Limestone Legacy - State Historical Society of Iowa

advertisement

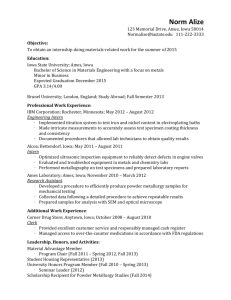

Limestone Legacy Iowa’s Amateur Paleontologist Three Iowans won international recognition for their lifelong study of Iowa's fossil crinoids. Because of their work, scientists around the world became aware of the remarkable fossils in the cliffs around Burlington and in the quarries near Le Grand and Gilmore City. Although Charles Wachsmuth, Frank Springer and Burnice H. Beane came from different backgrounds, they shared two things-- a lack of formal scientific training in geology, and a passionate quest for the study of ancient "flowers" of the Iowa seas, the crinoid. Charles Wachsmuth All his life illness plagued Charles Wachsmuth. It forced him to end his law studies in Germany and immigrate to Iowa in 1855. It inhibited his business aspirations as a grocer in Burlington. Yet poor health -- and his wife's help - was the catalyst for a new interest for Wachsmuth. As an amateur geologist, Wachsmuth would eventually earn international respect. Running a grocery store taxed Wachsmuth's health and slowly the management of the store shifted to Bernardina, his wife. Local doctors suggested he spend more time outdoors, and he began to wander the cliffs near his Burlington home. Wachsmuth eagerly began collecting and studying the crinoids he found. As his collection and knowledge grew, so did his reputation. In 1873 he has hired to study crinoids at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, by the Charles Wachsmuth (1829-1896) (1829-1896) famous geologist Louis Agassiz. As Wachsmuth's collections and knowledge increased he published his findings individually and with others authors. Bernardina enthusiastic support of her husband's work extended into the field collecting, and actively participation in the research and writing of his later publications. Many contemporary sources recognized their shared efforts however, authorship was only credited to Charles. Frank Springer While studying law at the University of Iowa, Frank Springer attended a lecture by Louis Agassiz and became interested in Paleontology. He established a law office in Burlington and a friendship with the Wachsmuths. Together they shared a passion for collecting and studying crinoids and to co-authored many publications. Springer attained fame as a New Mexico legislator, lawyer for the Atchison,Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, Frank Springer . and as president of the Maxwell Land Grant Company, (1848-1927) controlling nearly tow million acres of land. His interest in crinoids brought him back to Burlington and collaboration with the Wachsmuths. Together, Wachsmuth and Springer wrote Revisions of Paleocrinoidea, an attempt to order all known fossil crinoids. The 4 volume work recognized similarity and diversity within the crinoids. In itself the publication was to encourage more research and Springer and the Wachsmuths labored on Crinoidea Camerata of North America for seven years. Before its completion Charles Wachsmuth died and Bernadina completed the manuscript with Springer. The finished work consisted of 800 pages and 1500 illustrations. Bernice H. Beane In 1874 a small "nest" of crinoid fossils was uncovered in the Le Grand Quarry. They were so well preserved that scientists from Iowa, Illinois, New Mexico, Indiana, and Massachusetts visited the site and with the cooperation of the quarry owner they excavated the fossils over a sixteen year period. Charles Wachsmuth and Frank Springer were two of the scientists that visited the site They patiently answered the questions of young farm boy, --Burnice H. Beane and inspired him with their enthusiasm. Burnice Hartley Beane grew up on a farm at the edge of the Le Grand quarry. In the quiet times, between chores and schoolwork, he found time for his hobby -collecting insects, bird eggs, rocks, and finally fossils. Beane helped his mother manage the family farm while his father toured the Midwest as an evangelist Quaker minister. They sold their cash crops of strawberries, watermelon and potatoes in Marshalltown and other nearby towns. Burnice H. Beane (1879-1966) Beane to attended Penn College in Oskaloosa for a short time and then returned to the family farm near the edge of the quarry. Here he raised his family and continued his interest in the fossils of Le Grand. B. H. Beane and one of his four sons stand beside a wagon lift designed by his father. ca. 1910 Crushed stone for road and railway ballast, agricultural lime and building stone for the Old Iowa State Historical Building originated from the quarry. The quarry's most significant product however, is the small flower-like animals, crinoids, that are preserved in the rock. Le Grand Quarry Circa 1910 In 1909 the ownership of the Le Grand quarry passed to the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad. Stone Crusher The worlds largest rock crusher awaits the limestone from the Le Grand Quarry Company near the Beane farm. ca. 1900 Still interested in the crinoid he continued to maintained close ties with the quarry owner and workers.. Beane's most significant discovery came in 1931 when blasting exposed a cluster of ancient starfish. While workers loaded rock into the crusher, Beane chipped away at the block of stone to reduce it to a manageable weight. Still weighing over 600 pounds, he moved the slab to Beane's farm for study and careful cleaning . Beane, then 52, worked meticulously to uncover the delicate fossils. Upon preparation, the rock yielded the remains of 183 starfish, Schoenaster legrandensis, and a number of other specimens. This find and the care shown it its preparation gained Burnice Beane the interest of paleontologists and gained recognition in the scientific community across the world "The best discovery that I ever made was a slab of starfish . . . about five feet wide and about three feet thick, I think. And it took me two days to get it to work down from the wall so I could move it. When I got it so I could handle it at all, I used a plank to slide it onto a truck and took it home." Burnice Beane, 1958 Burnice Beane's painstaking skill in preparing the crinoids he saved from the crusher is a scientific legacy. Through his efforts many museums across the world share a portion of Iowa's past. The State Historical Society of Iowa is fortunate to exhibit many of the fossils preserved and prepared by Burnice H. Beane. Beane's interest in the Le Grand crinoid continued throughout his life, it filled his house with beautiful fossil slabs and benefited museums and universities around the world. As his fame spread, many paleontologists and amateur collectors sought his advice and an opportunity to tour the famous quarry with the man who had become the guardian of its treasures. WHAT IS A CRINOID? Crinoids are often called "sea lilies" or "feather stars". and are echinoderms (spinyskinned animals) with skeletal parts made of calcareous (limy) plates. They have radial symmetry, digestive, nervous, reproductive and water vascular systems. Their delicate arms strain tiny marine life from the sea and move it toward its mouth. inoid Some crinoids are stationary, while others move freely over the ocean floor or in floating mats. They may be found in all of the oceans of the world and at vastly different temperatures and depth The Crown includes the arms and the body, or calyx, of the animal. The Calyx is the plate-covered body. It contains the digestive systems and supports the arms, which help gather food. The plates of the calyx are arranged in a specific manner for each type of crinoid. Arms are the long appendages that reach out from the calyx. Pinnules are small extensions of the arms that help move water and food to the mouth. The Stem is made of individual disks with a central opening for nutrients and nerve impulses. Free living crinoids often lack stems. Columnal, or stem sections, is held together by flexible fibers which allowmovement. Shape and surfaces of the columnals may vary with each type of crinoid.Cirri are the "arms of the stem" that hold the crinoid to objects or the sea floor. The Hold Fast secures the crinoid to the sea floor much like tree roots. Free moving crinoids do not have hold fasts. This slab holds the remains of crinoids and other invertebrate that died on the Iowa sea floor 350 million years ago. At that time Iowa was located near the equator and submerged under a warm sea. The death of these animals was non-violent and their bodies drifted into this depression to gently settle onto the limy mud. Layers of lime covered their remains and preserved them from destruction. When excavated their bodies lie randomly across the stone and show no current or wave action. We do not know why these animals died. Did the water temperature rise? Did the salinity become change? Were they suffocated by water that was too muddy ? We may never know. The exhibit aquarium shows modern marine invertebrates who’s relatives lived in Iowa’s Mississippian period, 350 million years ago. Chambered Nautilus Sea Urchin (Spikes) Marine Worm Feather Star (crinoid) From modern crinoids we observe that: Crinoids eat plankton and live in areas where of plankton live. Crinoids grow many arms in warm water, few arms in cool water. Crinoids may be stationary or free moving. Crinoids may live in concentrations on the ocean floor or as floating mats. Crinoids are colorful. and Crinoids may regenerate lost parts. Example of Crinoids from Le Grande, Iowa Taxocrinus intermedius Dichocrinus inornatus Rhodocrinus kirbyi & Platycrinus symmetricus Crinoids of the Mississippian period. Kinderhook Series, Hampton Formation Le Grand, Iowa A Question of Ethics Fossils are rare glimpses of past life. Countless animals die each year but only a few are protected from decay, sheltered in the layers of earth, to become fossils. Even fewer are ever found. After lying undisturbed for millions of year, exposure at the surface endangers the fossil. Mining, construction, and erosion destroy countless fossils. Wind and water naturaly wear away delicate structures and scatter fragments. A fossil that is discovered by a caring individual and preserved for study is rare.