Peak Oil Summary

advertisement

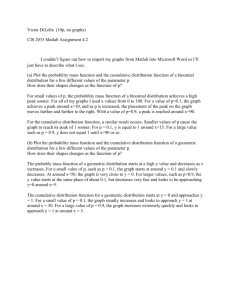

Peak Oil Will there be a downturn in global oil production soon? Peak Oil is the time when the rate of oil production worldwide starts its inevitable decline. It is widely forecast to occur sometime around 2014 (+/-5 years). We will probably not know when oil production reached its all-time maximum until some years after the event. As well there are differing definitions and estimates of oil production, so there is considerable uncertainty about the data behind the forecasts. Others are much more optimistic, but are they now in the minority. There have been a number of very authoritative and important reports warning about Peak Oil or oil scarcity. Nature (the world’s premier science weekly), The International Monetary Fund, Macquarie Bank, Lloyds of London, the US Defence Department, BITRE (Australia’s Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics) and Sir Richard Branson have all warned about oil shortages in the near term. The International Energy Agency (IEA) was established by the oilconsuming nations to counterbalance the OPEC cartel, and in the past it has been very optimistic about future oil production rates. It has been criticised by a whistleblower for caving in to US pressure to understate the problem, and by the Global Energy Systems group in Sweden for using unrealistically over-optimist production-rates in its forecasts. However, the IEA has been increasingly strident in its warnings about declining production rates in the world’s currently producing oilfields, and it has been continually revising downwards its estimates of forward oil production. Of course, there are other views, for example from CERA and ExxonMobil, that there is no peak in sight. However, the growing body of evidence from a wide range of sources is certainly reason to consider very seriously the possibility that Peak Oil will occur within the next few years. Oil rose from $14/bbl in July 1998 to reach $145/barrel in July 2008 before falling briefly to $30 as a result of the global financial crisis then rising again steeply to almost pre-GFC levels. How long before it rises sharply again and reaches $200 or $300? We don't know, but Peak Oil will probably arrive soon; when world oil production starts its geologically-determined decline while demand ASPO-Australia July 2011 1 continues to rise. CSIRO's Future Fuel Forum economic modelling has a worst-case scenario of $8/litre for transport fuel in Australia by 2018 if Peak Oil occurs soon, and if alternatives like largescale coal-to-liquids and gas-to-liquids are not on stream then. The majority of world's giant oilfields are already in decline now. As a local example, Bass Strait started its decline in 1985 and is now producing only a tiny fraction of its peak yield. Australia's overall oil production peaked in 2000 and is going downhill fast. In its comprehensive World Energy Outlook in November 2008, the IEA released results of a unique analysis of 800 oilfields, including all 54 super-giants (> 5 Gbbl) in production today. It estimates that the average production-weighted decline rate worldwide for fields that have passed their production peak is currently 6.7% p.a., and this is expected to increase to 8.6% p.a. in 2030. This means that fresh sources of oil producing a total of 45 million barrels a day (over half the world's current production) will have be found simply to maintain present levels of supply to 2030. IEA Chief Economist, Dr Fatih Birol, is often interviewed by the world media, and he reiterates the same warning as reported here. "The world is heading for a catastrophic energy crunch that could cripple a global economic recovery because most of the major oil fields in the world have passed their peak production" The IEA estimates of future production have been reviewed by Prof Aleklett of the Global Energy Systems group at the University of Uppsala in Sweden. Using the same basic data of decline rates of existing fields and reserves in the “yet-to-be-developed” and “yet-to-find” categories, the Uppsala group forecast very considerably lower production rates out to 2030. They discovered that the IEA had assumed unrealistically high production rates from the reserves in the new fields, twice as high as has ever been achieved in any oil region, even high-tech areas like the North Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. This, and some other more minor differences, led Prof Aleklett to estimate a global production rate, based on the same IEA data, of 75 mb/day in 2030, compared to the IEA’s 106 mb/day, which is 41% higher than the Uppsala group’s forecast. As illustrated in the IEA forecasts, declining production in existing fields will be offset in part from production from fields already discovered and being brought on-stream, and from fields yet to be discovered. The near-term production from fields already discovered can be estimated from published information on existing and proposed projects. The “Megaprojects” approach was pioneered by Chris Skrebowski when he was Editor of the Petroleum Review, published by the Institute of Energy in London. A field discovered next year may not be producing at capacity for perhaps a decade, so the near-term production can be estimated from existing production rates, the average 6.7% p.a. or thereabouts decline rate and ASPO-Australia July 2011 2 importantly from the expected contributions from fields now being brought into production. Estimating these new projects, or expansion to existing fields is the basis of the Megaprojects approach. In his presentation to the ASPO-9 conference in Brussels in April 2011, Chris Skrebowski forecast a production crunch in 2012 or 2013; (the slides and video of his lecture are available at www.ASPO9.be ) His summary was that supply is tightening and future supply looks inadequate; uncertainty is discouraging investment and costs are rising; demand remains strong and is possibly underestimated; global oil stocks are trending down and the crunch point is no later than 2012/2013 As well as planning for Peak Oil, Australia should also be preparing for sudden oil shocks, bigger than the 1973 and 1979 oil crises. A revolution in Saudi Arabia or a war over Iran, for instance, would cause a dramatic global oil crisis. Contingency planning is recommended for say a 30% shortfall of transport fuels for three months or more (analogous to WA's 2008 Varanus Island natural gas shortage). The natural gas shortage was handled by constraining big industrial users in WA without any significant impact on ordinary people. However, a 30% petrol and diesel shortage would hit Australians much harder than the gas shortage hit WA. Australian oil price forecasts by ABARE economists have proved consistently wrong, as shown in the following graph, so relying on economists' forecasts is very unwise. Oil Prices (WTI monthly average) and Australian Government economists’ forecasts The Australian Financial Review reported the Nobel Economics prize-winner, Prof Vernon Smith in November 2005, when the oil price was $60/bbl. "ASPO's oil peak predictions are "baloney", an economic fallacy. According to Smith, a world about to reach an oil peak would be charging a lot more for oil, which he expects to sell for $15 a barrel in the near future". ASPO-Australia July 2011 3 Economic forecasts of oil prices and oil supply have been very frequently wrong. The recent article in Nature (481 433-435) shows an abrupt change in oil economics in about 2005, when increasing price has no longer sparked increasing production Showing the abrupt change in trend of production vs. price world when the plateau production phase was reached in 2005 Governments, communities and investors should be aware of the probability of future oil scarcity. Too many organisations, including superannuation funds, are investing in tunnels, toll-roads, airports and the like, which will prove very unwise when oil shortages occur. Peak Oil will certainly mean peak car traffic and peak airline travel. Ordinary people and small businesses are ASPO-Australia July 2011 4 making long-term plans on the assumption that fuel availability and travel patterns will remain the same as they are now. This is also unwise There are innumerable options for Peak Oil mitigation and adaptation. Many are "No-Regrets" alternatives; things we should be doing now. Many need to be started 20 years before Peak Oil arrives. We all need to start planning and acting now, as a matter of urgency, both for sudden fuel shortages and for the permanent shortages which will happen when Peak Oil arrives. Currently governments, economists, investors and the community are turning a blind eye to the probability that business in the oil industry will soon not be as usual and that serious shortages and on-going scarcity are very likely within a few years. "Peak Oil Policy Options for Australia", an invited paper presented in the Brussels ASPO conference in April 2011, outlines some of the social sciences options available to us. www.aspo-australia.org.au/References/Bruce/Peak-Oil-Policy-Options-for-Australia-Robinson-F3f.doc Bruce Robinson is convenor of the Australian Association for the Study of Peak Oil, a nationwide volunteer-based network of professionals working to warn Australia of its oil vulnerability. ASPOAustralia is keen to assist organisations and government with oil vulnerability assessments and risk management plans to prepare for probable near-term oil shortages. www.ASPO-Australia.org.au ASPO-Australia July 2011 5