In Sir Henry Neville, Alias William Shakespeare, Mark Bradbeer and

advertisement

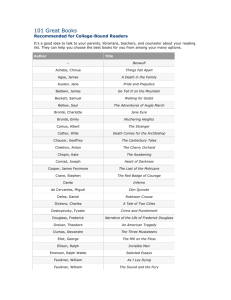

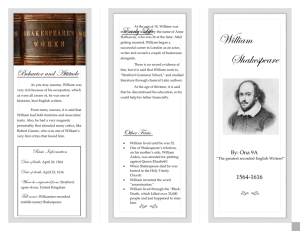

Book Review: by Professor R. John Leigh Sir Henry Neville, Alias William Shakespeare: Authorship Evidence in the History Plays 2015, published by McFarland & Company Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina In Sir Henry Neville, Alias William Shakespeare, Mark Bradbeer and John Casson provide further evidence to corroborate the hypothesis – first developed by Brenda James and William Rubinstein in their 2005 book “The Truth Will Out” – that Henry Neville was the real writer of the works attributed to Shakespeare. This book is a well researched, scholarly contribution, but is also an engaging read, packed with new information that will fascinate anyone with an open mind who is interested in the Shakespeare authorship debate. Drawing on the historical record and sources that were available to Henry Neville, Bradbeer and Casson build a case that the writer of the history plays deliberately distorted both the selection of individuals appearing in the plays and aspects of the historical narrative in such a way to place the Neville family in a favorable light. They also point out how Shakespeare’s history plays were political statements aimed at alerting the audience to contemporary events. Thus, spymaster Francis Walsingham (who knew both Neville and Christopher Marlowe) formed his own acting company probably to promote a view of history consistent with the notion that Elizabeth was the rightful monarch, something disputed, for example, by followers of Mary Queen of Scots. It follows that comparing the selection of the dramatis personae with the individuals who are historically recorded as playing significant roles, divergence of the plays’ plots from recorded history, and editorial changes in the play between successive quartos and the First Folio all provide clues to their authorship. The historical record documents how the descendants of Ralph Neville (1364-1425), first earl of Westmoreland, played prominent roles during reigns extending from King John to Henry VIII. Thus, one challenge for the authors is to show how the writer of each of the history plays deviated from this record – distinguishing their findings from what might be called a “false positive result” – consequent on the substantial number of Neville family members that populated this span of history. Their approach is to examine the plays in the order of the kings’ reigns rather than the order in which the plays are currently thought to have been written. They systematically identify characters present in the historical record that have been marginalized or promoted in the plays and use these findings to corroborate their hypothesis. For example, the bastard Falconbridge (historically the illegitimate son of William Neville) is a made the illegitimate son of Richard I and a hero in King John (Sir Henry Neville, himself, may have been born before his parents were legally married). In contrast, Ralph Neville (1456-1499), the third Earl of Westmoreland, who fought with Richard III at Bosworth Field and could therefore be seen in a negative light, is absent from the play. To buttress their carefully discussed historical evidence, Bradbeer and Casson also draw on probable sources used by Sir Henry Neville in writing the plays, including his handwritten copy of Leicester’s Commonwealth, Milles’ A Catalogue of Honor, and Holinshed’s Chronicles (which Neville’s father-in-law, Henry Killigrew had edited in 1587). In his prior book, Much Ado About Noting, Dr. Casson had pointed out the relevance of marginal notes made by Neville, especially in his copy of Leicester’s Commonwealth, to the plays attributed to Shakespeare. In addition, attention is given to the selection of words in the plays and their relevance to Sir Henry Neville; for example cannons anachronistically appear in King John and could be related to Neville’s taking over the Gresham ordnance business. Another line of evidence provided by the authors involves analyses of words used by Sir Henry Neville in his letters or speeches and their appearance in contemporaneous plays. For example, during the period when Henry V was thought to have been written, Neville was English ambassador to France, and wrote frequent letters to “Mr. Secretary Cecyll” in which he used rare words that Shakespeare used in that play. Bradbeer and Casson extend this approach in what is perhaps the most exciting chapter of the book, focusing on the statement made by Sir Henry Neville in his own defense at his trial in March 1601 for being involved in the failed Essex rebellion. The authors compare this statement with the text of Hamlet, identifying words common to both – individual, pairs, and phrases of three words, as well as rare words. They identify 426/1,379 words of the speech that are shared by the play, but acknowledge that this finding, as well as the occurrence of rare words, could just be coincidence. They then strengthen their case by conducting a “control experiment” in which they compare the text of Hamlet with words occurring in four letters by Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford (currently a popular alternative candidate for authorship of the plays), all written in 1601. Compared with Neville, De Vere’s letters showed about half as many words in common with Hamlet, and less words occurring together. The authors’ findings justify their call for further computer-aided analysis of the vocabulary of Neville to compare it with that of the Shakespeare canon. In sum, Sir Henry Neville, Alias William Shakespeare provides a wealth of new documentary evidence in support of this candidate. It is a fascinating book that will prompt further research and excite anyone interested in the Shakespeare authorship debate. R. John Leigh, M.D., F.R.C.P. Blair-Daroff Emeritus Professor of Neurology Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, Ohio, USA