Who were the Mamluks? World History Name: E. Napp Date

advertisement

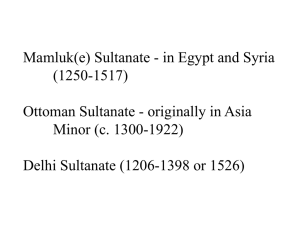

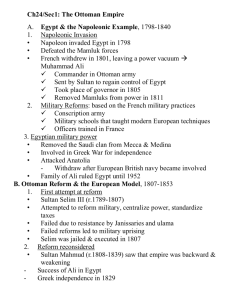

Who were the Mamluks? World History E. Napp Name: __________________ Date: __________________ Historical Context: “A Mamlūk, also spelled Mameluke, [was a] slave soldier, a member of one of the armies of slaves that won political control of several Muslim states during the Middle Ages… The use of Mamlūks as a major component of Muslim armies became a distinct feature of Islamic civilization as early as the 9th century C.E. The practice was begun in Baghdad by the ʿAbbāsid caliph al-Muʿtaṣim (833–842), and it soon spread throughout the Muslim world. Moreover, the political result was almost invariably the same: the slaves exploited the military power vested in them to seize control over the legitimate political authorities, often only briefly but sometimes for astonishingly long periods of time. Thus, soon after al-Muʿtaṣim’s reign the caliphate itself fell victim to the Turkish Mamlūk generals, who were able to depose or murder caliphs almost with impunity. Although the caliphate was maintained as a symbol of legitimate authority, the actual power was wielded by the Mamlūk generals; and by the 13th century, Mamlūks had succeeded in establishing dynasties of their own, both in Egypt and in India, in which the sultans were necessarily men of slave origin or the heirs of such men. This process of usurping power was epitomized by and culminated in the establishment of the Mamlūk dynasty, which ruled Egypt and Syria from 1250 to 1517 and whose descendants survived in Egypt as an important political force during the Ottoman occupation (1517–1798). The Kurdish general Saladin, who gained control of Egypt in 1169, followed what by then constituted a tradition in Muslim military practice by including a slave corps in his army in addition to Kurdish, Arab, Turkmen, and other free elements. This practice was also followed by his successors. Al-Malik aṣ-Ṣāliḥ Ayyūb (1240–49) is reputed to have been the largest purchaser of slaves, chiefly Turkish, as a means of protecting his sultanate both from Ayyūbid rivals and from the crusaders. Upon his death in 1249 a struggle for his throne ensued, in the course of which the Mamlūk generals murdered his heir and eventually succeeded in establishing one of their own number as sultan. Thenceforth, for more than 250 years, Egypt and Syria were ruled by Mamlūks or sons of Mamlūks.” ~ Britannica What are the main points of the passage? 1234567- The Article: Goodbye to the Mamluks; Economist Magazine, December 23, 1999 IN AUGUST 1516, on the plain of Marj Dabik in northern Syria, an Ottoman army smashed the forces of the Mamluk sultan of Cairo. The Turkish victory abruptly ended Cairo’s 500-year domination of the central lands of Islam. For 400 years, half the Mediterranean and most of the Arab world would henceforth be ruled from Constantinople. The event stunned contemporaries. Since taking power in Cairo in the 13th century, the Mamluks – a samurai-like regime of mercenary slaves turned masters – had been the mightiest force in the Middle East. It was they who chased the crusaders out of Palestine, they whose superb cavalry fought off Genghis Khan and his Mongol army in 1260. A later Mongol onslaught, led by Tamerlane, who seized Damascus and then, in 1401, sacked Baghdad, had left Cairo the greatest city in Islam. The Mamluk Empire stretched from Alexandria to Aleppo, and far to the south-east beyond Mecca. It monopolized the global spice trade, driving Portuguese venturers around the Cape of Good Hope, and Spanish fleets to the Americas, in search of alternative sources. The shock was not just that this mighty empire had been beaten. The scale of its defeat was appalling. The 75-year-old Mamluk sultan, Qansuh al-Ghuri, had marched to Syria in style. His magnificent train included 50 camel-loads of gold, and 40 huge illuminated Korans. Besides the chiefs of all Cairo’s courts and guilds and dervish orders, he had brought along the caliph, Mutawakkil, latest of the Abbasid family, whose lineage as titular leader of Islam extended back 800 years. For the past 250 of them, Mamluk sultans had used these powerless caliphs as props to legitimize their own rule. The battle was over in 20 minutes. As it began, the commander of the Mamluk left flank pulled his troops out. This treachery (it earned him an Ottoman governorship) assured the rout of the Mamluks. The sultan was killed, the caliph shipped to Constantinople as a prisoner. The Abbasid line had ended, and Ottoman rulers would now claim its perquisites. The Ottoman sultan, Selim the Grim, on entering Aleppo insultingly dispatched a lame clerk leaning on a cane to take the citadel, where al-Ghuri had parked his camel-loads of treasure. Within a year the rest of the Mamluk realm had fallen. Within 20 the Ottoman Turks ruled almost all the Arab world, except for distant Morocco and Oman. One battle had transformed an essentially European power into a great IslamicMediterranean empire. Selim's successor, Suleiman the Magnificent, was now the richest potentate on earth, Servant of the Holy Places and Commander of the Faithful. With 480 years of hindsight, the fall of the Mamluks looks less surprising than at the time. The forces at Marj Dabik were not balanced. The 20,000 Mamluks relied on tactics and equipment perfected in the 13th century. The highly trained, horsemounted archers at the core of their army were no match for Ottoman foot-soldiers wielding new-fangled arquebuses, nor for the Turks' deadly light artillery. The Ottomans' logistics, with separate corps for transport, engineering, food supply and surgery, enabled them to keep 60,000 men in the field. The Ottomans also represented a new kind of thinking. The regimes they replaced were feudal and venal. In the Mamluk realm, non-Muslims had been tolerated, but only just. The Ottomans had a different vision. Like the British in 19th-century India, they respected local grandees. They also installed a cohesive system of taxes and administration. Customs tariffs were kept low, and foreign merchants welcomed. Enjoying nearly autonomous status, the empire’s large religious minorities prospered. For all its later decay, in its early centuries the Ottoman Empire was an outstanding success. Yet the very success of its system sowed the seeds of future trouble. As a loose collection of sanjaks, beyliks, bishoprics and rabbinates, tied to Constantinople with the flimsiest of threads, the peoples of regions like the Balkans and the Middle East got along fairly well. But schisms would eventually arise. Ethnic and religious nationalism, those gloomy fashions of the 20th century, were to make the Ottoman mix explosive.” What are the main points of the passage? 12345678910The Art of the Mamluk Period: (1250 – 1517) ~ Suzan Yalman; Department of Education, The Metropolitan Museum of Art “The Mamluk sultanate (1250 – 1517) emerged from the weakening of the Ayyubid realm in Egypt and Syria (1250–60). Ayyubid sultans depended on slave (Arabic: mamluk, literally ‘owned,’ or slave) soldiers for military organization, yet mamluks of Qipchaq Turkic origin eventually overthrew the last Ayyubid sultan in Egypt, alMalik al-Ashraf (r. 1249–50) and established their own rule. Their unusual political system did not rely entirely on family succession to the throne – slaves were also recruited into the governing class. Hence the name of the sultanate later given by historians. Following the defeat of Mongol armies at the Battle of cAyn Jalut (1260), the Mamluks inherited the last Ayyubid strongholds in the eastern Mediterranean. Within a short period of time, the Mamluks created the greatest Islamic empire of the later Middle Ages, which included control of the holy cities Mecca and Medina. The Mamluk capital, Cairo, became the economic, cultural, and artistic center of the Arab Islamic world. Mamluk history is divided into two periods based on different dynastic lines: the Bahri Mamluks (1250–1382) of Qipchaq Turkic origin from southern Russia, named after the location of their barracks on the Nile (al-bahr, literally ‘the sea,’ a name given to this great river), and the Burji Mamluks (1382–1517) of Caucasian Circassian origin, who were quartered in the citadel (al-burj, literally ‘the tower’). After receiving instruction in Arabic, the fundamentals of Islam, and the art of warfare, slaves in the royal barracks were manumitted and given responsibilities in the Mamluk hierarchy. The Bahri reign defined the art and architecture of the entire Mamluk period. Prosperity generated by the east-west trade in silks and spices supported the Mamluks’ generous patronage. Despite periods of internal struggle, there was tremendous artistic and architectural activity, developing techniques established by the Ayyubids and integrating influences from different parts of the Islamic world. Refugees from east and west contributed to the momentum. Mamluk decorative arts – especially enameled and gilded glass, inlaid metalwork, woodwork, and textiles – were prized around the Mediterranean as well as in Europe, where they had a profound impact on local production. The influence of Mamluk glassware on the Venetian glass industry is only one such example. The reign of Baybars’s ally and successor, Qala’un (r. 1280–90), initiated the patronage of public and pious foundations that included madrasas, mausolea, minarets, and hospitals. Such endowed complexes not only ensured the survival of the patron’s wealth but also perpetuated his name, both of which were endangered by legal problems relating to inheritance and confiscation of family fortunes. Besides Qala’un's complex, other important commissions by Bahri Mamluk sultans include those of al-Nasir Muhammad (1295–1304) as well as the immense and splendid complex of Hasan (begun 1356). These structures were emulated by highranking officials and influential emirs who built similar foundations, such as the complex of Salar and Sanjar al-Jawli (begun 1303) and that of the emir Shaykhu (1350–55). The Burji Mamluk sultans followed the artistic traditions established by their Bahri predecessors. Although the state was faced with its greatest external and internal threats in the early fifteenth century, including the devastation of the eastern Mediterranean provinces by the Central Asian conqueror Timur (Tamerlane; r. 1370–1405), as well as famine, plague, and civil strife in Egypt, patronage of art and architecture resumed. Mamluk textiles and carpets were prized in international trade. In architecture, endowed public and pious foundations continued to be favored. Major commissions in the early Burji period in Egypt included the complexes built by Barquq (r. 1382–99), Faraj (r. 1399–1412), Mu’ayyad Shaykh (r. 1412–21), and Barsbay (r. 1422–38). In the eastern Mediterranean provinces, the lucrative trade in textiles between Iran and Europe helped revive the economy. Also significant was the commercial activity of pilgrims en route to Mecca and Medina. Large warehouses, such as the Khan al-Qadi (1441), were erected to satisfy the surge in trade. Other public foundations in the region included the mosques of Aqbugha al-Utrush (Aleppo, 1399–1410) and Sabun (Damascus, 1464) as well as the Madrasa Jaqmaqiyya (Damascus, 1421). In the second half of the fifteenth century, the arts thrived under the patronage of Qa’itbay (r. 1468–96), the greatest of the later Mamluk sultans. During his reign, the shrines of Mecca and Medina were extensively restored. Major cities were endowed with commercial buildings, religious foundations, and bridges. In Cairo, the complex of Qa’itbay in the Northern Cemetery (1472–74) is the best known and admired structure of this period. Apart from his own patronage, Qa’itbay encouraged high-ranking officials and influential emirs to build as well. Building continued under the last Mamluk sultan, Qansuh al-Ghawri (r. 1501–17), who commissioned his own complex (1503–5); however, construction methods reflected the finances of the state. At this time, the Portuguese were gaining control of the Indian Ocean and barring the Mamluks from trade, their richest source of revenue. Though the Mamluk realm was soon incorporated into the Ottoman Empire (1517), Mamluk visual culture continued to inspire Ottoman and other Islamic artistic traditions.” What are the main points of the passage? 12345678910-