Module 14 DOC

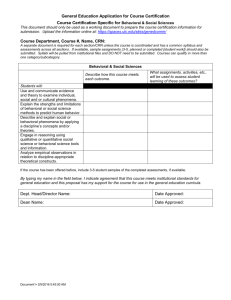

advertisement

Community Care of North Carolina: Model of Primary Care and Behavioral Health Integration This module will illustrate how Community Care of North Carolina has proposed the integration of behavioral health services into the primary care setting. The Behavioral Health Integration Initiative (BHI) supports the integration of behavioral health services, including services for mental health, substance abuse, and the intellectual/developmentally disabled consumers, into the 1,400 primary care practices/medical homes participating in the fourteen Community Care Networks across North Carolina. Each local network has hired psychiatrists and behavioral health co-coordinators to implement the proposal at the network and local levels thus establishing an appropriate workforce. The strength of the CCNC program has always been that initiatives are supported by local providers, recognizing the unique needs in each region and in each network. This enables them to address these unique needs utilizing a local response supported and guided by the local leadership of primary care physicians and behavioral health providers. It should be noted that the role of the network psychiatrist is not to provide direct care, but to serve as a liaison between the primary care providers and the local behavioral health system, thus supporting local integration of care. The network psychiatrist focuses on educating and cross training in both the primary care setting and the behavioral health specialty network. The Community Care networks can then serve as the medical home and central point of care for patients with mild to moderate behavioral health issues in the primary care system, as well as provide support for severe and persistent mentally ill patients in our specialty behavioral health system Why Integration of Care? The separation between primary care and behavior health care has evolved over many years through interpretations of confidentiality guidelines, issues of stigma, managed care carve-out programs, and inadequate benefit coverage for behavioral health treatments, among other issues. It has become increasingly evident that this “silo system of care” not only provides little to no coordination of care, but it also is dangerous for the patients we serve. We can no longer support a care model that ignores the reality that patients frequently have mental and physical co-morbidity factors. It is critical that barriers to coordinated care be eliminated to allow for a full exchange of information that can help ensure the safe management of both medical and behavioral conditions. The need to share information regarding the use of medications with potentially serious interactions (e.g., pain medications and benzodiazepines) along with the awareness of side effects that must be carefully monitored (e.g., metabolic syndrome) are crucial to best practice models of care. It is estimated that up to 70 percent of primary care visits involve a psychosocial component affecting the patient’s physical health. Further, reports indicate that up to 63 percent of psychotropic medications are prescribed by primary care physicians. It should be noted here that closer examination suggests primary care physicians continue the vast majority of those medications (especially the antipsychotics) after a psychiatrist has written the initial prescription with no opportunity for follow-up in a psychiatric setting. As man primary care physicians are hesitant to discontinue antipsychotic medications, patients often remain on these medications long after a reevaluation should have occurred. The goals of supporting integrated care in North Carolina are to focus on early identification through screening, provision of brief intervention programs with treatment when appropriate, and support for referral to treatment when a significant behavioral health condition is identified. What are the Models of Integrated Care? In a report by Community Care leaders and supported by the Milbank Foundation in 2010, eight models of integrated care are explained. The report can be viewed at http://www.milbank.org/reports/10430EvolvingCare/EvolvingCare.pdf. This report describes various models of care that reflect the individual characteristics of the region and the practice in determining a best approach to the integration of services. While it is not necessary to “progress” along a continuum to achieve integration, it is possible to initiate any one of these models based on local resources and practice patterns. This report describes the simplest forms of integration (collaboration among providers) to a completely integrated system of care. Role of the Network Psychiatrist In the partial job description below, some of the expectations for the network psychiatrists are described: The network psychiatrist will serve as the primary lead for the behavioral health integration (BHI) project and will serve as a collaborator with physical and behavioral health providers and other stakeholders in the local communities. He/she will be the lead mental health champion to advocate for the implementation of evidence-based practices for integrated care in primary care settings. Under the leadership of the lead psychiatrist, the BHI initiative will aim to do the following: Create a local work group that will be responsible for designing and planning a BHI model to be implemented in the network. Identify evidence-based guidelines applicable to enhanced medical homes, in concert with the Community Care central office behavioral health team. Educate and train, as needed, the primary care providers and community-based behavioral health providers. Work with the network leadership to build capacity at the primary care level to identify and treat patients’ behavioral health needs with evidence-based care. Develop processes for mentoring and communicating with network and central office leadership. Establish an evaluation process and plan that will document the local BHI program’s impact on quality, utilization, and cost, in concert with other MHI network and central office leaders. Work collaboratively with network leadership staff on Community Care core areas of emphasis (e.g., pharmacy, palliative care, transitional care) and produce coordinated programs that integrate mental health into ongoing and future projects and initiatives. An initial survey of primary care physicians (PCPs) was done in an effort to focus on the needs identified by the PCPs. The areas identified indicated a need for basic knowledge of the behavioral health system: access, collaboration, and crisis services. In the Behavioral Health Integration program in Community Care, it was evident that most primary care practices had very limited knowledge of the behavioral health system in their region. Referral into the behavioral health system was often described as a “black hole” where information went in, but little information came out. Consistent with the job description of the network psychiatrist and the behavioral health coordinator, local resources were identified, presentations from behavioral health providers were encouraged (lunch-and-learn programs), access to crisis services (including mobile crisis teams able to be dispatched to PCP offices) was identified. The main goal of this initiative was to develop collaborative relationships at the local level to begin the process of coordination of care between the two systems with the hope of increasing integration of services as local relationships developed. Training on the Informatics Center and the Provider Portal for the network psychiatrists will continue to enhance their knowledge and skill in working with available data from Pharmacy Home, the Case Management Information System and the Medicaid claims system. The utilization of this data will help identify practices and providers as well as individual cases that will receive intervention from case management and/or psychiatric input in an effort to improve the quality of care. The network psychiatrist’s role in the education on best practice models of care will be described as each initiative is discussed later in the module. The driving principles of the integration program are: early identification of developing issues through regular screenings (PHQ-2/9, SBIRT and child adolescent screens); brief treatments in the PCP setting, where appropriate (SBIRT, depression guides); and referral to a known behavioral health system if the condition or diagnosis warrants. Role of the Behavioral Health Coordinators The behavioral health coordinators in each network work closely with the network psychiatrist in helping set priorities for practice interventions, identify priority populations and identify complex cases for discussion in case management meetings. These coordinators are generally full-time employees who are licensed behavioral health professionals or registered nurses, and have experience with behavioral health patients. They serve as the liaisons between the psychiatrists (often employed part-time) and the network case managers who provide case management for the behavioral health population in the Community Care system. The behavioral health coordinators will often use data from the Informatics Center to identify high-risk populations or practices that appear as outliers in order to discuss appropriate interventions with the psychiatrist and the behavioral team. The behavioral health coordinators form the backbone of the Community Care BHI program and serve as a driving force in the integration efforts. Toolkit for Network Psychiatrists The goal of the integrated care program is to provide primary care physicians with tools to better identify and treat, to their level of comfort, behavioral health conditions. When the condition exceeds the brief treatment models of primary care, the PCP should be able to recognize the need to refer to an appropriate behavioral health resource within the specialty behavioral health system. It is the task of the network psychiatrist to offer and educate the PCP on a range of tools for training practices in areas they identify as specific needs or interests. The list of these tools in the network psychiatrist toolkit currently being developed for this purpose will include: Motivational Interviewing in a Primary Care Setting. Use of PHQ-2/9 as screening tools to identify and monitor progress in treatment of depression and anxiety. Use of SBIRT for early identification, brief intervention, and referral for substance abuse treatment as necessary in the Primary Care setting; use of the CRAFFT in the adolescent population for substance use identification. Use of generic medications in treatment of behavioral health conditions. Support of co-location models of care and reverse co-location models (bi-directional care). Each network psychiatrist and/or behavioral health coordinator will be trained to provide the above tools to PCPs through “lunch-and-learn” programs in individual primary care practices. These training efforts can be followed on an ongoing basis through audits and claims records to determine if these tools are being incorporated into daily practice. The identification of early PCP adopters of this training program and asking the practices to identify which of the tools it chooses to incorporate into practice will likely increase the adoption of the tools. Specific Behavioral Health Initiatives Chronic Pain Initiative Many primary care physicians have identified the management of chronic pain as a significant problem in their practice. In reality, it is an enormous problem that should be addressed in a community-wide system of care effort. Adequately addressing chronic pain management requires involvement by primary care, emergency departments, dental clinics, pain clinics, substance treatment programs, law enforcement and other community agencies. This approach was tested successfully in a four-year pilot project in a rural North Carolina county and will be used as a model across the Community Care networks. The outcomes of the pilot resulted in a decreased number of deaths by unintentional poisonings, decreased emergency department utilization, and higher provider and consumer satisfaction ratings. Through the network behavioral health teams and network management, Community Care will identify the early adopters of this Chronic Pain Initiative and support the system of care approach to chronic pain management. A+KIDS Registry In the A+KIDS Registry, the North Carolina Medicaid program and Community Care of North Carolina partnered with child psychiatry experts from the state’s four medical schools to develop a children’s registry program. It is a safety-monitoring program designed to ensure that any child enrolled in Medicaid who is prescribed antipsychotic medications for an "off-label" indication is monitored according to generally accepted guidelines. The program’s initial phase will include children ages 12 and under. Objectives of the A+KIDS registry include: improving the use of evidence-based safety monitoring for patients for whom an antipsychotic agent is prescribed; reduction of antipsychotic poly-pharmacy; and reduction of cases in which the FDA maximum dose is exceeded. This program has included all prescribers of antipsychotics in the identified population, including primary care and behavior health care physicians and extenders. Points to Remember for Behavioral Health Integration We can no longer support a silo system of care that ignores the reality that patients frequently possess mental and physical co-morbidity factors. The goals of supporting integrated care in North Carolina are to focus on early identification through screening, provision of brief intervention programs with treatment when appropriate, and support for referral to treatment when a significant behavioral health condition is identified. It is not necessary to “progress” along a continuum to achieve integration; it is possible to initiate any one of these models based on local resources and practice patterns. The main goal of this initiative was to develop collaborative relationships at the local level that would begin the process of coordination of care between the two systems with the hope of increasing integration of services as local relationships developed. The BH coordinators form the backbone of the Community Care BHI program and serve as a driving force in the integration efforts. The goal of the integrated care program is to provide PCPs with tools to better identify and treat, to their level of comfort, behavioral health conditions. When the condition exceeds the brief treatment models of primary care, the PCP should be able to recognize the need to refer to an appropriate behavioral health resource within the specialty behavioral health system.