JournalRockDecay_CaseHardenExample

advertisement

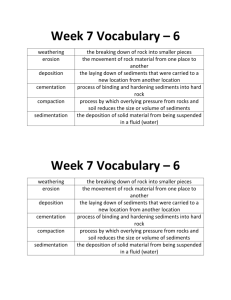

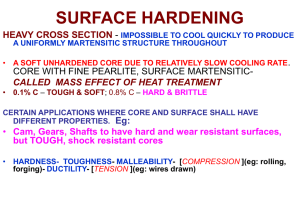

1 An Analysis of Case Hardening Phaedra Culley Geography Department Mesa Community College – Red Mountain Campus Mesa, AZ, 85207 and then Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning School Arizona State University Tempe AZ 85287-5302 1. Introduction to RASI Element: Case Hardening Case hardening occurs when an outer crust or shell forms on the very surface of a rock surface. This protection comes from the addition of hardening agents such as silica and iron to the outer few millimeters of a rock. Figure 1 shows and example of case hardening. Figure 1. This basalt boulder from has an ancient Hawaiian petroglyph carved into a surface protected by case hardening. In this example, silica glaze has moved into the weathering rind and indurated (hardened) the outer shell. The sunglasses provide a sense of scale. This image was taken by R. Dorn and was downloaded from Cerveny et al. (2007). 2 2. Brief Literature Review of Case Hardening Case hardening is formed by two processes: softening of the inner rock (or core) and hardening of the outer layer. Due to its sedimentary nature, sandstone tends to harden on the outside because of how the grains are held together. When a rock varnish begins to form, much of it can dissolve, and the amalgam of minerals and chemicals re-deposit into the pore spaces (or holes) in outer layer of the sandstone. These agents then begin to harden the exterior of the rock (Boxerman, 2012) (Figure 2). At this point, the rock begins to form the hardened outer shell, and this cycle continues until the stone has a protective coating (Dorn, 2004). Figure 2. Case hardening is associated with a weathering form called tafoni, or holes decayed out of rocks. Tafoni often starts out as alveoli, or smaller holes, that are sometimes seen on petroglyph panels. This is not an image of a petroglyph, but comes from the Lyons Sandstone at Red Rock Canyon, Colorado. Source: Photograph by Brandon Vogt in Boxerman (2012). Other types of rock such as granite tend to soften from the inside out (Dorn, 2004). The problem with case hardening is it leaves the area beneath it vulnerable to decay; therefore, the rock erodes differentially, and the core stone beneath decomposes at a faster pace than the outer crust. This often results in loss of the surface material from the original rock. This is a particular problem for petroglyphs, because at this point, they can scale off and become separated from the rock itself, resulting in loss of the panel, or a portion of it. 3 Case hardening can also refer to the deliberate hardening of steel by altering metal and forming a thin layer of alloy (Fitzgerald, 2006). In addition to areas like the carvings at the Petrified Forest, Arizona and other western states, case hardening examples have been cited in the carvings at places such as Petra, Jordan, and even some rocks on Mars. “Pot of Gold” and “Bread Box” are examples where the process occurred along joints in volcanic rock and formed similarly to stone previously described in this paper. Case hardening probably exists on Mars: “The case-hardened portions of these rocks have since been etched into relief by the wind, with the interiors having been largely removed by wind erosion. The major factor controlling this style of weathering was liquid water.” (Farmer, 2005) Case hardening creates a protective shell for whatever surface it forms on. 3. Visual Case Study of Case Hardening at Petrified Forest National Park The GIS of RASI forms at Petrified Forest National Park (Gutbrod, Cerveny, Dorn, Allen, & Gibson, 2012) provides an opportunity to study the nature of case hardening up close. By downloading and then zooming into different locations, I hypothesize that case hardening is associated with rock art preservation (Figure 3). It appears that the surfaces of sandstone rock faces are undergoing erosion. This destroys the rock art, and the last places where the rock art appears to be preserved are case hardening. Figure 3: Case hardening preserves rock art. The sandstone at Petrified Forest National Park appears to undergo spalling regularly. Spalling is the loss of the surface by detachment of pieces of different sizes. The case hardened areas, however, appear to be the last locations to spall. Thus, case hardening preserves 4 rock art more than the regular sandstone surface. Source of image: Gutbrod, Cerveny, Dorn, Allen & Gibson (2012). On the other hand, case hardening also appears to be associated with detachment of rock art. The rock directly underneath the case hardened shell appears to be the weak point. It has decayed so much that the petroglyph and its case hardening shell can no longer remain attached to the rock (Figure 4). Figure 4: This image shows the loss of rock art due to detachment of case hardening This panel from Petrified Forest National Park has formed a hard outer shell, known as case hardening. Due to the decay of the rock beneath (forming a weathering rind), portions of the panel have fallen off, resulting in the loss of part of the petroglyph. Source of image: Gutbrod, Cerveny, Dorn, Allen & Gibson (2012). 4. Spatial Analysis of Case Hardening at Petrified Forest National Park For my spatial analysis, I selected a cluster of rock art panels on the easternmost area that was analyzed at Petrified Forest National Park. The inset map in Figure 5. I selected this area because I do not understand the distribution of case hardened panels. Almost all of the panels in this area are scored as not having case hardening, except for a few. Given the dramatic pictures on how case hardening can impact sandstone rock surfaces (e.g. Figures 2-4), I expected to see a lot more case hardening scored at Petrified Forest National Park. The general absence of case hardening is thus perplexing to me. The next step in figuring out why this weathering form is so infrequent would be to visit this national park in person. The next best thing is to go to http://images.google.com/ 5 and search for petroglyphs Petrified Forest National Park. Many of the searched images do appear to have case hardening. Thus, the mystery depends for me as to why so many of these panels are scored as case hardening not present. Figure 5. Map of case hardening of an area at Petrified Forest National Park. I first zoomed in to the cluster of panels to screenshot the data. Then, I zoomed out to make the inset map. Both screen captures were turned into .jpg file, and I combined them using the website http://pixlr.com/ Source of image: Gutbrod, Cerveny, Dorn, Allen & Gibson (2012). 5. Comparable Feature in My Local Built Environment Now that I am aware of case hardening, I tend to see it in many different settings. Case hardening can help old buildings and structures such as the carvings in the cliff faces at Petra in Jordan, giving them the ability to resist wind or water abrasion. In the case of wood, paint protects fencing from weathering agents, and in metal, allows the surface to harden, while maintaining the integrity of the inside portion. On many homes, we use a Stucco layer to protect the walls, and stain or lacquer to protect furniture. I also think of case hardening when I see a callus, because the thickened skin is hardened; of course, the processes 6 producing these similar forms are very different. However, I also see case hardening around my college campus at Arizona State University (Figure 6), where different boulders used in landscaping show case hardening. Figure 6. Case hardening seen on sandstone sculpture at the Arizona State University Law Library. The raw material appears to be sandstone. The location of the watch shows ripples from when the sandstone was sand flowing in a stream. The ripples are hardened by what looks to be a light reddish agent, that could be silica glaze. Source: Phaedra Culley. 6. Conclusion: Importance of Case Hardening to Rock Art Conservation Case hardening’s importance to rock art conservation rests in its ability to preserve petroglyphs. The hardened outer shell of a rock art panel seems to allow the rock art to last longer. This is a very good thing in terms of helping to protect the art. At the same time, the images of fragments of panels (e.g. Figures 3 and 4) should be a warning sign that the remaining bit of art could break off at any time. The weakness of the weathering rind under the case hardened shell is the ‘weak link in the chain’. When site managers are made aware of panels that appear to be ‘hanging by a thread’, every effort should be made to preserve the art in other ways, such as extensive photography. The next time someone visits, the art could be gone. 7 7. Acknowledgments I owe Niccole Cerveny a great debt. Her gift of caring involved spending a lot of taking me and other students to Petrified Forest National Park, where my life was changed by conducting research. I encourage all students reading this article to get involved in an undergraduate research project, whether you are in a community college or a four-year institution. I would also like to acknowledge the producers of Battlestar Galatica for giving me something to listen to while researching case hardening. 8. References Cited Boxerman, J. (2012). Tafoni. Retrieved from http://tafoni.com/ Cerveny, N., Dorn, R. I., Gordon, S. J., & Whitley, D. S. (2007, October 24). Atlas of petroglyph weathering forms used in the rock art stability index (RASI). Retrieved from http://alliance.la.asu.edu/rockart/stabilityindex/RASIAtlas.html Dorn, R. I. (2004). Case Hardening. In A. Goudie, Encyclopedia of Geomorphology (pp. 118-119). London: Taylor & Francis Group. Farmer, J. D. (2005). Case-hardening of rocks on Mars: evidence for watermediated weathering processes. Retrieved from 2005 Salt Lake City Annual Meeting (October 16–19, 2005): http://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2005AM/finalprogram/abstract_96845.htm Fitzgerald, C. (2006, March). Case Hardening in a Home Garage. Retrieved from www.hemmings.com: http://www.hemmings.com/hsx/stories/2006/03/01/hmn_feature20.html Gutbrod, E., Cerveny, N., Dorn, R., Allen, C., & Gibson, S. (2012). Petrified Forest National Park GIS of petroglyph weathering forms used in the rock art stability index (RASI). Retrieved from http://hosted.seservices.us/elyssa/test_v1.html 9. Suggested Glossary Entry Case Hardening — Hardening the outer millimeter of an exposed rock surface by infilling of pores (tiny holes) in the rock with strengthening agents such as silica, iron, and manganese.