Arthur Asa Berger

advertisement

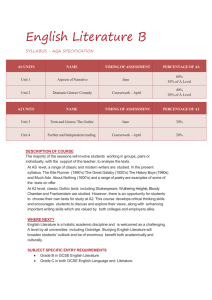

Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 1 As Barthes argued [in Mythologies], the themes of humanities earliest stories, known as myths, continue to permeate and inform pop culture’s story-telling efforts. As in the myths of Prometheus, Hercules, and other ancient heroes, Superman’s exploits revolve around a universal mythic theme—the struggle of Good and Evil. This is what makes Superman, or any action hero for that matter, so intuitively appealing to modern audiences….The word “myth” derives from the Greek mythos: “word,” “speech,” “tale of the gods.” It can be defined as a narrative in which the characters are gods, heroes, and mystical beings, in which the plot is about the origin of things or about metaphysical events in human life, and in which the setting is a metaphysical world juxtaposed against the real world. In the beginning stages of human cultures, myths functioned as genuine “narrative theories” of the world. That is why all cultures have created them to explain their origins….The use of mythic themes and elements in media representations has become so widespread that it is hardly noticed any longer, despite Barthes’ cogent warnings in the late 1950s. Implicit myths about the struggle for Good, of the need for heroes to lead us forward, and so on and so forth, constitute the narrative underpinnings of TV programmes, blockbuster movies, advertisements and commercials, and virtually anything that gets “media air time.” (2002:47-48) Marcel Danesi, Understanding Media Semiotics Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 2 Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story Speculations on Myth and Media Will the new electronic media lead to the end of reading? Will “old fashioned” print narratives become obsolete as legions of children and adolescent abandon comic books, stories and novels to spend all their time watching television and fiddling with Gameboys and various game-playing mini-supercomputers like the X-Box and Playstation? These questions might seem reasonable, since there has been an incredible rise in the popularity of video games, for example. But it is unlikely that we will abandon other “old” media and replace them with “new” media. Just as television didn’t destroy radio and radio didn’t destroy newspapers, video games are unlikely to turn print (and the narratives they carry) and other electronic media into niche media. One reason the “old” media will continue to flourish, I believe, is because they are full of narratives that do such a good job of providing us with modernized and camouflaged versions of ancient myths, of dealing with our need for living mythically. Narratives Pervade Our Media and Our Lives We have to make a distinction between stories, that is narratives, and the media that make these stories available to people. The fact is that narratives, of one Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 3 sort or another, pervade the media. For example, in his book The Age of Television, Martin Esslin estimated, in 1982, that the average male television viewer watched more than 12 hours of drama per week and the average female watched almost 16 hours of drama per week. The average American, he suggested, “sees the equivalent of five to six full length stage plays a week.” (1982:7) That’s because, he explains, television—the most popular medium—is essentially dramatic. He writes: (1982:7) One the most obvious level television is a dramatic medium simply because a large proportion of the material it transmits is in the form of traditional drama mimetically represented by actors and employing plot, dialogue, character, gesture, costume—the whole panoply of dramatic means of expression. If you look at television from the perspective of a dramatic critic, Esslin suggests, you can gain a better understanding of television’s essence as a dramatic medium (this applies to the cinema, as well) and various aspects of its social, psychological, and cultural impact. We swim, like fish, in a sea of narratives—or, to use Michel de Certeau’s metaphor, we walk, all day and every day, through a forest of narrativities. As de Certeau explains in The Practice of Everyday Life: (1984:186) From morning to night, narrations constantly haunt streets and buildings. They articulate our existences by teaching us what they must be. They "cover the event," that is to say, they make our legends (legenda, what is to be read and said) out of it. Captured by the radio (the voice is the law) as soon as he awakens, the listener walks all day long through the forest of narrativities from journalism, advertising, and television narrativities that still find time, as he is getting ready for bed, to slip a few final messages under the portals of sleep. Even more than the God told about by the theologians of earlier days, these stories have a providential and predestining function: they organize in advance our work, our celebrations, and even our dreams. Social Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 4 life multiplies the gestures and modes of behavior (im)printed by narrative models; it ceasely [sic] reproduces and accumulates "copies" of stories. Our society has become a recited society, in three senses: it is defined by stories (recits, the fables constituted by our advertising and informational media), by citations of stories, and by the interminable recitation of stories. We are, it seems, story-making and story-loving beings and these stories do more than amuse and entertain us—they teach us about life, they offer models to imitate, and they can, in some cases, reinforce our battered egos. There is good reason, then, why narratives are so dear to us. Narratives, of every genre, pervade our lives—from the conversations we have with friends to the television dramas and films we watch. It is narratives that teach us about the Devil and about God and everything in between. It would not be too far removed to suggest that in addition to being homo ludens we are also homo narratus—story telling men and women. I will deal with a number of aspects of narratives here: narratives and fairy tales, narratives and genres, narratives and myth, the gratifications genres provide, and narrative genres and myths. I will suggest that, in essence, all stories are variations on the narratives that we find so intoxicating when we are young—fairy tales. I will consider the formulaic aspects of genres and also argue that generally speaking there is a mythic element hidden in our stories of all kinds: in the elite arts, in popular culture, and in everyday life, because although we think logically, we live mythically. Defining Genres Fairy tales, we must remember, are a kind of story—or in the language of media criticism, a genre, a French word that means “kind” or “type.” In his essay “Television Images, Codes and Messages, “ Douglas Kellner discusses genres and their role in our mass-mediated culture: Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 5 A genre consists of a coded set of formulas and conventions which indicate a culturally accepted way or organizing material into distinct patterns. Once established, genres dictate the basic conditions of cultural production and reception. For example, crime dramas invariably have a violent crime, a search for its perpetrators, and often a chase, fight, or bloody elimination of the criminal, communicating the message “crime does not pay.” The audience comes to expect these predictable pleasures and a crime drama “code” develops, enshrined in production and studio texts and practices. (Televisions, 7, 4, 1974) These conventions make is easy for audiences to understand what happens in a text and easier for writers to create these texts, since they can assume certain expectations on the part of audiences and use formulas, with minor variations, to satisfy these expectations. In our everyday lives, we often make our decisions about what kinds of television shows to watch, films to see, or video games to play, based on how we may feel or upon certain attractions a genre holds for us. And we decide to watch certain television programs or go to certain films because, in part, of the pleasures the genre has for us. For complicated reasons, that I will discuss later, people develop a fondness for certain kinds of stories. When we are children, fairy tales are very important for us, because, as Bruno Bettelheim has explained in The Uses of Enchantment, fairy tales have great therapeutic value for children. When we are older and more complicated beings, we move on to more complicated kinds of stories, with different kinds of characters that provide different kinds of gratifications. Gratifications Genres Provide Let me offer, here, a chart listing of some of the more important gratifications genres provide audiences. The “Uses and Gratifications” approach to mass mediated texts focuses on the social uses audiences make of the texts they see and the Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 6 psychological gratifications these texts provide, as contrasted with a focus on the effects of exposure to texts and genres. Some of the earliest research in this area was described as follows by Katz, Blumler and Gurevich (1979:215): Herzog (1942) on quiz programs and the gratifications derived from listening to soap operas; Suchman (1942) on the motives for getting interested in serious music on radio; Wolfe and Fiske (1949) on the development of children’s interest in comics…Each of these investigations came up with a list of functions served either by some specific contents or some medium in question: to match one’s wits against others, to get information or advice for daily living, to provide a framework for one’s day, to prepare oneself cultural for the demands of upward mobility, or to be reassured about the dignity and usefulness of one’s role. In my chart I deal with genres rather than with individual texts and suggest the various uses and gratifications genres provide. Uses and Gratifications Genres To satisfy curiosity and be informed To be amused Documentaries, News Shows, Talk Shows, Quiz Shows Situation Comedies, Comedy Shows To identify with the deity and divine Religious Shows To reinforce belief in justice Police Shows, Law Shows To reinforce belief in romantic love Romance novels, Soap operas To participate vicariously in history Media Events, Sports Shows To see villains in action Police Shows, Action-Adventure Shows To obtain outlets for sexual drives in a guilt free context Pornography, Fashion Shows, Soft Core Commercials, Soap Operas Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 7 To experience the ugly Horror shows To find models to imitate Talk Shows, Action Shows, Award Shows, Sports Shows, Commercials Travel Shows, Art Shows, Culture Shows (Symphony Concerts, Operas, Ballet) To experience the beautiful One of the difficulties of the uses and gratifications approach is that it is very difficult to quantify the uses people make of genres and tie events in a given text to this or that gratification. Nevertheless, it is quite obvious that people listened to radio soap operas (the subject of the study mentioned above by Herta Herzog) and watch soap operas on television because they provide a number of gratifications to their viewers. The Fairy Tale as the UR-Genre I have suggested, in my book Narratives in Popular Culture, Media and Everyday Life, that we see the fairy tale as an UR-genre. In a typical fairy tale you might find monsters and other kinds of strange creatures (horror), someone searching for a missing damsel in distress (detective), someone flying on magic carpets (science fiction), someone fighting villains or opponents of one sort or another (actionadventure hero), and a hero marrying a princess he has rescued (romance). The basic genres, can be seen then, as spin-offs emphasizing different aspects of the typical fairy tale…and, as I shall argue, certain myths. In the chart that follows I offer suggestions about that formulaic aspects of some important genres: the kinds of characters we find in them, their plots and their themes, and so on. Thinking about stories in terms of their formulas, and what happens in certain genres, helps us understand something about their appeal. This chart shows some of the basic conventions found in formulaic genres. These conventions establish what a genre means for people and enable them to understand the texts without too much expenditure of intellectual effort. Of course some works in a given genre are more formulaic than others; there is some latitude within genres for experimentation, but most mass mediated texts tend to be formulaic. Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 8 I assume that people learn the conventions of various genres as they are exposed to them. Genre Romance Western Science-Fiction Spy Time Early 1900s 1800s Future Present Location Rural England Outer Space World Hero Lords, Upper Class Types Damsel in Distress Friends of Heroine Lying Seeming Friend Heroine Finds Love Love Conquers All Gorgeous Dresses Cars, Horses, Carriages Fists Edge of Civilization Cowboy Space Man Agent Schoolmarm Space Gal Woman Spy Town people Indians Outlaws Technicians Assistant Agents Aliens Moles Restore Law and Order Justice and Progress Cowboy Hat Repel Aliens Find Moles Save Humanity Space Gear Save Free World Trench Coat Horse Rocket Ship Sports Car Six-Gun Ray Gun Laser Gun Pistol with Silencer Heroine Secondary Villains Plot Theme Costume Locomotion Weaponry Genres also come and go. At one time, in the seventies in the United States, there were more than thirty westerns being broadcast on television each week, and numerous western films. In contemporary America, there are few westerns being made for television or film. This is probably because the conventions of the genre no longer resonate with Americans and because other genres have evolved that do a better job of providing the gratifications people are looking for from media. Let me offer a case study here, on the romance genre. I take my point of departure with Janice Radway’s excellent book, Reading the Romance Romance Novels and Their Readers: A Case Study. Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 9 What, exactly, is a romance and what are its characteristics? How do romances differ from other narrative texts? To answer this question, Radway offers what is essentially “a Proppian analysis of the romantic plot.” (1991:120) She asked some romance readers she knew for a list of their favorite romances and with twenty of these books in hand, examined them “to determine whether the same sequence of narrative functions can be found in each of these texts.” She adds a qualifier to her Proppian analysis: (1991:120) …a genre is never defined solely by its constitutive set of functions but by interaction between characters and by their development as individuals. As a result, I have assumed further that the romantic genre is additionally defined for the women by a set of characters whose personalities and behaviors can be “coded” or summarized through the course of the reading process in specific ways…By pursuing similarities in the behaviors of these characters and by attempting to understand what those behaviors signify to these readers, I have sought to avoid summarizing them according to my own beliefs about and standards for gender behavior. She summarizes the narrative structure of the typical romance as follows: Romances start with a heroine being removed from her family and familiar surroundings; this is an example of Propp’s first function, absentation. Other aspects of the formula correspond to variations of one sort or another of Propp’s 31 functions, including recognition, when the heroine’s goodness and beauty are recognized by the hero, and wedding, when the heroine is (or will soon be) married. What Radway’s analysis suggests is that the romance novel is a highly formulaic genre or kind of text, generally involving the theme of changing of male behavior (and what woman doesn’t want to do that?) from indifference to love, with a number of formulaic sub-genres that vary on the basic romance formula one way or another. Taking a formula--a simple set of basic behaviors or Proppian functions-romance writers have been able to write an incredible number of romances. In effect, Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 10 we can say about these romance novels that they all are “the same old story,” just told in different ways with slightly different stereotyped characters plugged in at the relevant points. Actually, we can say the same thing about most texts and genres in the mass media. Many genres have sub-genres. For example, the detective genre has three sub-genres: the classical detective story with a detective who uses his or her brains (Sherlock Holmes, Hercules Poirot, Miss Marple), the tough guy detective story with a hero who is smart but also who is good with his fists (Sam Space, Mike Hammer) and the procedural detective story (CSI). It has been suggested by Will Wright, in Sixguns and Society: A Structural Study of the Western, that there are four sub-genres of westerns and many other genres have a goodly number of sub-genres, as well. At the conclusion of her book, Radway offers some insights about the power individuals and groups of readers have to resist the power of those who control the media. She writes: (1991:222) If we can learn, then, to look at the ways in which various groups appropriate and use the mass-produced art of our culture, I suspect we may well begin to understand that although the ideological power of contemporary cultural forms is enormous, indeed sometimes even frightening, that power is not yet all-pervasive, totally vigilant, or complete. Interstices still exist with the social fabric where opposition is carried on by people who are not satisfied by their place within it or by the restricted material and emotional rewards that accompany it. There are, Radway suggests, good reasons to believe that, for one reason or another (including the fact that people often don’t interpret texts the way those who create them think they will) people can resist the power of the media. I need only mention what happened in the countries in eastern Europe dominated by Russia. As soon as people in these countries discovered that the Red Army would not invade them if they Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 11 threw out the people who were ruling them, despite forty years of media propaganda, they did so with hardly a second thought. The Myth Model I have suggested, in a number of my writings, that texts of all sorts—in the elite arts and in popular culture—often have mythic roots. I developed what I describe as a “myth model” that follows a myth in history, elite culture, popular culture and everyday life. I got this notion from Mircea Eliade, who explained in The Sacred and The Profane that many things that people do in contemporary society are actually camouflaged or modernized versions of ancient myths and legends. As Eliade writes: (1961:204-205) The modern man who feels and claims that he is nonreligious still retains a large stock of camouflaged myths and degenerated rituals…A whole volume could well be written on the myths of modern man, on the mythologies camouflaged in the plays that he enjoys, in the books that he reads. The cinema, that “dream factory,” takes over and employs countless mythological motifs—the fight between hero and monster, inititatory combats and ordeals, paradigmatic figures (the maiden, the hero, the paradisal landscape, hell, and so on). Even reading includes a mythological function, not only because it replaces the recitation of myths in archaic societies and the oral literature that still lives in the rural communities of Europe, but particularly because, through reading, the modern man succeeds in obtaining an “escape from time” comparable to the “emergence from time” effected by myths. Eliade defines myth, I should add, as the recitation of a sacred history, “a primordial event that took place at the beginning of time.” (1961:95). Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 12 We find a more elaborated definition of myth in Raphael Patai’s Myth and Modern Man. He describes myth in the following terms ( 1972:2) Myth…is a traditional religious charter, which operates by validating laws, customs, rites, institutions and beliefs, or explaining socio-cultural situations and natural phenomena, and taking the form of stories, believed to be true, about divine beings and heroes. He adds that myths play a an important role in shaping social life and that “myth not only validates or authorizes customs, rites, institutions, beliefs, and so forth, but frequently is directly responsible for creating them.” (1972:2). Let me offer, here, my myth model. My argument, based on Eliade’s point about unrecognized myths permeating our culture and Patai’s notion that myths help shape culture, suggests that there are camouflaged and unrecognized myths that inform many texts and other aspects of our culture. People who watch films and television shows, go to operas and ballet, and do various things as part of their everyday lives, generally don’t realize the extent to which myth informs all these activities. The implication is that when we read novels, watch televised dramas and go to plays and films, we are connecting to ancient myths and thus, through these entertainments, we live mythically, even if we may not recognize that such is the case. In the chart below, I take several myths (sacred stories) and run them through my model. Myth/Sacred Story Adam in the Garden of Eden. Theme of Natural Innocence Oedipus Myth. Theme of son unknowingly killing father and marrying mother. Revolutions Historical Experience Puritans come to USA to escape corrupt European civilization Elite Culture American Adam figure in American novels. Henry James’ The American Sophocles, Oedipus Rex Shakespeare, Hamlet Popular Culture Westerns…restore natural innocence to Virgin Land. Jack the Giant Killer Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 13 Shane. Everyday Life Escape from city and Oedipus period in little move to suburbs so kids children can play on grass (and with grass). What this model does is show the hidden sacred or mythic roots of many different aspects of our lives. Thus, in America, where nature is an important part of the American imagination—perhaps the most important element in it--manifestations of the biblical story of Adam and Eve, living in paradise in a state of nature, can be found in everything from our historical experience—leaving “corrupt” Europe to establish a new utopian society in the great American wilderness—to our elite literature, with its American Adam figures in many novels, to our westerns and science fiction stories and our moving to the suburbs. Our popular culture texts, such as Westerns, often deal with getting rid of evil doers and villains, of one sort or another, so that, in theory at least, a more paradisal society can be re-established again in nature. In a seminar I taught on popular culture a number of years ago I gave my students the myth model and the Adamic myth and asked them to play with it. They provided some of the answers found in my chart. When someone suggested that moving to the suburbs was probably connected to this myth one of my students, a woman in her mid thirties with two children, slapped head and said “So that’s why I moved to the Mill Valley” (a suburb of San Francisco, where I happen to live)! The Nature Myth and American Identity In the American imagination, I would argue, we have traditionally seen ourselves as living in a state of nature, and contrasting that with our motherland and fatherland Europe, which we identify with civilization and its various discontents. We can see this in the chart below, which deals with the way we have defined ourselves, in the best de Saussurean tradition, as un-Europeans in the same way that 7-Up has Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 14 defined itself as the “un-cola.” I’m not suggesting that this set of oppositions is correct, only that is the way we have defined ourselves for many years…and perhaps still do. America Europe Nature History Innocence Guilt Individualism Conformity The Future The Past Hope Memory Forests Cathedrals Cowboy Cavalier Willpower Class Conflict Equality Hierarchy (Aristocracy) Achievement Ascription Classless Society Class-Bound Society Nature Food, Raw Food Gourmet Food Clean Living Sensuality Action Theory Agrarianism Industrialism The Sacred The Profane My chart, though it may have little basis in reality, does reflect the way Americans tended to see themselves as they tried to find an identity and did so by contrasting themselves with a simplistic and stereotyped image of Europe. The United States is not a classless society, even though many people living in America tend to think it is…with, we used to describe as small “pockets” of poverty and a small number of rich people. We had no hereditary aristocracy so we’ve tended to Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 15 downplay the extent to which America has (and always had) different classes. In recent years, however, as the split between the rich and the poor grows greater, more and more people are becoming aware of the existence of social classes…and of a new celibritocracy of athletes, movie stars and other kinds of entertainers, some of whom are worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Genres and Myths I believe that, among other things, if you scratch deep enough beneath the “surface” of a text you can generally find a myth—a kind of intertextuality that may explain one of the reasons that certain texts resonate with us. Freud made this point in his famous letter about Oedipus Rex. As he wrote, in his famous letter of October 15, 1897 to Wilhelm Fleiss: Being entirely honest with oneself is a good exercise. Only one idea of generally value has occurred to me. I have found love of the mother and jealousy of the father in my own case too, and now believe it to be a general phenomena of early childhood, even if it does not always occurs so early as in children who have been made hysterics…If that is the case, the gripping power of Oedipus Rex, in spite of all the rational objections to the inexorable fate that the story presupposes, becomes intelligible, and one can understand why later fate dramas were such failures. Our feelings rise against any arbitrary individual fate…but the Greek myth seizes on a compulsion which everyone recognizes because he has felt traces of it in himself. Every member of the audience was once a budding Oedipus in fantasy and this dream-fulfillment played out in reality causes everyone to recoil in horror, with the full measure of repression which separates his infantile from his present state. The idea has passed through my head that the same thing may lie at the root of Hamlet. I am not thinking of Shakespeare’s conscious intentions, Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 16 but supposing rather that her was impelled to write it by a real event because his own unconscious understood that of his hero…. What Freud is suggesting about Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex and Shakespeare’s Hamlet, I believe, applies—though we don’t realize it--to many aspects of our daily lives, to texts in elite and popular culture, and, of particular interest, to the genres in which we find these texts that entertain us. In many cases the myth is modified and defanged— weakened and camouflaged, lest it show through and, in some cases, be too disturbing to readers and audiences of mass mediated genres. I have suggested that not only texts have mythic content but also the genres in which we find these texts, and it may be that a given genre has an appeal that we do not recognize, assuming that it is the text and only the text that is important. If Shane is mythic that may be because the Western genre is mythic, too. In the chart that follows, I list some of the more important genres that draw upon certain myths—a highly speculative enterprise, I admit. A given text becomes, then, an intermediary between a genre and a myth. In some cases, we choose a particular text (film, television show) because of the genre and in other cases we choose the genre because of a certain text. Genre Myth Western Garden of Eden Science Fiction Ezekiel’s Vision in Bible Action Adventure Hercules, Odysseus Soap Opera Sisyphus Beauty Contests Narcissus Space Opera Icarus Horror Lilith, Medea, Minotaur Love and Romance Helen of Troy, Pygmalion Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 17 War and Combat David and Goliath It is reasonable to suggest, then, that there are a relatively limited number of myths, from the Greeks and Romans and the Bible, along with a number of other cultures and sources, which can be described as “cultural dominants” that have shaped our consciousness in the West over the millennia. Think, for example, of the impact that the story of Adam and Even in Paradise (and their eating from the tree of knowledge and being expelled from The Garden of Eden) has had. My myth model makes a case for the notion that we may live “modern,” in a logical-rational-scientific world, or even in a postmodern world where people experience “incredulity toward metanarratives,” but we act and believe mythically, thanks, to a large degree, to the narratives and genres in the media that entertain us and, at the same time, connect us in ways we are only now beginning to realize, to ancient myths. A Postscript In the chart that follows, taken from my forthcoming book, tentatively titled Making Sense of Media: Key Texts in Media Analysis and Cultural Studies (Blackwell, 2004) I offer my readers an opportunity to write their own romance novels. My chart on the formulaic aspects of genres, let me point out, was also taken from this book. All you have to do is take items from any of the four columns at the first level and mix them with any items from the four columns at the second level (making whatever minor modifications may be necessary) and keep doing this until you have exhausted all the levels. Then you just have to write it up as a novel and send it off to an agent and wait for the money to start rolling in. Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 18 Write Your Own Romance Daphne Witherspoon Found Herself Abandoned and Far Away From Home and In Her Darkest Hour Met 1 2 3 4 Lord Randall Cuthbert Riding on his great white steed Palomar Slade Slick, a riverboat gambler and smoothie, with greased black hair and a drooping mustache. His teeth were bad, also. The Reverend Amos Homer, a prairie riding minister from The Church of the Faithful. He was very handsome in his clerical outfit. Dr. Lance Hobbes, a neurologist, world famous mountain climber, and writer of important novels and books on sports and on psychology. Who treated her with scorn, thinking her to be a wanton woman from the lower classes Who was very kind to her, but only, she thought, because he wanted to have sexual relations with her…as with all women he knew Who was hostile and said she seemed to be an unbeliever who needed to be saved. He wanted to convert her to his faith and teach her to speak in tongues. Who said he noticed a slight facial tic, a sign of serious problems. He wanted to take her mountain climbing in Tibet to help solve her problems. Then he noticed that she had a 38 inch bust, gorgeous legs, long blonde hair and sparkling blue eyes Then he said he could find her a nice place to stay in a place near Las Vegas. “The work isn’t very hard,” he said. You just lie around in bed most of the time. But she recognized his evil nature and told him she didn’t like Las Vegas, or Reno, for that matter. Then he said she needed special attention and said she should meet him at a certain church at midnight. Then he decided she was too frail to take mountain climbing, but he noticed her great beauty…her 38 inch bust and long blonde hair and sparking eyes But she told him she wouldn’t do that because she had lost her faith in man and in God, having been abandoned by a man she thought she would marry. Then she noticed that he was tall, dark and strikingly handsome, and drove a Maserati. She could tell he came from noble stock. Then he told her she had stolen his heart, he apologized for his callous treatment of her and declared his undying love for her. Then he asked her whether she had any sisters or friends who looked like her and who were out of work. Then he said she lacked “the gift of faith” but he could save her. He added that his church allowed many wives and he proposed to her. Then she noticed that he had a wonderful sense of humor besides being clever and enormously wealthy. So she became Lady Cuthbert, moved to England to live in a great mansion. Their love grew deeper At this point she told her to speak with Rev. Homer Nesbitt, who could save his soul. She decided to But she rejected him saying she believed in monogamy. He decided to get an MBA and marry a So she became Mrs. Hobbes. They bought a palatial house in Los Angeles and he gave her a So, he got into a conversation with her and discovered she was very smart and witty. She noticed that he was very handsome. Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 19 with every day. Hollywood and become a star and find true love. clever executive and live happily ever after. Bibliography Berger, Arthur Asa. 1992 Popular Culture Genres: Theories and Texts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Berger, Arthur Asa 1997 Narratives in Popular Culture, Media and Everyday Life Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Berger, Arthur Asa. 1998. Media Analysis Techniques (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Berger, Arthur Asa. 2003 Ads, Fads, & Consumer Culture (2nd Edition) Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Berger, Arthur Asa. 2003 Media & Society Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Eliade, Mircea. 1961 The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion Rolls Royce as a symbol of his undying love Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 20 New York: Harper Torchbooks Danesi, Marcel. 2002 Understanding Media Semiotics London: Arnold de Certeau, Michel. 1984 The Practice of Everyday Life Berkeley: University of California Press Kellner, Douglas. 1980 “Television Images, Codes and Messages” Televisions 7 (4) 1974 Patai, Raphael. 1972 Myth and Modern Man Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Radway, Janice. 1991 Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press Wright, Will. 1975 Sixguns and Society: A Structural Study of the Western. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press Arthur Asa Berger The Same Old Story 21 Arthur Asa Berger is professor emeritus of Broadcast & Electronic Communication Arts at San Francisco State University, where he taught from 1965 to 2003. Among his recent books are Bloom’s Morning: Coffee, Comforters, and the Secret Meaning of Everyday Life (Westview), Durkheim is Dead: Sherlock Holmes is Introduced to Sociological Theory (AltaMira Press), and The Agent in the Agency (Hampton).