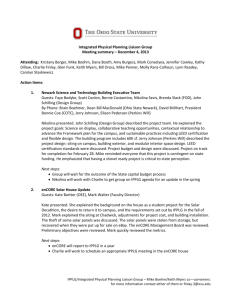

behavior assessment report and recommended support plan

advertisement