A Curricular Plan for the Reading Workshop

advertisement

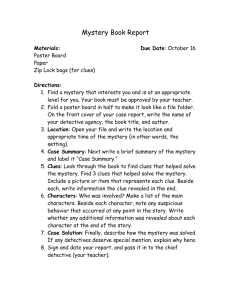

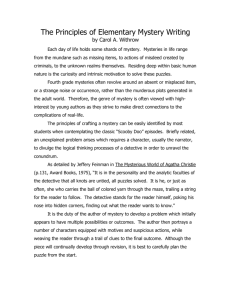

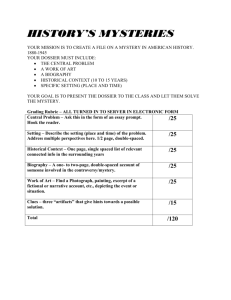

A Curricular Plan for the Reading Workshop By Lucy Calkins and Colleagues from TCRWP Grade 3 Unit Map Unit 5: Mystery Book Clubs Time: March Overview: This month your aim is to nudge students into increasing their reading volume and stamina. The nature of the mystery books they are reading will support your effort with their fast-moving plots. Authors of mystery books for this age group know that while students in third grade may be slow readers, they are not slow thinkers. These books are written to keep the story moving in order to keep students’ attention. You will want to track and celebrate volume surges in reading logs this month while you deliver instruction around reading faster and longer. Now is the time to intervene with students who are still sub-vocalizing and pointing under each word and teach them that readers move their eyes to groups of words. Part One: What is the mystery here? Identify the main problem. Mysteries usually follow a predictable sequence of events. Grow ideas about characters, collecting clues and using these to grow theories. Step into the shoes of the detective and think what you might do to solve the crime. Teach features that are specific to the mystery genre such as: the red herring. Learn the specialized vocabulary of the genre. Part Two: Within a series, the author will introduce new settings and new characters. Pay close attention to these as they will hold many clues. Readers will learn to pay attention to the secondary characters in a mystery series or even groups of characters. Mystery readers find clues in the details. Readers will use inference skills to solve mysteries. Part Three: Mystery readers must pay attention to the choices characters make and the lessons the characters teach that we could apply to our own lives. Mysteries teach us to be curious in our own lives and help us solve problems by thinking deeply about clues and details. Essentials for this unit: Multiple copies of mystery books that match the reading levels of the students in your class. Multiple titles within a series so that students can get to know characters, begin to predict how the book will go based on others they have read in that series, and compare and contrast across books in the same series. Establish book clubs of students who will read and support one another through the reading. Stage 1 – Common Core State Standards and Indicators– What must students know and be able to do? Key Ideas and Details RL.3.1.Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers. 3/2/13 RL.3.3. Describe characters in a story (e.g., their traits, motivations, or feelings) and explain how their actions contribute to the sequence of events. Craft and Structure RL.3.5 Refer to parts of stories, dramas, and poems when writing or speaking about a text, using terms such as chapter, scene, and stanza; describe how each successive part builds on earlier sections. Integration of Knowledge and Ideas RL.3.9. Compare and contrast the themes, settings, and plots of stories written by the same author about the same or similar characters (e.g., in books from a series). Speaking and Listening Comprehension and Collaboration SL.3.1. Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacherled) with diverse partners on grade 3 topics and texts, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly. Presentation of Knowledge and Ideas SL.3.6. Speak in complete sentences when appropriate to task and situation in order to provide requested detail or clarification. Essential Questions for Students Guiding Questions for Teachers How can I read mysteries, following and interpreting the clues and the patterns of the genre, so that I not only solve the mystery but learn the valuable life lessons embedded in the text? How can I help my students puzzle over clues using their fiction reading skills and the predictable narrative structure specific to mysteries in order to make smart predictions as they read? How can I help my students navigate mysteries, making inferences to formulate theories, which they can then continue to revise by evaluating and reevaluating the evidence as they go? How can I help my students notice and analyze characters' motivations, choices, and emotions so that they learn life lessons from these texts, rather than simply breezing through mysteries as "plot junkies?" Stage 2– Common Assessment – What is the evidence of understanding? Universal Screens Formative Assessment Strategies Post-it Notes Reading Notebooks Conference notes 3/2/13 Stage 3 – Instruction – What learning experiences will lead to understanding? Skills: Key Terms/Vocabulary Domain Specific Questioning Vocabulary Summarizing volume Main Idea stamina Inferring fluency Compare and Contrast texts story arc Envisioning narrative text Analysis predictable sequence of events growing ideas about characters prediction inference/reading between the lines interpretation Tier Two Words Detective Sleuth Suspects Witness Clues Motive/ Motivation Opportunity Alibi Evidence Red herring Crime scene Sidekick Plot twist Villain Suspicious Eureka! Words that Describe Character Motives Jealousy Revenge Greed 3/2/13 One Possible Sequence of Teaching Points (A Note To Teachers: Please remember that this one possible sequence of teaching points. Based on the students in your class, you may decide to spend more time on some things and not others. This is a guide to help you make decisions based on the learners in front of you.) Part One: How can I help my students puzzle over clues using their fiction reading skills and the predictable narrative structure specific to mysteries in order to make smart predictions as they read? Mystery readers start our books wondering, “What’s the mystery?” We read the first few pages trying to identify the main problem. Next, we ask ourselves, “Who’s the main detective? Is this main detective one person or a group of people?” Then, we read deeper into the book, paying attention to the clues this main detective finds. Mystery readers often step into the main detective’s shoes, almost solving the mystery alongside this character. We try to see whatever the main detective might be seeing, consider all the clues, and keep guessing at possible solutions, almost as if we were the main detective ourselves. Mystery readers read for clues. We notice and think about all the information we are getting and say to ourselves, "This might be important because..." This helps us to talk about possibilities for how the story may go. Mystery readers read with suspicion. We make a list of suspects as we read, and each time a new character enters the story we think, “Could this person be responsible? Is this character telling the truth or is he/she guilty?” We pay attention to the little details in the story that point to whether a character should be on our list of suspects or not. We also think of motives, asking ourselves, “Why would this suspect want to do this? What does he or she have to gain?” Mystery readers retrace our steps if we need to. Just as the main characters in mysteries often go back to the crime scenes to revisit and study clues, we can go back and reread a portion of the story and study the information the author has given us in order to help us solve the mystery. Mystery readers, like detectives, rethink everything. As we read deeper into the book, we consider old clues in the light of new information. We ask, “How does what I’m reading now fit with what came before?” Often, we revise our predictions because the story shows us a new angle or clue that we didn’t know previously. Sometimes a mystery reader sees more than the main detective does. We almost want to shout to the main character: “look out!” or “pay attention!” It’s at moments such as these that mystery readers practically become detectives ourselves. Although mystery readers can often sniff out a false clue, sometimes the author tricks us with a red herring. We consider the specific red herrings (false clues) that threw us off course, wondering, "What did the author do to trick me? What did this make me think?" We vow, "Now I know...I will not fall for this particular red herring in any future mystery I read!" Part 2: How can I help my students navigate mysteries, making inferences to formulate theories, which they can then continue to revise by evaluating and reevaluating the evidence as they go? Readers begin a new book in a mystery series expecting to see familiar faces and places. We know that many mysteries in a series follow a familiar pattern. They often begin in the same place and have characters who repeat, so that after a while, these characters start to feel almost like old friends. When we read a third and fourth book in a series, we come to know the main detective’s habits and strengths, and we can sometimes predict how this character will think or behave or the steps that this 3/2/13 main character will take to solve a mystery. Mystery readers pay attention not just to the main detective, but also to the sidekick or friends who helps this main detective. We notice that often, while talking to this sidekick, the main detective comes up with new solutions. As we read many books in the same series, we note whether the sidekick changes across books or stays the same. For example, sometimes the sidekick seems to grow smarter with each new mystery, or sometimes he or she surprises us by acting in an unpredictable way. We wonder what it means when this happens. Just like detectives often solve a mystery with the help and intelligence of their friends, mystery readers, too, ponder our books with other mystery readers. When we talk to other mystery readers, we often use the language of prediction. We start off our sentences saying, “I think this might mean…” or “Maybe this shows…” Sometimes, we use the language of wondering or questioning and we begin our sentences with “How could…” or “Why would…” Part 3: How can I help my students notice and analyze characters' motivations, choices, and emotions so that they learn life lessons from these texts, rather than simply breezing through mysteries as "plot junkies?" Mystery readers can learn a lot by studying the choices that characters in our books make. The small choices that a character makes don’t just define that character; they can also guide the choices we make in our own lives. Mysteries teach readers many valuable lessons about life. Whenever we solve a mystery, we learn something new about human nature. We ask ourselves, “Why would this person do this thing?” Often the answer is “greed,” “jealousy,” “revenge,” or some other negative motive. Mysteries teach us that crimes don’t remain unsolved and that negative motives are often uncovered and punished. Reading mysteries teaches us to be curious in our own lives. Mystery readers become trained to look for clues and details in our real lives that tell us more than someone else might see. We notice and think deeper about things someone else might pass by and solve problems in our own lives by rethinking and pondering these. Resources: Calkins, Lucy and Colleagues. 2011-2012. A Curricular Plan for the Reading Workshop Grade 3. Unit 5 Mystery Book Clubs. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Mentor Texts: Websites and Technology: 3/2/13