Course Syllabus

advertisement

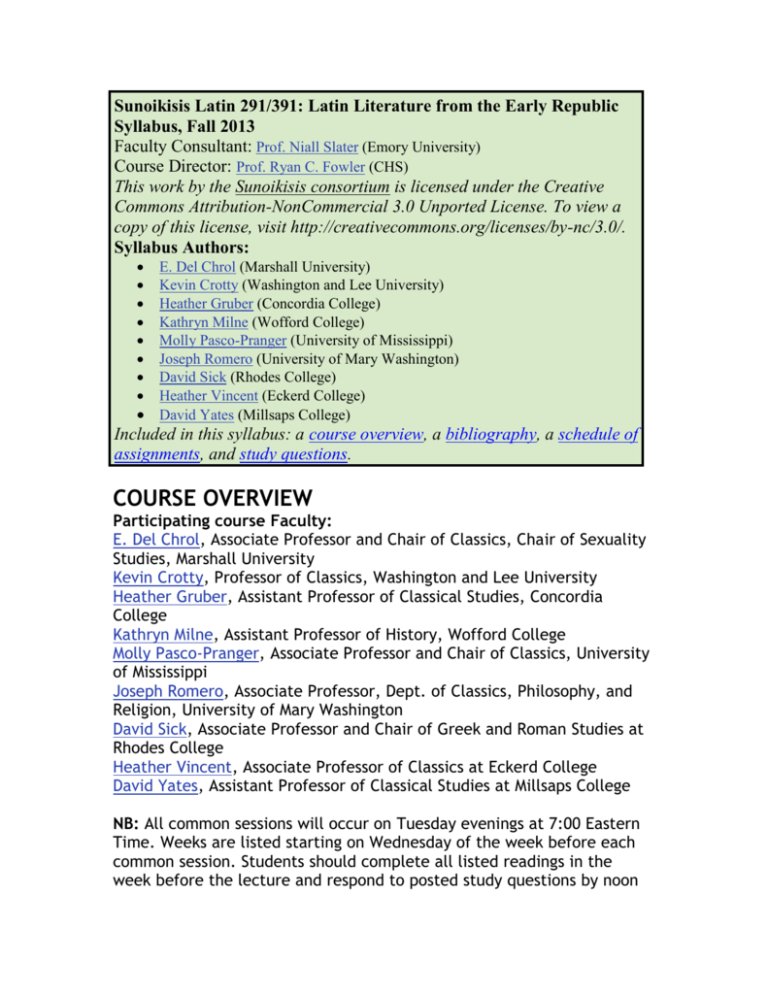

Sunoikisis Latin 291/391: Latin Literature from the Early Republic Syllabus, Fall 2013 Faculty Consultant: Prof. Niall Slater (Emory University) Course Director: Prof. Ryan C. Fowler (CHS) This work by the Sunoikisis consortium is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/. Syllabus Authors: E. Del Chrol (Marshall University) Kevin Crotty (Washington and Lee University) Heather Gruber (Concordia College) Kathryn Milne (Wofford College) Molly Pasco-Pranger (University of Mississippi) Joseph Romero (University of Mary Washington) David Sick (Rhodes College) Heather Vincent (Eckerd College) David Yates (Millsaps College) Included in this syllabus: a course overview, a bibliography, a schedule of assignments, and study questions. COURSE OVERVIEW Participating course Faculty: E. Del Chrol, Associate Professor and Chair of Classics, Chair of Sexuality Studies, Marshall University Kevin Crotty, Professor of Classics, Washington and Lee University Heather Gruber, Assistant Professor of Classical Studies, Concordia College Kathryn Milne, Assistant Professor of History, Wofford College Molly Pasco-Pranger, Associate Professor and Chair of Classics, University of Mississippi Joseph Romero, Associate Professor, Dept. of Classics, Philosophy, and Religion, University of Mary Washington David Sick, Associate Professor and Chair of Greek and Roman Studies at Rhodes College Heather Vincent, Associate Professor of Classics at Eckerd College David Yates, Assistant Professor of Classical Studies at Millsaps College NB: All common sessions will occur on Tuesday evenings at 7:00 Eastern Time. Weeks are listed starting on Wednesday of the week before each common session. Students should complete all listed readings in the week before the lecture and respond to posted study questions by noon the Saturday before the common session, so that faculty and other students will have the opportunity to review responses. Description This course, making extensive use of Internet resources, focuses on the evolution of Latin comedy during the early Republican Roman era. During the course we will read Plautus’ Pseudolus as a primary text alongside other texts of the period, in addition to secondary articles, video clips, and texts in translation. Although the course will touch upon many themes (e.g. performance, the nature of Roman humor, reception), the role of Comedy within the development and evolution of Roman literature is the overarching concern of the course. Students will participate in a weekly webcast lecture, an on-line discussion moderated by faculty members from participating institutions, and weekly tutorials with faculty members at their home institutions. Objectives This course is specifically designed for advanced students and will include a rigorous study of cultural and historical contexts during the early Republican period. Students will continue developing their understanding of the language by closely reading Latin as found in a number of our existing Roman comedies in the context of the evolution of Roman literature. The goals of this course are to read and enjoy Republican poetry with full comprehension of form and content; to master its genres and conventions and follow essential points of written discourse; to demonstrate an awareness of the aesthetic properties of early Republican Latin language and literary style and how these differ from other snapshots of the Latin language; and to work to understand the historical, social, and cultural worlds of the Republican period. Course Components Preparation: As noted below, readings are organized by common session, and students should read all assigned primary texts before the common session (ideally before answering the corresponding writing prompt). Students who choose to take this course at the 291 rather than 391 level will be responsible for less reading in Latin but will be expected to complete all of the reading in English. Common Sessions: Tuesdays, 7-8:15 PM Eastern. Students at all participating institutions will meet together online for a common session via multipoint interactive video-conferencing and a chat room. These interactive sessions have a different faculty leader each week and typically combine mini-lectures with discussion, questions, and exercises. Study Questions: Responses to the study question(s) are due Saturday by noon; between then and the common session, please provide at least one substantial comment to two other students' posts. The study questions afford students the opportunity to expand on and synthesize issues that arise in the reading and common session, as well as engage with secondary literature. Students may be asked to complete additional reading in English for the study questions. Due Dates and Times for Discussion Questions: Initial answers to study prompts are due noon EST on Saturdays, and responses to two other students' answers are due before that week’s Common Session. Tutorials: Each student will meet for at least one hour every week with a mentor at her or his home institution. The times and locations of these meetings will be determined on each campus. Students are responsible for contacting their faculty mentors and finalizing the details of their weekly meetings. These sessions will focus more closely on issues of language, translation and interpretation of assigned readings. Home campus mentors will be the final authority for all grades. Examinations: Translation exams and quizzes will be handled by home institutions, but there will be a communally designed essay-based final exam that will be administered and graded by course faculty as a whole. There will be Google Hangout office hour Friday from 11-12pm EST. The course weeks will be September 4 through November 19th. There is a midterm break between Oct. 9th-15th. For students in Latin 291, grades will be based on the following components: Class preparation and work in tutorial: 40% Participation in the study questions: 30% Midterm examination: 15% Final examination: 15% For students in Latin 391, grades will be based on the following components: Class preparation and work in tutorial: 30% Participation in the study questions: 30% Midterm examination: 20% Final examination: 20% COURSE BIBLIOGRAPHY Suggested Texts: Most texts and commentaries will be made available in the resources section of the Sakai site for the class, but individual faculty may require students to purchase the primary text used in the course. Hard copy text: M.M. Willcock. Pseudolus. Bristol Latin Texts Series. 1991. Electronic text of the play can be found on Perseus Additional resource: Lewis, Charlton and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary. Oxford, 1879. A good web interface for Lewis and Short is Glossa. Secondary readings: Favro, D. and Christopher Johanson. 2010. “Death in Motion: Funeral Performance in the Roman Forum.” JSAH 69. Gargola, Daniel J. 2010. “The Mediterranean Empire (264-134)” in A Companion to the Roman Republic. Blackwell, pp. 147-166. Goldberg, S. M. 2005. “Introduction” to Constructing Literature in the Roman Republic. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, pp. 1-19. Goldberg, Sander M. 1998. “Plautus on the Palatine,” JRS 88: 1-20. Leigh, Matthew. 2004. “Plautus and Hannibal” in Comedy and the Rise of Rome. Oxford University Press, pp. 24-56. Marshall, C. W. 2006. The Stagecraft and Performance of Roman Comedy. Cambridge University Press. McCart, Gregory. 2007. "Masks in Greek and Roman Theatre" in The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre, pp. 247-267. Richlin, Amy. 2005. “Introduction” to Rome and the Mysterious Orient. University of California Press, pp. 1-54. SCHEDULE OF READINGS AND COMMON SESSIONS (Texts and links for each session's are available in the Resources folder.) Introductory Common Session (Sept. 3rd) Tuesday “Introduction to the course, technology, logistics, etc.” (Ryan Fowler, CHS) First Common Session (Sept. 10th) Latin reading: Up to Line 61 (594 words) Common Session assignment: On the background of Roman comedy and the structure of Plautus' Pseudolus, please read the introduction to the Willcock text, pp. 1-17. To get us thinking about comedy and laughter, please read the the first scene from Aristophanes’ comedy Frogs (lines 1-37), which was first performed in 405 BCE. In this scene, Dionysus and his slave Xanthias argue about what is funny. Next, please watch the first scene of an episode of the TV show, 30 Rock—“Stone Mountain,” Season 4, Episode 3 (Oct. 29, 2009). In this episode, Liz Lemon, a comedy writer, and her boss, Jack Donaghy, argue about what is funny. The opening scene is available on Youtube. You need only watch as far as 1:17. After reading the passage from Aristophanes and viewing the 30 Rock clip, please discuss the following in a brief 300-400 word essay: What makes something funny? In your answer, please make reference to Aristophanes scene and the Tina Fey clip. You might discuss such questions as: What are the different positions staked out in these two pieces? Do you find any similarities in the positions taken in the ancient and modern pieces? What is funny in each scene? Are arguments about what is funny funny? Tuesday “Evolution of Comedy” (Kevin Crotty, Washington and Lee University) Second Common Session (Sept. 17th) Latin reading: to Line 158 (789) Common Session assignment: Please Read: Cato the Elder, On Agriculture 2, 56-59 (in English) Matthew Leigh, “Plautus and Hannibal” in Comedy and the Rise of Rome, Oxford University Press 2004; pp.24-56. Daniel J. Gargola, “The Mediterranean Empire (264-134)” in Rosenstein and Morstein-Marx, (eds.), A Companion to the Roman Republic, Blackwell 2010; pp.147 – 166. Plautine comedy, as Leigh points out, is a Roman adaptation from a Greek model, presented in the wake of a near-disastrous Carthaginian war which profoundly influenced the Roman psyche. Please take 300-400 words and discuss the following: “In what way(s) do you think the Romans distinguish themselves from the Greeks and Carthaginians, and deliberately mould their image as unique, in opposition to the perceived qualities of these other peoples?” Tuesday “Socio-historical Context: Who were the Romans?” (Kathryn Milne, Wofford College) Third Common Session (Sept. 24th) Latin reading: to Line 257 (1002) Common Session assignment: Please read: S. M. Goldberg, ‘Introduction’ to Constructing Literature in the Roman Republic. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005. Pp. 1-19; Livy 7.2 (on the introduction of drama to Rome) Then answer (and post) the following three questions: 1. (200 words) According to Goldberg (8), Livy's account of the introduction of scenic drama at Rome "has defied a century or more of intense scrutiny," and "Nothing about the passage is clear." Please explain these statements by providing specific examples from the passage. What difficulties do you see in the passage and why? 2. (200 words) Without consulting any primary or secondary sources, using only the knowledge that is in your head right now, write a paragraph explaining the origins of American literature. 3. (200 words) How do the problems you encountered in explaining the origins of American literature compare to those Goldberg discusses regarding the origins of Roman literature? Tuesday “Teacher, ‘Where did Roman Literature Come from?’” (David Sick, Rhodes College) Fourth Common Session (Oct. 1th) Latin reading: to Line 370 (1093) Common Session assignment: Reading in English, with the Latin next to you, read the prologues of Terence: Andria, Hecyra, Eunuchus, Phormio, Heautontimoroumenos, Adelphoe Please take 300-400 words and discuss the following: Have you seen "The Wizard of Oz"? (I hope so.) Read all of Terence's prologues in Latin and/or English and write a prologue to WOO in the Terentian style. Consider the elements of Terence's prologues. How long are they? Who speaks them? What kinds of things do they (must they) say? Extra points if it's in meter. And, yes, the prologue should be in English, though Latin hexameters are always welcome. Tuesday “Terence’s Prologues” (Joseph Romero, University of Mary Washington) Fifth Common Session (Oct. 8th) Latin reading: to Line 522 (1203) Common Session assignment: Read: Sander M. Goldberg, “Plautus on the Palatine,” JRS 88 (1998): 1-20. In English with Latin at hand: Plautus, Curculio 462-86. The Goldberg article gives you a good sense of the setting in which our central play, the Pseudolus, was likely staged the first time around. We’ll talk more about that in the common session on Tuesday. For your thinking questions for this week, I’d like you to consider an excerpt from another Plautine play, the Curculio. The passage is a little intermezzo delivered by the company manager while some important plot business goes on offstage—the parasite Curculio has just run off to trick a pimp and collect a girl for his young master: enter the choragus. You will want to consult the map provided as you read his speech. Respond thoughtfully and at some length (a sturdy paragraph or two for each) to at least two of the following questions; answer each in a separate post; feel free to answer all three if you find you’ve got good things to say. Creativity in mode of response is welcome and encouraged. Please finish your initial posts by Saturday noon, and respond to at least two of your peers’ posts before Tuesday’s common session. Imagine yourself as the speaker of this monologue. Where is the stage on which you’re standing? Which direction are you facing? (How) will you gesture to the places you mention? Can you see them? Can your audience? What tone do you take with the audience? As you finish your spiel, are the audience members cheering, laughing, booing, clearing their throats uncomfortably? Give yourself a Roman social identity and place yourself specifically in space as an audience member of the Curculio. Where do you stand, both literally and figuratively, in relation to the choragus’ speech? Are you as comfortable in your position as you were before he walked on stage? The choragus’ speech is distinctly metatheatrical: it breaks the illusion of the play, draws attention to its status as play, to the audience’s status as audience, etc. Is the choragus in the play or isn’t he? Pull out and discuss one effect this metatheatrical moment might have, or one way that its presence in this play might lead you to think about the Pseudolus, or Roman comedy broadly, differently. Tuesday “A Play Takes Place: Comedy in the Roman City” (Molly Pasco-Pranger, University of Mississippi) (PPT presentation) •Romelab.02: Performance on the Ephemeral Stage http://romelab.etc.ucla.edu/projects/ •D. Favro and Christopher Johanson, “Death in Motion: Funeral Performance in the Roman Forum” in JSAH 69 (2010) http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jsah.2010.69.1.12 Midterm Break Oct. 9-15 Sixth Common Session (Oct. 22nd) Latin reading: to Line 659 (1291) Reading song lyrics and attending a live concert are not the same thing. Ultimately, we miss a lot when we ‘read’ Plautus without an appreciation for the experience of attending the Roman theater. For this week we will not only be reading, but also listening and performing to get a better sense of what it would have been like to watch Plautine plays live. Our primary reading (Poenulus) addresses the basic question of distractions. One of our secondary readings (Marshall) builds on this same issue. The other (McCart) directs our attention to the actors, particularly the masks they would have worn and their impact on the performance. I have also assigned an excerpt of real Plautine meter sung in Latin to draw attention to the musicality of Roman comedy. The rest of the assignment should be completed in small groups (of three ideally). In Plautus’ day the Romans did not perform in devoted theater spaces. Locations varied, and so did the acoustics. I would like you to test the acoustics (and distraction levels) of different kinds of spaces on your campus by reciting some Plautus…in public! Details below. Primary Readings: Poenulus 1-45 (in English) Secondary Readings: G. McCart. 2007. “Masks in Greek and Roman Theatre,” in M. McDonald and J. Walton (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Roman Theatre. Cambridge. C.W. Marshall. 2006. Stagecraft and Performance in Roman Comedy, Cambridge. pages 45-48 ONLY. Listen to the meter (select any one sample) at: http://camws.org/CJ/files/108.2/meter/Canticarecordings/01Recording sintro.html Performance (weather permitting): 1. 1. 2. 3. Nominate an ‘actor’ to read any 20 lines of Plautus (in English or Latin!) in one of the types of spaces listed below. The use of Halloween masks is not discouraged. An open green (while crowded) Facing the steps in front of an academic building (while crowded) A formal theater space (outside if possible, but no crowds needed) 2. Nominate a ‘camera person’ to film the recitation and upload it to Youtube. 3. Have a third group member, in consultation with the rest of the group, answer the study question below. (Just a final note, instructors should feel free to play around with the distribution of labor as class and group size demands.) Common Session assignment (300-400 words): You have just returned from Plautus’ recent hit, the Pseudolus. Your brother is travelling, but wants to hear all about your day at the theater. Write a letter that details the sights and sounds of the performance. Tuesday “Down in Front!!! The Experience of the Roman Theater” (David Yates, Millsaps College) Seventh Common Session (Oct. 29th) Latin reading: to Line 803 (1310) Read: Review Lines: 415-573 (the scene with Pseudolus, Callipho and Simo; Act 1, Scene 5) Richlin’s introduction to Rome and the Mysterious Orient, especially pages 15-30. On page 3 of Richlin’s introduction she writes about Plautine comedy, “…the plays interpellate the audience segmentally and intermittently. That is, different lines of the play address different audience members in their various social roles, thereby reinforcing those roles, and not all audience members are being addressed at any one time…”. If any of you have [re-]watched media aimed at kids and suddenly get jokes you didn’t before, you have experienced interpellation. There are tons of pages dedicated to explaining these jokes aimed at adults nestled in works aimed at children (such as http://pixar.wikia.com/Adult_Humor or http://www.collegehumor.com/article/6900126/10-sexual-jokes-on-thesimpsons-you-mightve-missed-as-a-kid--I know the Simpsons, the greatest TV show in the history of humankind (and yes, I’m looking at you, Family Guy fans), is actually aimed at adults, but when it came out cartoons were thought to be for children only). Common Session assignment: This week I want to think about the implications of interpellation and humor. Some scholars don’t believe that Plautus is putting any humor for anyone except free citizen men in his work. I want you to play both sides of the fence. First, in 200-250 words, take a joke from Act 1, Scene 5, explain how it works differently for two populations (e.g. male/female, master/slave, citizen/foreign, poor/slave, poor/rich, etc.). Then respond to two other posts and explain how the humor actually super-secretly reinforces conventional Roman values and makes the citizen guys who have all the power feel better about themselves. Tuesday “Slavery” [Part 2] (Del Chrol, Marshall University) ppt presentaton Eighth Common Session (Nov. 5th) Latin reading: to Line 971 (1416) Common Session assignment: Read Casina ll. 207-557 Plautus' Casina tells the story of the old man Lysidamus who plots to marry off the slave girl Casina to his bailiff Olympio, a scheme that will allow him to keep Casina as a secret concubine for his own use. Lysidamus' wife Cleostrata, however, is rightfully suspicious of her husband's intentions, for Casina had been betrothed to their own son. They decide to settle the matter by casting lots. Lysidamus wins, and Casina is to be married off to Olympio. Cleostrata ultimately carries the day, however, by arranging for her own slave Chalinus to dress up as Casina so that Olympio winds up with a "bride" very different than the one he had imagined. Read the following scenes from Casina ll. 207-557, featuring: 1) initial exchanges between Cleostrata and her neighbor Myrrhina (a more dutiful wife); 2) comical banter between Cleostrata and Lysidamus; 3) the lot drawing scene; and 4) further conversations among Lysidamus, the bailiff Olympio, the slave Chalinus, and a neighbor Alcesimus. In Latin the word pietas denotes, among other things, what we might call in English "filial piety," a set of behaviors that demonstrate proper dutiful and respectful relations within the familial hierarchy. The subservience of the wife, the gravitas of the senex, the temperance of sons, and the chastity of daughters are the hallmarks of this quality. As you will have observed, subversions of pietas often provide the substance for comedy in Plautus. Although the actions of the slave Pseudolus demonstrate one kind of subversion, other Plautine plays showcase an even broader range of family dysfunctions. After reading the assigned text in English and at least glancing at some of the more interesting passages in Latin, please take 300-400 words and discuss the following: 1) How do these exchanges satirize idealized notions of marriage and family? Cite at least two specific passages where inversions of familial roles and powers lead to humor. Which lines work best and why? 2) Compare the characterization of Lysidamus and Simo. Cite and discuss one passage from the Pseudolus that brings to light one or more similarities. Tuesday “Bald Men and Battle Axes: Conjugal and Extra-conjugal Relations” (Heather Vincent, Eckerd College) Ninth Common Session (Nov. 12) Latin reading: to Line 1155 (1515) Common Session assignment: Read Terence, Eunuchus, in translation and synopses of Terence's five other plays: Andria, Hecyra, Phormio, Heautontimoroumenos, and Adelphoe Please take 300-400 words and discuss the following: The Eunuch was "the single most successful play ever staged in Roman history" (Parker 591, emphasis mine). It is also the only surviving play to contain a rape scene. Pay close attention to this element of the play. How is the rape portrayed in the Eunuch? What's the situation? Is the rape pre-meditated, or how does Chaerea get the idea to commit this crime? How do the other characters respond to the rape? What indications do we have that the attack was violent? For this week’s written assignment, consider the rape scene in the context of the definition of the comedic genre. One of the standard features of Roman comedies is that the social order is disrupted. For example, children are born out of wedlock, sons disappoint and disobey their fathers, citizen women are mistakenly sold into slavery, and family members get lost and separated after a shipwreck. The traditional happy ending, then, is the resolution of this disruption and the restoration of the social order. The child is discovered to be legitimate, sons win their fathers’ approval, the citizen women are rescued from their slavery, and family members are reunited. The ending of the Eunuch is peculiar. Does it follow this pattern of disruption and resolution? Does it have a happy ending, and if so, for whom is it happy (or maybe, how is it happy)? Tuesday “Terence: The Greatest Comic Playwright to Ever Live” (Heather Gruber, Concordia College) Tenth Common Session (Nov. 19th) Latin reading: to the end of the play (1613) Common Session assignment: Please read: 1) Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing, Act II sc. iii 2) Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest, Act I, beginning: Jack: Charming day it has been, Miss Fairfax. and concluding: Jack: Is that clever? 3) Joe Orton, What the Butler Saw, Act I, beginning to entrance of Dr. Rance, concluding: Rance: … I'd have sway over a rabbit hutch if the inmates were mentally disturbed. (pp. 363-376 of Joe Orton: Complete Plays) Please take 300-400 words and discuss the following: Through numerous cultural and performative permutations, New Comedy characters and structures have proved remarkably resilient and productive for the western history of comedy. Please read the assigned three scenes from outstanding comedies of the 16th (Shakespeare), 19th (Wilde), and 20th (Orton) centuries. Then respond to the following two questions (in 300-400 words): what changes particularly interest you in any of the stock character types of New Comedy as here represented, and what expectation do you have for the plot development of the play based on these characters? For the first, you may consider one, two, or all three of the plays, while for the latter I ask that you focus on one play in particular (and if you have seen or read the entirety of any of these plays, pick one that you do not know for your discussion of expected plot development). Tuesday “Hello, You Must Be Going” (Niall Slater, Emory University) NB: The Latin 391/291 common final exam will be available starting Thanksgiving break.