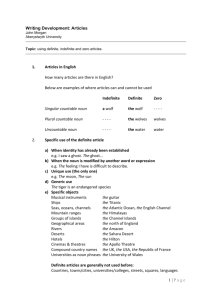

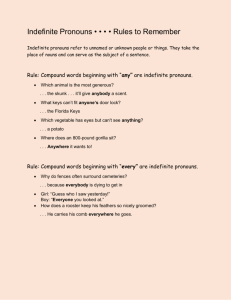

2.1 Referential Noun Phrases

advertisement