Full Text (Final Version , 279kb)

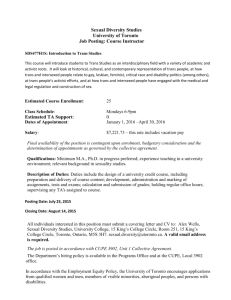

advertisement