Architecture of the Liver

advertisement

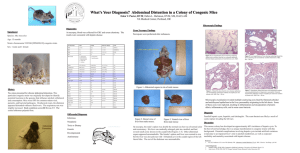

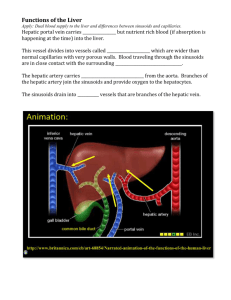

Architecture of the Liver The liver is the largest gland in the body and performs an astonishingly large number of tasks that impact all body systems. One consequence of this complexity is that hepatic disease has widespread effects on virtually all other organ systems. At the risk of losing site of the forest by focusing on the trees, we will focus on three fundamental roles of the liver: Vascular functions, including formation of lymph and the hepatic phagocytic system. Metabolic achievements in control of synthesis and utilization of carbohydrates, lipids and proteins. Secretory and excretory functions, particularly with respect to the synthesis of secretion of bile. The latter is the only one of the three that directly affects digestion - the liver, through its biliary tract, secretes bile acids into the small intestine where they assume a critical role in the digestion and absorption of dietary lipids. However, understanding the vascular and metabolic functions of the liver is critical to appreciating the gland as a whole. Architecture of the Liver and Biliary Tract The liver lies in the abdominal cavity, in contact with diaphragm. As seen in image to the right of a mouse liver, its mass is divided into several lobes, the number and size of which vary among species. In most mammals, a greenish sac - the gall bladder - is seen attached to the liver and careful examination will reveal the common bile duct, which delivers bile from the liver and gall bladder into the duodenum. Understanding function and dysfunction of the liver, more than most other organs, depends on understanding its structure. The major aspects of hepatic structure that require detailed attention include: The hepatic vascular system, which has several unique characteristics relative to other organs. The biliary tree, which is a system of ducts that transports bile out of the liver into the small intestine. The three dimensional arrangements of the liver cells, or hepatocytes and their association with the vascular and biliary systems. The Hepatic Vascular System The circulatory system of the liver is unlike that seen in any other organ. Of great importance is the fact that a majority of the liver's blood supply is venous blood! The pattern of blood flow in the liver can be summarized as follows: Roughly 75% of the blood entering the liver is venous blood from the portal vein. Importantly, all of the venous blood returning from the small intestine, stomach, pancreas and spleen converges into the portal vein. One consequence of this is that the liver gets "first pickings" of everything absorbed in the small intestine, which, as we will see, is where virtually all nutrients are absorbed. The remaining 25% of the blood supply to the liver is arterial blood from the hepatic artery. Terminal branches of the hepatic portal vein and hepatic artery empty together and mix as they enter sinusoids in the liver. Sinusoids are distensible vascular channels lined with highly fenestrated or "holey" endothelial cells and bounded circumferentially by hepatocytes. As blood flows through the sinusoids, a considerable amount of plasma is filtered into the space between endothelium and hepatocytes (the "space of Disse"), providing a major fraction of the body's lymph. Blood flows through the sinusoids and empties into the central vein of each lobule. Central veins coalesce into hepatic veins, which leave the liver and empty into the vena cava. The Biliary System The biliary system is a series of channels and ducts that conveys bile - a secretory and excretory product of hepatocytes - from the liver into the lumen of the small intestine. Hepatocytes are arranged in "plates" with their apical surfaces facing and surrounding the sinusoids. The basal faces of adjoining hepatocytes are welded together by junctional complexes to form canaliculi, the first channel in the biliary system. A bile canaliculus is not a duct, but rather, the dilated intercellular space between adjacent hepatocytes. Hepatocytes secrete bile into the canaliculi, and those secretions flow parallel to the sinusoids, but in the opposite direction that blood flows. At the ends of the canaliculi, bile flows into bile ducts, which are true ducts lined with epithelial cells. Bile ducts thus begin in very close proximity to the terminal branches of the portal vein and hepatic artery, and this group of structures is an easily recognized and important landmark seen in histologic sections of liver - the grouping of bile duct, hepatic arteriole and portal venule is called a portal triad. Small bile ducts, or ductules, anastomose into larger and larger ducts, eventually forming the common bile duct, which dumps bile into the duodenum. A sphincter known as the sphincter of Oddi is present around the common bile duct as it enters the intestine. The gall bladder is another important structure in the biliary system of many species. This is a sac-like structure adhering to the liver which has a duct (cystic duct) that leads directly into the common bile duct. During periods of time when bile is not flowing into the intestine, it is diverted into the gall bladder, where it is dehydrated and stored until needed. Architecture of the Hepatic Parenchyma The liver is covered with a connective tissue capsule that branches and extends throughout the substance of the liver as septae. This connective tissue tree provides a scaffolding of support and the highway which along which afferent blood vessels, lymphatic vessels and bile ducts traverse the liver. Additionally, the sheets of connective tissue divide the parenchyma of the liver into very small units called lobules. The hepatic lobule is the structural unit of the liver. It consists of a roughly hexagonal arrangement of plates of hepatocytes radiating outward from a central vein in the center. At the vertices of the lobule are regularly distributed portal triads, containing a bile duct and a terminal branch of the hepatic artery and portal vein. Lobules are particularly easy to see in pig liver because in that species they are well delineated by connective tissue septae that invaginate from the capsule. Additional information on liver structure is presented in the sections on hepatic histology. Physiology of the Hepatic Vascular System Hepatic Blood Volume and Reservoir Function The liver receives approximately 30% of resting cardiac output and is therefore a very vascular organ. The hepatic vascular system is dynamic, meaning that it has considerable ability to both store and release blood - it functions as a reservoir within the general circulation. In the normal situation, 10-15% of the total blood volume is in the liver, with roughly 60% of that in the sinusoids. When blood is lost, the liver dynamically adjusts its blood volume and can eject enough blood to compensate for a moderate amount of hemorrhage. Conversely, when vascular volume is acutely increased, as when fluids are rapidly infused, the hepatic blood volume expands, providing a buffer against acute increases in systemic blood volume. Formation of Lymph in the Liver Approximately half of the lymph formed in the body is formed in the liver. Due to the large pores or fenestrations in sinusoidal endothelial cells, fluid and proteins in blood flow freely into the space between the endothelium and hepatocytes (the "space of Disse"), forming lymph. Lymph flows through the space of Disse to collect in small lymphatic capillaries associated with portal triads (the reason they are not called portal tetrads is because these lymphatic vessels are virtually impossible to identify in standard histologic sections), and from there in the systemic lymphatic system. As you might expect, if pressure in the sinusoids increases much above normal, there is a corresponding increase in the rate of lymph production. In severe cases the liver literally sweats lymph, which accumulates in the abdominal cavity as ascitic fluid. What lesions can you envision that would raise blood pressure in sinusoids, resulting in production of ascites? The Hepatic Phagocytic System The liver is host to a very important part of the phagocytic system. Lurking in the sinusoids are large numbers of a type of tissue macrophage known as the Kupffer cell. Kuppfer cells are actively phagocytic and represent the main cellular system for removal of particulate materials and microbes from the circulation. Their location just downstream from the portal vein allows Kupffer cells to efficiently scavenge bacteria that get into portal venous blood through breaks in the intestinal epithelium, thus preventing invasion of the systemic circulation.