased The government wanted to get rid of criminals They thought the idea of being sent so far away would scare people from committing crimes They wanted to stop the rise in crime in the cities They wanted to get rid of protesters against the government They wanted free workers to build up Australia They wanted to stop enemies like France getting hold of Australia 8 Most transported convicts were small thieves and petty criminals. Over 16,000 people were transported to Australia. A prison hulk Transportation ended in 1868. Australia did not need forced workers any more. Criminals could be dealt with in the new improved prison system. Many people were against transportation, saying it was too expensive. Some people thought transportation did not work because it gave criminals a new better life so it did not deter (scare) people. Other people thought it was too harsh and cruel a punishment for small crimes. (b) Prison reform Before the 19th century prison was not usually a punishment. It was used to hold people before they were executed or transported. It was also used to hold people who owed money. Prisons were privately run as a business. For poor people conditions were very bad: overcrowding, disease and violence. Richer people could pay for better conditions. Thinking about prisons began to change. Some reasons for prisons: Retribution – to punish people for doing wrong Deterrence – to put other people off doing crimes Removal – to keep criminals away from everyone else Rehabilitation – to change people for the better Restitution – to make criminals do work to pay back to society Newgate Prison in the 18th century. 9 Prison reformers John Howard He was High Sheriff of Bedfordshire and was shocked by conditions in the prison He travelled round Britain and Europe looking for better ideas for running prisons. His 1777 report on prisons called for Decent food Useful work Christian teaching Visits by doctors Elizabeth Fry She was a Quaker and very religious. She visited women in Newgate Prison, London. She found women and children mixed with men and suffering extreme violence and disease. She set up education classes for women She got prisoners to vote for rules to improve their conditions Her 1825 book called for changes to prisons, especially for women and children. Sir Robert Peel He was Home Secretary in the government. He got Parliament to pass a law – The Gaols Act 1823 – to set up a proper system of prisons run by the government. Useful work for prisoners so they could learn a trade Separate accommodation for women with female prison officers Proper inspections of prisons Uniforms Visits by doctors and chaplains Basic education Clean, separate cells Many new prisons were built. The first was Pentonville in London Howard and Fry had wanted rehabilitation and reform. But many in the government wanted retribution and deterrence. So the system in the new prisons was harsh: Strict rules and uniforms Pointless work: the crank, the treadwheel and picking oakum The Separate System and the Silent System which led many to kill themselves. The 1820s were a time of great change in dealing with crime. When Sir Robert Peel was Home Secretary the Bloody Code was ended, the first police force was set up and the new prison system was started. 10 CRIME AND PUNISHMENT REVISION NOTES 5 1900-2010 20th century changes in policing The impact of technology Fingerprinting since 1901 Police radios since 1910 The Police National Computer since 1980 The DNA National Database Library since 1995 Cars and motorbikes CCTV security cameras since the 1970s Speed cameras Community policing Neighbourhood Watch schemes involving local people Special units Anti-terrorist Squad Fraud Squad Transport police Drugs squad Training and recruitment National Police Training College from 1947 Weapons More armed police Riot gear Changing patterns of crime since 1900 The proportion of violent crime has gone down. Between the 1960s and the 1990s the crime rate went up. Since 1992 the crime rate has been going down. Why is this? Maybe because people have been generally better off Maybe because more criminals have been imprisoned However, not all crime is reported. Muggings, rapes, domestic violence and street crime are not always reported to the police. Burglary usually is reported because victims need to claim insurance. 11 But many people think the crime rate is going up. Why? Stories in the media Personal experiences of street crime and burglary Changing ideas of what is a crime Racist crime has become a bigger issue Conscientious objectors were treated as criminals because they refused to fight in the World Wars The law has changed to punish domestic violence New laws were made to cover traffic crime such as speeding, drink driving and use of phones while driving In 1993 the murder of Stephen Lawrence, a young black man, led to an inquiry which accused the police of ‘instututional racism’ when they did not do enough to catch the murderers and treated the family badly. New crimes or new versions of old crimes? International smuggling NEW – drugs (heroin, cocaine), cigarettes, DVDs OLD – alcohol, tobacco smuggling in the 18th century People trafficking NEW – women and children into prostitution; people into forced labour such as farm work, building, food processing and domestic slavery OLD – female and child prostitution in the 19th century Computer crime NEW – illegal images, illegal downloads, phishing, hacking, identity theft, money fraud and laundering OLD (before computers) – harassment, illegal images, fraud, impersonating another person Changing punishments in the 20th century Changes in prisons The Separate System was abolished Open Prisons for less dangerous criminals and those close to release High Security prisons Probation 1949 Criminal Justice Act abolished hard labour and beatings Detention Centres for young criminals 12 Women prisoners Women commit less crime than men 14 women’s prisons 4 units for young women 7 mother and baby units Young prisoners 1908 prisons called Borstals for young people separate from adults The UK locks up more children than other European countries Alternatives to prison Community sentences Drug or alcohol treatment centres Charity work Anti-social behaviour order (ASBO) Electronic tagging The abolition of the death penalty (capital punishment) 1908 1933 1950 1953 1955 1964 1965 1969 people under 16 no longer hanged people under 18 no longer hanged Timothy Evans hanged for the murder of his wife and baby. It was later found out that another man (Christie) had killed them and five other women. Derek Bentley hanged after his friend Chris Craig shot a policeman when they were doing a robbery. He had a mental age of 11. Craig was not hanged because he was under 18. Ruth Ellis was the last woman to be hanged. She killed her boyfriend who had violently abused her. The last executions Capital punishment for murder suspended for 5 years Capital punishment for murder abolished Arguments for keeping capital punishment: It prevents some murders and violent crime because criminals are scared of dying A murderer late released from prison can kill again Most police and people support the death penalty After a terrible murder, only execution of the murderer can give the victim’s loved ones relief and revenge. Life imprisonment is more cruel and much more expensive Arguments against capital punishment: Sometimes innocent people are hanged by mistake. It is wrong to kill: it is an uncivilised, barbaric punishment. The murder rate does not rise in countries without a death penalty. Juries are more likely to find murderers guilty of there is no death penalty. Most murders are not planned but happen on the spur of the moment. The fear of execution would not prevent these murders. 13 CHANGING VIEWS OF WHAT IS A CRIME CRIME AND PUNISHMENT REVISION NOTES 6 Changing views of what is a crime. Some activities were sometimes seen as a crime and sometimes not. The attitudes of ordinary people were different at different times. The actions of governments were different at different times. Why do ideas about crime change? Fear Events Public attitudes Organisations Government actions We are looking at three examples of this: Witch hunts in the 16th 17th centuries Conscientious objectors in the early 20th century Domestic violence in the late 20th century Are the beliefs that led to witch hunts a thing of the past or do these beliefs still exist? Is it justified to refuse to fight in a war? Is domestic violence still a problem or has it been ended? 14 CHANGING VIEWS OF WHAT IS A CRIME Witchcraft and witch hunts Before the 16th century In the Middle Ages people had been tried for witchcraft in Church courts. It was seen as an offence against the Church. Punishments were light. Most were ordinary women using herbs and charms to help poor people who could not afford doctors. Beliefs in magic from old religions still survived. Many people believed a witch met the Devil and the Devil sent them animals called familiars. Why were there so many witch hunts in the 16th and 17th centuries? Actions by the rulers In the 16th and 17th centuries kings and queens always feared plots and rebellions against their power. King Henry VIII in 1542 passed a law making witchcraft a serious crime punishable by death Queen Elizabeth I in 1563 passed a stronger law saying there were 2 kinds of witchcraft: Major witchcraft (trying to make someone die or raise the spirits of the dead) – punished by death. Minor witchcraft (using magic and charms) – punished by stocks or prison. King James I in 1604 passed an even stronger law. He believed in witches and feared them. He even wrote a book about them (Demonologie). Witch hunts began in a big way after the 1604 law. 15 Why were these laws passed? CHANGING VIEWS OF WHAT IS A CRIME Religion Conflict between Catholics and Protestants. Poverty Lower wages, less work and a wider gap between rich and poor. More beggars and vagabonds. Changes in society People moving away looking for work Families and communities breaking up Old women left on their own Civil wars in the 1640s When times were hard….. ……. rulers saw witchcraft as an offence against the government ……. people looked for someone to blame ……. there were more bad feelings between neighbours ……. people believed God was angry ……. People believed the Devil was at work Most accusations of witchcraft were made by richer people against poor people. Why were most accusations against women? 90% of accusations were against women between 1450 and 1750. Most were over 50 and lived alone. Many men feared or hated women (misogyny) Christianity portrayed women as weaker than men and more likely to do the Devil’s work (e.g. Adam and Eve) Puritans (extreme Protestants) believed women would tempt men to bad actions Some older women did abortions which was a crime punishable by death What evidence was used against ‘witches’? Strange marks on the body The needle test (if she did not feel the prick she was with the Devil) Evidence from neighbours ‘Possessed’ children acting as accusers Confessions (often after torture such as sleep deprivation) ‘Proof’ if two ‘witches’ swore that another person was also a witch The ‘swimming test’ 16 Witch hunts and punishments CHANGING VIEWS OF WHAT IS A CRIME The most common punishment was death by hanging. Between 400 and 1,000 people were hanged between 1542 and 1736. There were some times when attacks on ‘witches’ increased massively: for example, in the middle of the 16th century under Mary I and Elizabeth I – a time of religious change and conflict. The worst time was in East Anglia during the English Civil Wars 1642-1649. Matthew Hopkins, Witchfinder-General in Essex, accused 36 women and got 19 hanged; 9 more died in prison. Hopkins was paid for each execution. Why did the number of witchcraft trials go down? After the 1660s change slowed down and society was more peaceful. Many people started to be better off and relations between people in villages got better. More people stopped having superstitious beliefs and took a more scientific view of the world. Many things that had been seen as the work of evil spirits began to be explained by science. The last execution for witchcraft was in 1684. Witchcraft was still a crime until 1736 when all laws about witchcraft were abolished. 17 CHANGING VIEWS OF WHAT IS A CRIME Conscientious objectors (‘COs…Conchies’) What do you do if your beliefs tell you one thing and the law says another? “The government has been elected democratically. It passes laws for the good of all the people. Everyone should obey the law even if they don’t agree with it.” “But what if the law tells you to do something that goes against your deep beliefs? What if the law tells you to kill and you don’t agree with killing?” WHAT DO YOU THINK? Before the 20th century wars were fought by volunteers. If you didn’t agree with fighting you avoided joining up. Things were very different in the 20th century during two World Wars. Conscientious objectors = people who are against fighting in a war because of their deeply held beliefs. 3 main types of CO Religious Opposed to all war because of their religious belief. For example, Christian groups like the Quakers who follow the teaching in the Bible saying ‘Do not kill’ and the advice from Jesus to ‘turn the other cheek’ when someone attacks you. Moral Pacifists who are opposed to all war because they believe it is morally wrong. They believe war never solves problems: it just creates problems that lead to another war. Political Not against all war but they object to particular wars for particular reasons. Socialists and communists might refuse to fight in wars that are protecting big companies and making them rich. But in the 20th century refusing to fight became a crime. 18 CHANGING VIEWS OF WHAT IS A CRIME The First World War 1914-1918 This became a ‘total’ war involving the whole society. At first the army was made up of volunteers. But large numbers were killed. The Military Service Act 1916 introduced conscription: it said everyone aged 18 to 36 must fight. The Quakers objected to this. They organised meetings. Often police and members of the public broke up these meetings violently. They saw the COs as cowards and traitors. The new law had a ‘conscience clause’ allowing people not to fight if they proved it was against their deep, honest beliefs. COs had to explain their reasons to a military and other middle-class people. What the tribunal could decide: About 16,000 people refused to fight in the war because of their consciences. This made them very unpopular and they were often abused. tribunal, a court made up of army officers Absolute exemption. Allowed not to fight and to stay free. Usually only workers helping the war effort such as miners and farmers were excused. Conditional exemption. Free from war duties but sent to a work camp. Exemption from combatant duties. Free from fighting but helping in a war zone, maybe driving ambulances or carrying stretchers. Rejection. Very hard labour in prison and/or forced to go and fight with the threat of execution Only 400 COs were given absolute exemption. Alternativists refused to kill or hurt anyone but were willing to risk their lives in war zones helping in other ways. Several COs won medals for bravery. But many employers refused to give them work and they were sent to work camps to crush stones. Absolutists believed the war was so wrong that they refused to do anything to help the war. They were treated as criminals and sent to prison. Prison warders treated them very badly. Some were taken to France, forced into uniform and told to fight or they would be killed. 10 COs died in prison; 63 died shortly after release. 3 had mental breakdowns. After the war they were not allowed to vote for 5 years. Many could never get jobs; some were beaten up. 19 The Second World War 1939-1945 CHANGING VIEWS OF WHAT IS A CRIME Conscription came in at the very beginning of the war. But attitudes were different and COs had an easier time. The horrors of the First War had made many people agree with or understand pacifists. Warfare had changed and relied more on machines and technology. The war needed better trained soldiers and did not need so many men. Britain was fighting against Hitler’s Germany and most people believed they were fighting against evil: fighting for freedom and the right to choose. Many people felt that if Britain was fighting for freedom of conscience then conscientious objectors had to be accepted. Other people still saw COs as cowards and traitors, especially as the enemy was seen as evil. tribunals were different: no military officers and people from all classes. Over 59,000 people claimed exemption. 47.000 of these were given absolute or partial exemption. The Most of them cooperated with the authorities, working in factories or on the land. Some did dangerous jobs in the war zone, driving ambulances or doing bomb disposal. Absolutists joined the Peace Pledge Union who tried to encourage people not to fight. They refused to do any activity linked to the war. Usually they were not sent to prison. They were even allowed to put up posters. However, many ordinary people still saw them as cowards and traitors. Some were attacked or sacked from their jobs. But mostly they did not suffer as badly as in the First World War. Conscription in Britain finally ended in 1960. 20 CHANGING VIEWS OF WHAT IS A CRIME Domestic violence Physical abuse by a husband or male partner of a wife or female partner. (Now also seen to include verbal bullying, mental abuse, domestic violence in a gay/lesbian relationship or violence by women against men.) Before 1970. Although women had fought for and gained many equal rights, little had been done about domestic violence. Before the 20th century the law gave husbands and fathers the right to beat wives and children ‘in moderation’. A woman who killed her husband was guilty of ‘petty treason’, a more serious crime than murder. For a woman to murder her husband – even in self defence – was much more serious than a man murdering his wife. There was a general idea about the ‘rule of thumb’ – that a man could beat his wife with a stick as long as it was no thicker than his thumb. A judge in 1782 was believed to have said this. Women who suffered ‘severe violence’ could apply for a peace bond which meant the husband had to pay a fine. But only rich women could afford this. Laws did change slowly in the 19th century but little was done by the law to protect women. Sometimes men were punished by their local community. Really bad cases were sometimes reported in the papers. 21 Why was the government so slow to act? Most believed that the law should only apply to public life and not intrude into private life. Women had little political power and could not vote. All laws were made by men. The police force were all men and did not like getting involved in ‘domestic incidents’. Domestic violence was seen as part of a problem of working class drunkenness. Violence in middle and upper class homes was ignored. Women were often too scared to speak out and complain. Why did it become a ‘crime’ after 1970? Campaign groups Feminists and the Women’s Liberation Movement pressed for change. Marches and other protests were covered in the media. New ideas about the role of government People began to accept that the state could get involved in family life to improve the quality of life. This included child protection and health care. The NHS came into being in the middle of the 20th century. Power of the vote Women got the vote in 1918 and by 1928 had equal voting rights to men. Governments had to consider the needs of women to get elected. Media Newspaper, magazines, radio and television all covered more domestic violence stories. TV soaps such as Brookside in the 1990s (the Jordache family) and EastEnders in the 200s (Little Mo and Trevor) had domestic violence storylines. 22 Key moments 1971 the first women’s refuge, Chiswick Women’s Aid. Domestic violence raised for the first time in Parliament by Jack Ashley MP. Parliament set up a Select Committee on Violence in Marriage to look at the law. 1974 the National Women’s Aid Federation brought together all the refuge services across the UK and helped improve support for women and children, as well as pressing for a change in the law. There was a lot of pressure on the police to change its approach. Police chiefs resisted this, saying domestic violence was not as important as ‘more serious problems’. 1976 Domestic Violence Act Victims can get 2 kinds of protection: Non-molestation orders Exclusion orders, banning the abuser from the home 1991 rape within marriage classed as a crime 1996 Family Law Act gave extra protection to victims; in all cases of violence used or threatened the police must arrest. 2004 Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act. All victims, male and female, protected equally. More power to police and courts to act against abusers, including prison sentences for one who breaks a non-molestation order. Over 30% of domestic violence is against men but very few male victims come forward. 1 in 4 women are victims of domestic violence at some point in their lives. 1 in 6 men are victims of domestic violence at some point in their lives. 23