`Developing theory in organisational research and practice in

advertisement

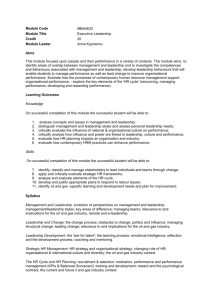

1 ‘Developing theory in organisational research and practice in educational settings’ A Research Seminar at the University of Bath Wednesday 13th and Thursday 14th June 2007 Managing Organisational Culture, Managing Change: Towards an Integrated Framework of Analysis Michael D. Wilson School of Education University of Leeds Introduction Framing the problem There is broad agreement among researchers that organisational culture is an important but a frequently overlooked component of school improvement. It has been described as holding the clue to a ‘missing link’ in school improvement research and in explaining the process of institutional change. Arguably it is of more fundamental importance than various instrumental reform initiatives linked to government policy, structural changes in the organisation of schools and the setting of numerous school performance targets (Wagner & Masden-Copas, 2002, p.42). Therefore, given the extensive background and history of research into organisational culture, it is perhaps surprising that it should be described a ‘missing link’ in understanding the process of organisational change and improvement. An explanation can be found partly in the concept of culture itself, which remains ontologically problematic. Berger (1995), for example, claims that anthropologists have advanced more than a hundred definitions of culture, while Prosser (1999) refers to school culture having a “profusion of meanings”. Terms such as organisational culture, climate and ethos have often been illdefined and loosely applied with the result that “such ad hoc meanings and assumptions have undermined critical reflection and impeded school culture research” (Prosser, 1999, p.5). Another possible explanation is that there has been a lack of alignment between cultural research and the leadership and management of organisational change. While cultural research has become increasingly complex and challenging, partly because of its interdisciplinary nature (Alusuutari, 1995), there has been a concern that many studies of organisational effectiveness and change management have tended to offer neat, prescriptive packages for improvement based on overly simplistic models of culture (Seel, 2005). The aims of the presentation This presentation has three aims, each underpinned by a key question for discussion. The first is to put forward the proposition that studies related to organisational culture can be categorised into two broad contrasting typologies: the functionalist and the dynamic-unbounded (based on Knight & Trowler, 2001, p.56). The two perspectives are described and their respective strengths and weaknesses highlighted. It is demonstrated that neither model can be regarded as entirely satisfactory in providing a comprehensive framework for an analysis of either the nature of 2 organisational culture or how school leaders effectively manage culture to bring about organisational change and improvement. The second aim is to suggest that the two typologies, although presenting contrasting views of organisational reality, are not necessarily incompatible or mutually exclusive – that when combined and integrated can foster a deeper, more comprehensive understanding of school culture and how it might be effectively managed. The third aim is to consider the implications for future research into school culture. Typologies of Culture Question 1: How useful as a conceptual tool are the functionalist and the dynamic-unbounded perspectives of organisational culture? The functionalist perspective Definitions of culture which reflect the underlying assumptions of the functionalist model emphasise culture as the ‘glue’ which binds an organisation together through a sense of interdependency, shared values, agreed norms and a common sense of purpose drawn from both shared wider societal values (Hofstede, 1991), values rooted in the history and tradition of the organisation itself (Hanson, 2003, pp.60-61; Schein, 1985, p.6; Deal & Kennedy, 1983, p.14), and values arising from a conflation of societal and organisational norms (Walker & Dimmock, 2002; Wilson, 2005). It emphasises unity and consensus, so that culture has both ‘reality-defining’ and ‘problem solving’ functions ‘inherited from the past’ (Hargreaves, 1995, p.25). As such, organisational culture is perceived as essentially holistic and homogeneous, pervading and influencing the entire organisation. The primacy of understanding organisational culture is as it currently is through a static or synchronic perspective. It has much in keeping with an autopoietic approach to organisational theory, emphasising an organisation’s capacity for self-production through a closed system of relations, in which the external environment is regarded essentially an extension of the organisation’s own sense of identity, interests and concerns (Morgan, 1997, pp.253-258; Seidl, 2005). The attraction of the model from the standpoint of institutional improvement is that leaders can audit their organisational cultures. They can be proactive in strengthening cherished norms and traditions, and in bringing about intentional change in the interests of maintaining or creating, through a process of reculturing or “normative re-education” (Stoll, 1999), a ‘strong’ culture conducive to continuous improvement and long-term institutional success (Reeves, 2006). Change is therefore viewed as predictable, rationally determined, and brought about as a result of strategic planning based on an initial audit or internal evaluation, thus following a logical step-bystep approach to effective change management (e.g. Kotter, 1996). The use of inventories for diagnosing school culture is therefore consistent with both the functionalist model of organisational culture and school effectiveness research. Maslowski (2006) provides a critical review of six such inventories, concluding that while they have limitations they serve a useful function in helping schools to identify cultural elements that need to be improved and in contributing to comparative studies across schools. The functionalist perspective of organisational culture has a number of limitations. First, its emphasis on quantitative methods suggests that what it actually measures has more in keeping with notions of school climate than school culture, where the former “can be defined as the pervasive quality of a school environment experienced by students and staff which affects their behaviour” (Hoy & Sabo, 1998; see also Maxwell & Thomas, 1991). Hoy & Sabo (1998) indeed express a preference for the term school climate, because of its emphasis on survey technology, 3 its utility as an independent variable in exploring student outcomes, and the ability of such measures to provide a snapshot of an organisation’s perceived strengths and weaknesses with the expressed purpose of managing change (see also Roach et al, 2004). However, arguably the narrowness of its scope limits a deeper understanding of culture that takes into account more subtle levels of meaning, taken-for-granted values and basic assumptions held by members of the organisation as described by Schein (1985, p.14). A second limitation is that a functionalist perspective underplays the impact of externally determined change processes, personal agency, structural contradictions, and the potentially dysfunctional impact of various organisational subcultures and associated micro-political processes, especially in large complex organisations, thus relying too heavily on what might be termed “consensus theory” (Holmwood, 1995). Although cultural unity and consensus are regarded as typical of ‘strong’ organisational cultures, the feasibility (or even desirability) of achieving such cultural homogeneity in diverse and/or multicultural organisations is open to question. In the words of Shields et al (2002, p.132) “a community of difference … begins, not with an assumption of shared norms, beliefs and values, but with a need for respect, dialogue and understanding.” There is a third limitation: although many of the inventories for diagnosing school culture have been validated statistically within certain parameters, there will be a need to review critically – and in all probability adapt – such instruments to meet the needs of schools in different cultural contexts, especially in non-Western societies. The dynamic-unbounded perspective In contrast to the functionalist perspective, a dynamic-unbounded typology emphasises the ever changing nature of organisational culture. From an external perspective, leadership challenges are expressed more in terms of the need to adapt and to manage flexibly as a means of coping with complexity, diversity, social inclusion, ambiguity and medium to long-term uncertainty (not to say turbulence) arising from externally driven change. Such change can be seen through the impact of globalisation, government reform and ongoing social changes associated with multiculturalism (in all its guises) and immigration – what in essence has been termed a process of ‘cultural flow’. The management of organisational change is therefore understood from an open systems perspective in the organisation’s reaction to external forces and its adaptation and responsiveness to external needs and demands. From an internal perspective, organisational culture is understood more in terms of heterogeneity and diversity: of organisations characterised by “loosely coupled systems” (Weick, 1976), a complex pattern of institutional subcultures and “multiple interactions” both between individuals and units (Prosser, 1999). How subcultures create tension, if not division, and serve to undermine consensus and shared norms and values (assumptions of the functionalist model), has become evident form the insights of the work of such researchers as Siskin (1997) and Becher & Trowler (2001) on the divisive effects of departmental subcultures, Thrupp (2001) on the differential impact of middle- and working-class subcultures on student attitudes to schooling, and Walker (2002) on the dilemmas facing Chinese headteachers in managing conflict and cultural diversity. A dynamic-unbounded perspective of culture relies on a qualitative research methodology rooted in case study (e.g. Wilson & Prosser, 2006) and techniques associated with a wide range of social disciplines and approaches to investigation, including social anthropology, visual ethnography, sociology, semiotics, proxemics (spatial relationships as indicators of cultural behaviour) and kinesics (posture, gesture and body language as signifiers of culture) (Prosser, 2007). As important as the spoken word undoubtedly is to interpretative research of this kind, there has been a growing emphasis on a deeper understanding of organisational culture through observational 4 techniques. Prosser (2007), for instance, discusses how three focal points of observation can deepen our understanding of school culture: school architecture (how buildings affect and determine relationships and teaching and learning environments); non-teaching space (including insights into staff subcultures from observing affiliations in staff rooms, and insights into pupil subcultures through the observation of territorial domains, contested space and bullying in playgrounds – the hidden curriculum); and teaching and learning (through the observation and analysis of classroom layout and human interaction through the use of video recording and photographic inventories). Although undoubtedly fruitful in creating profound and detailed insight into organisational culture, a dynamic-unbounded perspective with its reliance on the generation of rich qualitative data does not necessarily provide a template for measuring school effectiveness or for identifying priorities for change and improvement in school culture. As such, its immediate value to school effectiveness and school improvement in purely functional and pragmatic terms may be viewed by some as relatively limited. Towards Integration Question 2: How might the two models be integrated to provide a more comprehensive conceptual framework for understanding both school culture and its implications for effective school leadership? To assist in the process, the cross-tabulation of the two typologies (see Appendix) is aimed at highlighting the key features and contrasts between the two models. A key issue raised by this question is theoretical triangulation. In general terms, the desirability of triangulation is that the limitations of one perspective can be compensated by the strengths in the other. However, the two theoretical constructs could serve different purposes, in which case it would be legitimate to ask how far such integration is possible or even desirable. In assessing the implications for effective school leadership, the functionalist paradigm is consistent with traditional mainstream leadership theories, which are universalistic and normative in offering generic frameworks for an understanding of leadership and leadership effectiveness. Although many of the basic principles espoused in such theories have a universal significance to schools, including the need for strong leadership with high expectations, shared values, quality assurance and an emphasis on teaching and learning, specifically how to achieve such aspirations within a complex, diverse and frequently changing organisational context is an issue that has been inadequately addressed in mainstream theory. Traditional leadership theories were not conceived to address issues of diversity and uncertainty; rather they originated as predominantly task and output oriented models formulated to manage a largely homogeneous workforce before globalisation and intercultural competence entered into the discourse of leadership and management. DiTomaso et al (1996, p.181) further suggest that there is a need to examine the assumptions underlying current models of leadership on the grounds that they pay insufficient attention to dealing with the emotions, organisational structures and processes whereby visions are transformed into reality. From a dynamic-unbounded perspective of school culture, leadership requires additional qualities, including the ability to manage externally imposed change which can be both uncertain and unpredictable. It also requires the ability to manage an ever increasingly diverse and multicultural community, where shared values and unity of purpose cannot be taken for granted. Given the complexity and difficulty of such leadership challenges, there is a powerful argument 5 to suggest that effective leadership from a dynamic-unbounded perspective requires an “intercultural communicative competence” that transcends conventional leadership models (Dreachslin et al, 2000, p.1412). Although not specifically focused on the educational sector, Chen & Van Velsor (1996) provide a useful composite model for diversity competency and leadership effectiveness, suggesting the need for the development of three key types of interrelated leadership skills: Motivational: a value orientation towards others and a willingness to work towards building harmonious relationships. Cognitive: the acquisition of knowledge and an understanding of the cultural values and norms of diverse groups. Behavioural: the skills of working with others who have diverse backgrounds. In short, from a dynamic-unbounded cultural perspective effective leaders will need to be flexible and, above all, be “people developers”, both at the individual and the group level, helping subordinates to work more effectively with diverse others (Chen & Van Velsor, 1996: 299). Such a perspective has major implications not only for the way we perceive leadership for schools in diverse and rapidly changing contexts, but also for ways in which we train and support our future school leaders. Implications for Research Methodology Question 3: How might research promote greater understanding of both the nature and the impact of organisational culture? Alusuutari (1995) suggests how future cultural research can draw on a number of approaches based on three main research traditions. Although addressing a general audience, his detailed exploration of the associated methodologies and the relationships between them has significance to the future direction of the study of school cultures: Qualitative studies based on anthropology and sociology, including ethnographic observation, symbolic interactionism and interviewing (both personal and group). Language studies, including semiotics, narrative analysis, discourse analysis and conversational analysis. Quantitative analysis through tabulations and establishing statistical relations so that relationships and patterns between variables become more clearly evident, thus providing useful clues and aiding the search for new questions. Two recent studies can be used to illustrate the potential of both quantitative and qualitative methodologies in assessing the role of culture in school effectiveness and school improvement. The first study by Wagner & Masden-Copas (2002) is an assessment of two North American initiatives in linking school culture to school improvement. The first initiative, the School Culture Triage Survey, is an inventory which has been used to profile school cultures both in the USA and Canada. Although not included in the Malinowski (2006) evaluation study, research has indicated a high positive correlation between variables of so-called ‘healthy’ school cultures used in the instrument and high student assessment scores. It therefore illustrates the diagnostic value of applying quantitative techniques to an analysis of school culture. The second initiative evaluated by the authors is the School Culture Audit, a school culture assessment used extensively in American public schools across North Carolina, Florida and Kentucky. As a tool it 6 succeeds in integrating both quantitative and qualitative methodologies in its five steps to facilitating school improvement. It therefore combines both breadth of perception (through a questionnaire survey) with depth of understanding through interviews, observation and evaluation. It is not restricted to a snapshot of school culture as the audit can be repeated at intervals to assess progress. The approach also has much in keeping with the tenets of appreciative enquiry. Rather than asking, “What is wrong with this place?” the audit asks, “What in your opinion would make this school the best it can be?” Or, as Cooperrider & Srivastva (1987) would say: the “miracle to be embraced” rather than the “problem to be solved”. The five steps involve: Interviews Observations Survey Evaluation Presentation The second study by Angelides & Ainscow (2000) applies the critical incident technique (Tripp, 1993) to an understanding of school culture and how this might lead the way to school improvement. This is essentially a qualitative research process, based on the observation of socalled critical incidents, followed by discussion and reflection through interviews with a variety of stakeholders to explore ‘multiple realities’. Through generating understanding of critical incidents in school life which is both shared and profound, it is in turn possible to understand the school’s culture and its contribution to organisational improvement, whether in real or potential terms. In order to help frame the discussion, potential future research questions might be considered within four main categories: Why questions related to the purpose of the research, including the functionalist perspective on issues of self-directed organisational improvement, or in contrast issues more strongly emphasised in the dynamic-unbounded paradigm including those specifically related to the management of the interface between organisational culture and the external environment. What questions related to the focus of the research, e.g. customs and conventions; history and traditions; values and belief systems; rituals and symbols; language and discourse; communications and networks; space and time utilisation; international and intercultural comparisons. How questions related to (a) issues of methodology, e.g. exploring the potential of a variety of methods, including documentary analysis, cultural audits, interviews and visual ethnography; (b) issues of leadership and management, e.g. how the visual culture of organisations is managed, how it impacts on teaching and learning, how schools evaluate and change their cultures. Who questions related to who should be involved and who should determine and control the research agenda, raising ethical issues of agency and control, e.g. in the case of schools conducting cultural audits for self-evaluation and improvement on the lines of action/practitioner research, or in the case of university researchers conducting academic research with the co-operation of case study organisations. 7 References Alusuutari, P. (1995) Researching Culture: Qualitative Method and Cultural Studies. London: Sage. Angelides, P. & Ainscow, M. (2000) ‘Making Sense of the Role of Culture in School Improvement’, School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 11 (2), pp.145-163. Becher, T. & Trowler, P. (2001) Academic Tribes and Territories: Intellectual Enquiry and the Culture of Disciplines. Buckingham: SRHE & Open University press. Berger, A. (1995) Cultural Criticism. London: Routledge. Chen, C.C. & Van Velsor, E. (1996) ‘New Directions for Research and Practice in Diversity Leadership’, The Leadership Quarterly, 7 (2), pp.285-302. Cooperrider, D.L. & Srivastva, S. (1987) ‘Appreciative Inquiry in Organizational Life’, Research in Organizational Change and Development, vol.1, pp.129-169. Deal, T. & Kennedy, A. (1983) ‘Culture and School Performance, Educational Leadership, 40 (5), pp.14-15. Dimmock, C. & Walker, A. (2005) Educational Leadership: Culture and Diversity. London: Sage. DiTomaso, N. & Hooijberg, R. (1996) ‘Diversity and the Demands of Leadership’, The Leadership Quarterly, 7 (2) 163-187. Dreachslin, J.L., Hunt, P.L. & Sprainer, E. (2000) ‘Workforce diversity: implications for the effectiveness of health care delivery teams’, Social Science and Medicine, 50, 1403-1414. Hanson, E.M. (2003) Educational Administration and Organizational Behavior. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Hargreaves, D. (1995) ‘School culture, school effectiveness and school improvement, School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 6, pp.23-46. Hargreaves, D. (1999) ‘Helping practitioners explore their school’s culture’, in Prosser, J. (ed.) (1999) School Culture. London: Paul Chapman. Hofstede, G. (1991) Cultures and Organizations: Software of the mind, London: McGraw-Hill. Holmwood, J. (2005) ‘Functionalism and its Critics’, in Harrington, A. (ed.) Modern Social Theory: An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.87-109. Hoy, W.K. & Sabo, D.J. (1998) Quality Middle Schools: Open and Healthy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Knight, P.T. & Trowler, P.R. (2001) Departmental Leadership in Higher Education. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press. Kotter, J.P. (1996) Leading Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Maslowski, R. (2006) ‘A review of inventories for diagnosing school culture’, Journal of Educational Administration, 44 (1), pp.6-35. Maxwell, T.W. & Thomas, A.R. (1991) ‘School climate and school culture’, Journal of Educational Administration, 29 (2), pp.72-82. Morgan, G. (1997) Images of Organization, London: Sage. Prosser, J. (ed.) (1999) School Culture. London: Paul Chapman. Prosser, J. (2006) ‘Changing culture: improving curriculum leadership’, Curriculum Management Update, 62, pp.3-6. Prosser, J. (2007) ‘Visual methods and the visual culture of schools’, Visual Studies, 22 (1), pp.13-30. Reeves, D. (2006) ‘How Do You Change School Culture?’ Educational Leadership, 64 (4), pp.92-94. Roach, A.T. & Kratochwill, T.R. (2004) ‘Evaluating School Climate and School Culture’, Teaching Exceptional Children, 37 (1), pp.10-17. 8 Schein, E.H. (1985) Organizational Culture and Leadership: A Dynamic View. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Seel, R. (2005) http://www.new-paradigm.co.uk [accessed on 16th March 2007]. Seidl, D. (2005) Organisational Identity and Self-Transformation: An Autopoietic Perspective. Williston, VT: Ashgate Publishing. Shields, C.M., Laroque, L. & Oberg, S.L. (2002) ‘A Dialogue about Race and Ethnicity in Education: Struggling to Understand Issues in Cross-Cultural Leadership’, Journal of School Leadership, 12 (2), pp.116-137. Siskin, L. (1997) ‘The challenge of leadership in comprehensive high schools: school vision and department divisions’, Educational Administration Quarterly, 33, pp.604-623. Stoll, L. (1999) ‘School Culture: Black Hole or Fertile Garden for School Improvement?’, in Prosser, J. (ed.) School Culture, London: Paul Chapman. Thrupp, M. (2001) ‘Sociological and political concerns about school effectiveness research: time for a new research agenda?’ School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 12 (1), pp.7-40. Tripp, D. (1993) Critical Incidents in Teaching. London: Routledge. Wagner, C. & Masden-Copas, P. (2002) ‘An audit of the culture starts with two handy tools’, Journal of Staff Development, 23 (3), pp.42-53. Walker, A. & Dimmock, C. (2002) ‘Cross-Cultural and Comparative Insights into Educational Administration and Leadership’, in Walker, A. & Dimmock, C. (eds.) School Leadership and Administration: Adopting a Cultural Perspective, London: RoutledgeFalmer. Walker, A. (2002) ‘Hong Kong Principals’ Dilemmas’, in Walker, A. & Dimmock, C. (eds.) School Leadership and Administration: Adopting a Cultural Perspective. London: RoutledgeFalmer. Weick, K. (1976) ‘Educational organizations as loosely-coupled systems’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, pp.1-19. Wilson, M. & Prosser, J. (2006) ‘Case Study: Transforming the culture of Prince Henry’s Grammar School Specialist Language College’, Curriculum Management Update, 62, pp.710. Wilson, M. (2005) ‘Leadership and organizational culture’, in Dimmock, C. & Walker, A. Educational Leadership: Culture and Diversity, chapter 4. London: Sage. 9 APPENDIX Cross-Tabulation of the Functionalist and Dynamic-Unbounded Models of Organisational Culture as Ideal Types Elements Functionalist Perspective Dynamic-Unbounded Perspective Culture is holistic, homogeneous, stable and binds the organisation Culture is heterogeneous, loosely coupled and diverse (subcultures) Change is intentional, internally planned and predictable Change is externally driven, ambiguous and uncertain Change strategies are proactive Change strategies are reactive and flexible An internal process model An open systems model Rational planning Ambiguity models & flexible planning Quantitative survey Qualitative case study Measuring school ‘climate’ Illuminating school ‘culture’ Critical and prescriptive Interpretative Purpose Heuristic device for reculturing the organisation Depth of understanding Leadership Implications Maintaining strong cultures Managing diversity Driving change for effectiveness and improvement Managing ambiguity and uncertainty Understates the role of subcultures, diversity, internal conflict and external constraints on internal cultural change capabilities Offers no ready blueprint for school effectiveness and/or school improvement. Assumptions Perspectives Methodology Limitations Audits can be of questionable validity in assessing school culture.