File - Emma K. Prince

advertisement

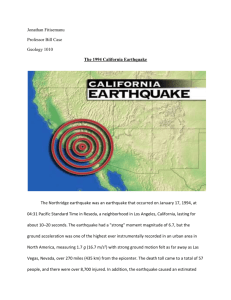

The Northridge Earthquake Emma K. Prince Nancy Pazmino GEOG 333: Natural Disasters Friday, April 25th The Northridge community, located about 30 kilometers northwest of Los Angeles, California, is located in the heavily-urbanized San Fernando Valley region and is home to over 84,000 people with a per capita income of $23,308 (11). The San Fernando Valley supports half of the city of Los Angeles’ population where 48% of the population are homeowners in the middle class (9). Northridge is known for hosting a branch campus of the California State University, being home to the New England Patriot’s quarterback Matt Cassel, and having the Ronald Reagan freeway pass through its northern region (5). Los Angeles is a very socially and culturally diverse city. It is home to: whites, Hispanics, African-Americans, and Asian-Pacific Islanders. Also, a considerable portion of the population consists of immigrants of Latinos, Southeast Asians, Koreans, and others from Pacific Rim nations and countries of Central America (3). Being so close to the Pacific Ocean, Los Angeles and all of west coast North America are included in an area of frequent earthquakes. This area, known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, is a result of the movement and collision of the Earth’s crustal plates. The instability created by the activity of these plates, produces faults that in turn produce earthquakes. “The Pacific Ring of Fire produces ninety percent of the world’s earthquakes and eighty percent of the world’s largest earthquakes” (6). On January 17, 1994, at 4:31am, Northridge and surrounding communities experienced a 6.9 Richter magnitude earthquake (8). Examinations of surface faults in the area did not reveal any disturbances, and even though LA is close to the famous San Andreas Fault, it was obvious that this specific earthquake was a result of a different fault line. Because there was no visible evidence of fault movement on the surface, geologists determined the earthquake was therefore a result of a “blind” or “hidden” thrust fault. To find the thrust fault, geologists had to examine the location of the epicenter, aftershocks, ground shaking intensity maps, ground motion maps, and the depth of the focus (2). Thousands of aftershocks occurred after the main earthquake, including a magnitude 5.9 that occurred one minute after the main shock, and a magnitude 5.6 aftershock 11 hours later. Aftershocks are a concern because they can trigger the collapse of structures that have been weakened by the initial shock (8). From geological research, we now know that the fault responsible for the Northridge earthquake is the Pico thrust fault. The earthquake lasted about 10 to 20 seconds, with the fault first moving at 10 kilometers deep; this created an offset that stretched just 5 kilometers beneath the ground, therefore it was hidden under the surface (5). Despite the fault being “hidden”, its movement caused Northridge to rise 20 centimeters or 8 inches, in addition to causing the Santa Susana Mountains just north of the San Fernando Valley 40 centimeters or 16 inches (7). According to the Mercalli intensity scale, damages caused by the earthquake reached an intensity of 9 near the epicenter. One hundred and twenty kilometers away, Mercalli intensity 5 effects were noted, and ground motions were felt as far as 300 kilometers away from the epicenter in some places (7). Damages from the earthquake included 57 deaths, and injured almost 10,000 people (5). The earthquake occurred on a Monday, ending a three day weekend which celebrated the national holiday in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King. As a result, many people were out of town which saved lives. Traffic was light due to both the early morning hour and the holiday. Although the death toll was moderate, property damage was enormous (10). Damages to houses and businesses from the earthquake far exceeded damages from other major disasters such as Hurricane Hugo and Hurricane Andrew. Up to January 1994, the Northridge earthquake was classified as the most costly natural disaster in United States history (12). This Northridge disaster was also the worst earthquake to hit Los Angeles since the 6.7 magnitude San Fernando earthquake in 1971 (8). The level of damage to buildings in the area depended on many factors: distance from the epicenter, stability of the ground beneath foundations’, and the design of the building. Over 3,000 buildings were closed from entry, and an additional 7,000 were banned from occupation (7). However, there were variations in damages observed due to different orientations of the rocks deep in the ground. Folds in deep rock layers affected how much ground motion and damage occurred at the surface. This resulted in focused waves of energy in some areas, and diffusion of this energy in others. For example: while one apartment building had no apparent damages, other buildings were split in half and completely displaced from their original foundations (7). The Northridge earthquake caused extensive damage to parking structures and freeway overpasses. Segments of California’s Interstate 5 collapsed while under construction in the 1971 San Fernando Valley earthquake. It was rebuilt with the same specifications, not retrofitted, and collapsed again during Northridge’s 1994 earthquake. The steel reinforcement bars within the concrete shattered as they were not supported and buckled from the quake. Such failure could have been prevented if the concrete had been tightly wrapped with steel. However, carefully designed, newer parking garages in the region, also thought to withstand a strong earthquake, had failed. Thankfully, due to the early morning hour, most of the buildings and parking garages that collapsed were essentially unoccupied (7). Also, a section of the Antelope Valley Freeway collapsed onto the Golden State Freeway and similarly, a section of the Santa Monica Freeway in West Los Angeles collapsed. In addition, Northridge’s branch of Cal State’s 2,500 car parking garage, located only 3 kilometers away from the epicenter also collapsed (8). The Northridge earthquake triggered landslides that damaged homes, blocked roads, and damaged water and gas lines. Gas lines damaged from the earthquake created fires intensifying the damages and making response efforts more difficult (7). Fortunately, the nearby Olive View Hospital withstood the earthquake. Like Interstate 5, this hospital had been destroyed by the 1971 San Fernando earthquake. However, after the hospital’s collapse, it was rebuilt with higher standard building codes unlike Interstate 5 (8). Direct losses from the earthquake amounted to $25 billion, and together with related losses amounted to $40 billion (12). Here, we use the term “related losses” as indirect losses or losses resulting from the consequences of physical destruction. Related losses are things such as: losses in sales, wages, and profits due to loss of function or business interruption, input/output losses, operational problems as a result of physical damages or infrastructure failure, including slowdowns and shutdowns (14). Eighteen months following the Northridge disaster, a survey was performed investigating the direct impacts and losses businesses suffered in the area. Owners reported business interruptions making it difficult to provide goods and services. The outcome of the survey revealed interesting results. It was found that 57% of the businesses surveyed endured some sort of damage; some damages were structural, some non-structural, and about 13% suffered damage severe enough to be red- or yellow-tagged. Red-tags warned of an unsafe structure while yellow restricting all entry (13). Lifeline disruptions experienced by businesses was extensive and included electricity loss, telephone service loss, water, natural gas, and/or sewer disruptions. Some sustained only one of these loses, others sustained them all. Of all businesses surveyed, 47% said that the damages suffered, mainly the loss of electricity and telephones was quite disruptive to their companies (13). In addition to these service losses, many business employees and owners were unable to get to work following the quake due to the large freeway collapses. Many had to focus on damages to their own homes before they could even think about their businesses. If these lifeline losses were not enough already, almost 40% of the surveyed businesses reported few or no customers following the earthquake; some even experienced trouble delivering goods and services. In general, smaller businesses tended to suffer more not only because of electricity loss, but because the small amount of financial backing and manpower to clean up and repair damages. These small businesses often leased their space instead of owning it, and had less say on the structural integrity of the property and how prepared it was for disaster (13). Emergency management in Northridge was completely competent in responding to problems created by the earthquake. Disasters can aggravate existing social problems, and the San Fernando Valley was experiencing problems similar to those experienced by metropolitan areas, including: pockets of high poverty, joblessness, a shortage of affordable housing, and a growing gap between the rich and the poor. The response and recovery efforts following the quake were molded by the region’s demographic diversity and its existing social and economic problems (1). Despite widespread damage throughout LA, local governments and organization had planned and exercised any and all emergency services that would be needed in the face of disaster. These plans and exercises were developed by the state of California and based on disaster scenarios. Emergency managers and disaster responders do not consider the Northridge earthquake a major disaster, as it did not overwhelm local emergency and response services. However, because the earthquake caused over $25 billion of losses it is in fact considered a disaster (4). Northridge has been a classic example of the economic disruption that can take place following an earthquake when they occur in highly urbanized areas (3). This disaster is known as the “Northridge earthquake” because it was initially thought that the earthquake’s epicenter was in Los Angeles’ Northridge community. However, the actual epicenter of the earthquake was in the neighboring community of Reseda (5). Locals were angered at the distorted media coverage Northridge received despite the earthquake’s true beginnings in the Reseda community. Even more so, other communities in the area received no media coverage at all including a community that experienced the greatest lost of residential and commercial structures. Given this, it was pointed out that media reports tended to emphasize more upscale areas in natural disasters. The naming of the Reseda-epicentered earthquake as the “Northridge” earthquake to some people revealed possible demographic biases on the media’s part. Northridge is a more upscale community than Reseda which is in majority a blue-collar community. As we mentioned before, Northridge’s per capita income is $23,308 compared to Reseda’s $15,177 per capita income. Such disparities between epicenters and media naming can have significant consequences for a community. If such disparities as biased media reporting are proven consistent, it is possible that better off, less affected communities may receive a larger portion of disaster funds, than more negatively impacted, lower income communities (11). When considering the human dimensions following the quake in this area, it is important to examine all aspects of vulnerability on a local level; vulnerability of households, and the problems that existed before the quake occurred. These include social class, gender, ethnicity, migration and residency, language/literacy, and age/life cycle (1). Social class tops most lists when considering vulnerability. In the case of Northridge, access to resources and affordable housing before the quake were limited, only exacerbating residents’ abilities to cope with property loss afterward. The communities that were affected were already faced with severe overcrowding, especially farm workers who could not afford to buy their own homes. These farmers and their families resorted to living with multiple other families in ‘single-family’ dwellings because of limited rental availability. It had already been recognized that there was a need for low-income housing in the area; however this was repeatedly ignored, and several higher-income facilities were constructed. Also, even more housing problems occurred; while it is often the case that low-income families are not home owners, such families in Northridge’s damaged areas did in fact own homes. However, their homes were mobile homes therefore making them more vulnerable. Depending on assistance following the disaster, the question of who is better off between homeowners and renters varies. Homeowners were unable to obtain resources to repair the damages because they lacked insurance, financial reserves and the ability to qualify for loans. The Northridge earthquake caused damage to nearly 5,000 homes and destroyed 184 (1). Another aspect of vulnerability is gender. While many may not consider this a major issue, such things caused problems after the quake, particularly for female farm workers. This category, while it relates to class factors, is considered a separate vulnerability. Already farm workers were considered low on the totem pole, but households lead by females were affected, more specifically than households with children under the age of 5. These households, according to the social service agencies were considered more at risk because of increased living expenses following the quake (1). Depending on whom you ask, ethnicity may also be a factor to consider when determining vulnerability caused by the Northridge earthquake. This is because, as with gender there are people who are more at risk than others. Specifically in the Northridge quake, Spanish and Mexican immigrants were at risk. This group of people displayed differences in their ability to acquire resources and recover losses (1). For example, a Central American woman (a recent immigrant of LA), had been working as a live-in nanny with a family in the San Fernando Valley. She was working in exchange for room and board and a small amount of money. The family with whom she lived and was employed, left their damaged home to move in with relatives after the earthquake; there was no room for her. She found herself homeless and jobless and unable obtain aid because she had no proof of having lost a home or employment as a result of the earthquake (11). However, in two counties of the damaged area, vulnerabilities among Latinos were unexpected. The majority of Latinos were middle to higher income, and did not share similar vulnerabilities to other Latino populations in the area (1). Some households are vulnerable in terms of political issues surrounding migration and residency. Illegal immigrants from Mexico, tend to stay with other families in single family houses or garages at night, only leaving to work in the field during the day. Immigrant workers do this in order to reduce their housing expenses. These people and houses are sometimes considered “invisible” as they have no legal identity here in the states. Thus, populations of illegal immigrants are less able to cope with losses resulting from disasters (1). After any disaster, English literacy for immigrants and residents is vitally important when applying for emergency services or government assistance. Emergency information in the U.S. is more readily available in English than any other language in the wake of disasters. This was the case in the Northridge area. Lower-income, poorly educated, non-English speaking residents had difficulty obtaining public and private resources after the earthquake due to such language barriers (1). Vulnerability is also influenced by victims’ age, or life cycle, which is a constantly changing variable. Typically, the most vulnerable in any circumstance include children and the elderly. Children obviously are dependent on their care-givers provisions and ability to recover, but they are also vulnerable to emotional stress following disasters, especially those in larger households. The elderly, specifically those forced to reside in mobile homes due to fixed incomes, found it particularly difficult to bounce back after the quake struck their communities. At the time of the quake, the average fixed income for those over 65 was under $10,000. Because of rising inflation of house values in California, the cost required to repair a home may have exceeded ten times the original purchase price. Affording the reconstruction costs for these individuals was financially impossible (1). Overall, 60% of houses in the area were red-tagged. Of those, very few were middleincome neighborhoods. Many people abandoned their houses making way for looters, squatters and street gangs. One reason why residents chose to leave their homes is that while living in an earthquake prone area, earthquake insurance is extremely expensive. Not only that, if you have earthquake coverage in your insurance plan, it would only cover the replacement of your house and not the land itself. This is a huge issue especially in California where real estate is expensive to begin with. The presence of looters, squatters and street gangs once residents abandoned their homes, lead to degradation of the society and economically hurt remaining housing, businesses and neighborhoods. While assistance was targeted in these areas, it was hard to reconstruct housing in an already weak housing market. As a consequence there was very little low income housing in LA. Because larger structures were not repaired, fixing small things like parking garages and other conveniences were even more out of the question. All of this together led to a decline and negative effect on property value (9). After such disasters, many people hope to recover and return to pre-disaster conditions. They want to achieve the status quo of the socio-economic and built environment prior to the disaster. While these hopes are understandable, they are almost impossible to achieve. At best, recovery can take the form of restructuring. While Northridge was provided with generous federal aid, those affected by the earthquake received only partial compensation for their losses and were forced to cover the rest on their own. Including the afore mentioned declining housing market, defense spending was cut, increases were seen in the liabilities of the underemployed, and insurance deductibles were rather high. The deductibles were high because they were based off of property value rather than the level of damage (9). To cover costs not provided by federal aid, many people had to change their spending patterns, draw from savings accounts and turn to credit for essential rebuilding. Because the victims overall income was lower, and so much of their money was going to essential rebuilds, many couldn’t invest as much into their local communities, hurting many small businesses. With lack of financial aid these businesses and people moved out of the damaged towns never to return. Almost 60,000 people migrated out of the area with only 20,000 moving in. These 20,000 new residents were young minorities, and poorer than those previously occupying the area. This new population not only had different retail habits, but a different culture, therefore changing the social structure of the area. Certain groups, such as this, are less likely to bring the community to the previous socio-economic and building environment. These groups are the most vulnerable in society along with immigrants, the unemployed, children and elderly people. Not only are they less likely to return the area to its previous state, but in the case of another disaster, they have limited access to resources and their vulnerability only becomes more apparent. Northridge and its surrounding communities recovered slower than hoped (9). The earthquake struck a region known to have earthquake preparedness and hazard reduction at the top of its priority list. Despite this, all disasters offer communities the chance to learn and further improve their safety measures in some way or another. After the Northridge earthquake, the area increased its number of geological hazard maps, increased building code standards, required more seismic retrofitting of older structures, and improved their emergency preparedness. Many of the problems discovered after the earthquake were determined to be construction flaws rather than design issues. In 2001, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) responded with new guidelines for steel construction in earthquake prone areas (7). In addition, response teams have offered disaster training for residents and homeowners, an emergency network was established, and community organizations were created that would provide help to vulnerable members of the community whose needs were not met through other aid services (9). References (1) Bolin, Robert, and Lois Stanford. The Northridge Earthquake: Vulnerability and Disaster. New York: Routledge, 1998. (2) Greenberg, Steve. "Blind Thrust Fault." Informational Graphics. 21 Mar. 2008 <http://www.greenberg-art.com/graphics.html>. (3) Hall, John F. "Earthquake Spectra." The Professional Journal of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (1995). (4) Nigg, Joanne M. "THE SOCIAL IMPACTS OF PHYSICAL PROCESSES." 18 Mar. 2008 <http://www.udel.edu/DRC/preliminary/238.pdf>. (5) "Northridge Earthquake." Wikipedia. 21 Mar. 2008 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northridge_earthquake>. (6) "Earthquake Hazard Program." USGS. 18 Apr. 2008 <http://earthquake.usgs.gov/learning/faq.php>. (7) Hyndman, Donald, and David Hyndman. Natural Hazards and Disasters. CA: Thomson, 2006. (8) "NORTHRIDGE 1994." 18 Apr. 2008 <http://www.vibrationdata.com/earthquakes/northridge.htm>. (9) Petak, William J., and Shirin Elahi. "The Northridge Earthquake, USA and Its Economic and Social Impacts." 21 Mar. 2008 <http://www.iiasa.ac.at/Research/RMS/july2000/Papers/Northridge_0401.pdf>. (10) Place, Susan, and Christine M. Rodrigue. "MEDIA CONSTRUCTION OF THE "NORTHRIDGE" EARTHQUAKE IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH LANGUAGE PRINT MEDIA IN LOS ANGELES." Center for Hazards Research. 21 Mar. 2008 <http://www.csulb.edu/~rodrigue/igu1994.html>. (11) Rovai, Eugenie. "Developing a Conceptual Framework: Media Coverage, Mental Maps and Response to Disaster." (12) Tierney, Kathleen J. "Business Impacts of the Northridge Earthquake." Contingencies and Crisis Management 5 (1997). (13) Tierney, Kathleen J., and James M. Dahlhamer. "Business Disruption, Preparedness and Recovery: Lessons From the Northridge Earthquake." Disaster Research Center (1997). (14) "The Impacts of Natural Disasters: a Framework for Loss Estimation." National Academic Press (1999). 13 Apr. 2008 <http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=6425&page=37>.