Department of PhilosophyPhilosophy 370A Problems in Analytic

advertisement

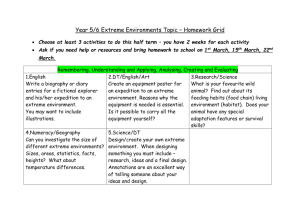

Department of PhilosophyPhilosophy 370A Problems in Analytic Philosophy Fall 2005 Topic for 2005: Philosophical Aspects of Fictional Discourse Instructor: Prof. David Davies Time: TTh 14:30-16:00 Room: Arts 260 Course description Fictional discourse is perhaps the most superficially unproblematic yet philosophically puzzling of linguistic phenomena. We usually have little difficulty distinguishing fictional from non-fictional writings. We easily make sense of what is set out within the pages of fictions, and readily agree that Pegasus is a winged horse and not a three-legged donkey. Nor are we unreflectively perplexed by the feelings aroused in us by fictions. And many of us feel that great works of fiction can help us to understand the ‘real’ world. But each of these issues - the nature of fictional discourse, its meaningfulness, our ability to determine what is true in a fiction, our capacity to be moved by or to learn from fictions - has been a subject of heated philosophical debate. Indeed, problems posed by the semantics of fictional discourse have played an important role in the thinking of some of the most influential figures in the analytic tradition, while other puzzling issues about fiction may be rendered more tractable when recast in terms of some central themes in that tradition. In this course, we shall examine some of the central issues about fictional discourse that have engaged analytic philosophers. The issues to be examined include: The Nature of Fictional Discourse A number of significantly different linguistic phenomena might be classified as forms of fictional discourse, but the core phenomenon is the use of language in fictional narratives such as the Sherlock Holmes stories. In what does the fictionality of such narratives consist? Is it simply a matter of whether they portray actual happenings and actual agents, or of the style of narration or the use of ‘literary’ techniques? Or does the fictionality of a narrative depend upon how it functions, or how it was designed to function - either the function conferred upon it by its users, or its author’s intention that it function, or be used, in a certain way? Analytic philosophers have tried to answer this question in terms of the distinctive ‘speech acts’ involved in fictional discourse. ‘Fictional Truth’, or Truth in a Fiction Understanding fictional discourse requires that we understand what is ‘true in the story’. But this cannot simply be a matter of what is explicitly affirmed by the narrator of a story, for there are deceived, or deceiving, or ironic narrators, or narrators who communicate more than they literally say. We also assume, in our reading, that many things are true in a story although they are neither explicit nor implicit in the trustworthy affirmations of the narrator. We must therefore explain how we determine the unspecified background of general propositions that are non-explicitly true in a given story. One strategy, here, appeals to what philosophers term "possible worlds" - roughly speaking, alternative ways the actual world might have been. Other philosophers have appealed to the beliefs of a hypothetical ‘fictional author’. Do either of these strategies work? Semantics of Fictional Discourse According to a widely accepted account of proper names, a proper name contributes to the meaning of a sentence only the individual it denotes: given this account, if S contains a proper name N, then it would seem that S is meaningful only if N is a genuinely denoting term. But consider sentences containing names for fictional characters, such as Sherlock Holmes. If no actual person, place, or event exists which is denoted by such a fictional name, how can we explain our seeming ability to understand sentences containing fictional names, and to hold some of them expressive of what is ‘true in the story’? There are two obvious ways in which we might resolve this dilemma: either (a) fictional names do genuinely denote, in which case we need to explain how and what they denote, or (b) S’s logical form is not as it appears to be, and, while fictional names do not function as denoting expressions, sentences containing those names are perfectly meaningful. These options, and others, resonate in the analytic tradition, in works by Meinong, Russell, Quine, and Kripke. Responding to Fictions Fictions seem able to elicit fear and other emotions in readers. But this is puzzling if we subscribe to cognitivist theories of the emotions widely accepted by contemporary analytic philosophers. The cognitivist claims that my being in an emotional state - fearing x, for example - requires not only that I have a certain feeling or am in a certain affective state but also that I believe that x endangers me or someone close to me. Given these requirements, it seems impossible for me to experience genuine fear (or, mutatis mutandis, pity) concerning what is narrated in what I take to be a fiction, because I do not believe that anyone is really in danger when I imaginatively engage with such a fiction. Can our belief that we can be genuinely moved by fictions be sustained? Cognitive Values of Fiction In what ways can we learn about the real world by reading fictional narratives? Two kinds of cognitive value have been ascribed to fiction. First, it is claimed that fictional narratives furnish us with knowledge of the real world, distinct from our learning what is true in the story. Second, it is claimed that reading fictional works effects cognitively valuable changes in the reader's emotional and perceptual dispositions. Can one or both of these claims be sustained, and, if so, how are the cognitive values of fiction to be understood? ‘Thought Experiments’ and Fictional Narratives Thought experiments, many have argued, play a crucial role in the development of science, and have also been central to contemporary philosophizing in the analytic tradition. Some have suggested that a thought experiment is a kind of fictional narrative. Should we endorse this suggestion , given what we have determined to be the nature of fictional narratives, and, if so, how can thought experiments have the place in scientific and philosophical thought that they do? Required Texts Principal readings for this course are available in a Course-pack, prepared by Eastman and on sale in the McGill Bookstore. Supplementary material will be available on reserve in the MacLennan-Redpath Library. Requirements i/ A short paper on an assigned topic (6-8 pages typed double-spaced), due at Thanksgiving, worth 40% of total grade. ii/ A term paper (12-15 pages typed double spaced), due at end of term, worth 60% of total grade. McGill University values academic integrity. Therefore, all students must understand the meaning and consequences of cheating, plagiarism and other academic offences under the Code of Student Conduct and Disciplinary Procedures (see www.mcgill.ca/integrity for more information).