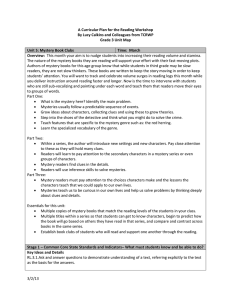

The Principles of Mystery

advertisement

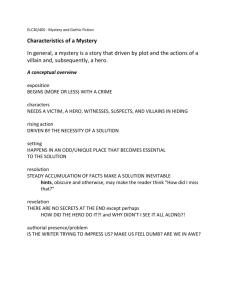

The Principles of Elementary Mystery Writing by Carol A. Withrow Each day of life holds some shards of mystery. Mysteries in life range from the mundane such as missing items, to actions of misdeed created by criminals, to the unknown realms themselves. Residing deep within basic human nature is the curiosity and intrinsic motivation to solve these puzzles. Fourth grade mysteries often revolve around an absent or misplaced item, or a strange noise or occurrence, rather than the murderous plots generated in the adult world. Therefore, the genre of mystery is often viewed with highinterest by young authors as they strive to make direct connections to the complications of real-life. The principles of crafting a mystery can be easily identified by most students when contemplating the classic “Scooby Doo” episodes. Briefly related, an unexplained problem arises which requires a character, usually the narrator, to divulge the logical thinking processes of a detective in order to unravel the conundrum. As detailed by Jeffery Feinman in The Mysterious World of Agatha Christie (p.131, Award Books, 1975), “It is in the personality and the analytic faculties of the detective that all knots are untied, all puzzles solved. It is he, or just as often, she who carries the ball of colored yarn through the maze, trailing a string for the reader to follow. The detective stands for the reader himself, poking his nose into hidden corners, finding out what the reader wants to know.” It is the duty of the author of mystery to develop a problem which initially appears to have multiple possibilities or outcomes. The author then portrays a number of characters equipped with motives and suspicious actions, while weaving the reader through a trail of clues to the final outcome. Although the piece will continually develop through revision, it is best to carefully plan the puzzle from the start. When the solution of the mystery involves human miscommunication or crime (not an act of nature), a definite pattern tends to emerge as illustrated by “Scooby Doo”. Throughout the whodunit, one character appears the obvious culprit for a number of suspicious reasons (yet remains innocent in the end), while the helpful and obliging character during the investigation proves to be the guilty party. This basic premise of plot twist or “complication” in mysteries results in a formula that promotes success and pleasure in writing in students of all ages. When crafting a mystery, please keep in mind the following: Develop the idea of your ending before beginning your lead. Decide what clues your detective will discover and how they will relate to your characters. Conference with others as you write and revise. Organize resources for your mystery-writing club to utilize. Post the mystery web created as a class, and other reminders of the purpose of mystery that help students to better develop their own ideas. o A “Clue Bank” allows for students to share ideas for clues. Students may draw from the clue bank when in need. Some clues may include: strange noises or light, footprints or tracks left in a muddy area, a fragment of an overheard conversation, a piece of a note or letter, part of a news article, something dropped by a suspect, unusual equipment, wet paint, a trace of something left behind (hair, a piece of fabric, jewelry, a tag, torn paper), the use of codes, etc. o A “Suspicious Behavior Bank” may also be beneficial and could include: shifty eyes, lack of eye contact, stammering speech, sweaty palms or brows, hurried or unorganized departures, avoidance, sneaky entrances, exaggerated clothing, unusual or disguised handwriting or speech, aggression or a sense of defensiveness, incriminating comments, knowing specific details related to the crime or missing item, etc. Keep your purpose in mind. As you develop your plot and characters and logically organize your selected clues, paint vivid pictures for the reader as they travel through the maze of your puzzle. And remember most importantly, crafting mysteries is fun!!!